[Ausgeprägte Magen-Dilatation durch Essattacke erfordert chirurgische Intervention: eine Fallbeschreibung]

Johannes Lemke 1Jan Scheele 1

Stefan Schmidt 2

Mathias Wittau 1

Doris Henne-Bruns 1

1 Clinic of General and Visceral Surgery, University of Ulm, Germany

2 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University of Ulm, Germany

Zusammenfassung

Das akute Abdomen ist ein Krankheitsbild, welches regelmäßig in der Notfallmedizin anzutreffen ist. In den meisten Fällen sind intra-abdominelle Pathologien ursächlich, jedoch können sich auch extra-abdominelle Krankheiten als akutes Abdomen manifestieren oder dieses hervorrufen. Da das akute Abdomen immer potentiell lebensbedrohlich ist, ist das sofortige Handeln von großer Wichtigkeit. Hier berichten wir von einer jungen Frau, die sich mit dem Bild eines akuten Abdomens in unserer Klinik vorstellte. Die Bildgebung zeigte einen massiv dilatierten Magen, der bis in das kleine Becken reichten. Die Ursache hierfür blieb zunächst unklar. Notfallmäßig erfolgte eine explorative Laparotomie, in der über eine Gastrotomie große Mengen verbackener, unverdauter Speisereste geborgen wurden. Postoperativ konnte in der Anamnese durch einen hinzugezogenen Psychiater eine Essstörung mit täglichen Essattacken als Ursache für den massiv dilatierten Magen diagnostiziert werden. Die Patientin erholte sich schnell von dem Eingriff und konnte in gutem Allgemeinzustand und mit einer psychiatrischen Weiterbetreuung entlassen werden. Dieser ungewöhnliche Fall zeigt, wie eine psychiatrische Grunderkrankung ein akutes Abdomen verursachen kann. Weiter macht es deutlich, dass ein schnelles Handeln für die richtige Diagnosestellung und adäquate Therapie von Wichtigkeit ist, um Komplikation zu vermeiden und eine vollständige Genesung zu ermöglichen.

Schlüsselwörter

Chirurgie, akutes Abdomen, Essstörung, Essattacken, Magen-Dilatation

Introduction

The acute abdomen is a clinical picture which is commonly encountered in emergency units [1]. It is characterized by acute and mostly intense abdominal pain accompanied by peritonism and potentially meteorism, nausea, vomiting and in severe and advanced cases shock. In most cases abdominal pathologies cause this acute condition including – but not limited to – appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, mesenteric ischemia, ileus and perforations of hollow organs [2], [3]. However, also extra-abdominal diseases can present with symptoms of an acute abdomen such as testicular torsion, myocardial infarction or diabetic ketoacidosis [4]. Due to the fact that an acute abdomen is always potentially life-threatening, prompt action is required to obtain the diagnosis and to immediately initiate adequate therapy [5]. Diagnostically, in addition to clinical examination and analysis of serum parameters, imaging such as sonography, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are foremost in leading to the correct diagnosis [6]. However, as mentioned above, the causes for acute abdominal symptoms are versatile and at times are found in medical areas other than gastroenterology itself. In this study we report on an interesting and unique case in which a psychiatric condition was the underlying disease leading to an acute abdominal picture which required immediate surgical intervention.

Case description

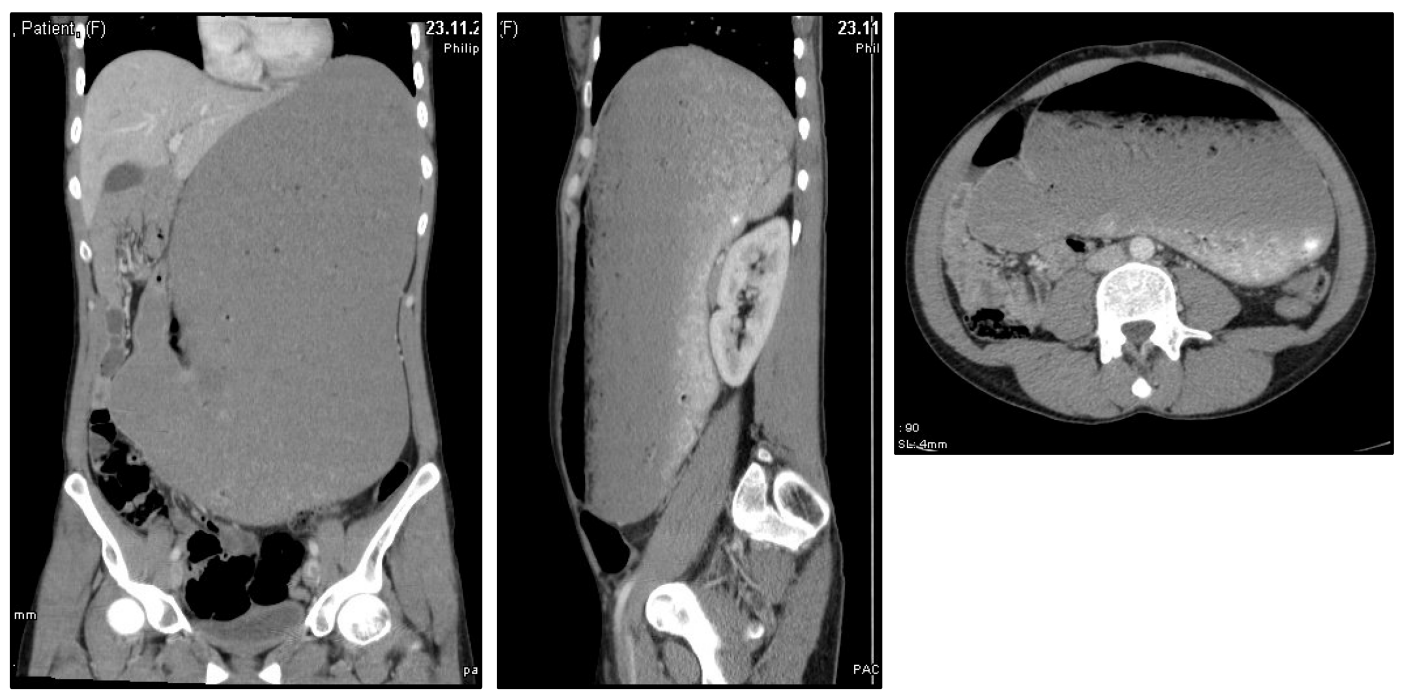

A 28-year-old woman presented in our surgical emergency unit with a sudden onset of progressive abdominal discomfort and pain. Anamnestically, the patient denied any preexisting conditions or previously performed surgeries. The patient was not under any long-term medication. Physical examination revealed a distended and meteoritic abdomen with signs of peritonism. Routine laboratory analysis did not show any pathologies, including normal hemoglobin, leucocytes, C-reactive protein (CRP) as well as serum electrolytes. Because of the acute and dramatic clinical presentation we immediately performed a computed tomography of the abdomen. This revealed a massively distended stomach with a cranio-caudal extension of 35 cm reaching the lesser pelvis, however, without evidence for perforation (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). Initially, the cause for the distention remained elusive. The patients was admitted to our intensive care unit. A stomach tube was placed, which, however, did not drain any significant amount of stomach content. We therefore decided on an emergency explorative laparotomy on the same day. Intraoperatively, in addition to the massively dilatated stomach no abnormalities were detected. We performed a gastrotomy of the gastric antrum and recovered (over the period of one hour) a large amount of cementitiously clotted and undigested food scraps from the stomach. Subsequently, the stomach was closed by sutures and an intraabdominal drainage was placed. An intraoperative performed gastroscopy did not reveal any stenosis or other pathologies. The postoperative course was without complication. The stomach tube as well as the intrabdominal drainage could be removed within the first days after surgery. A gradual reintroduction of liquids was well tolerated. On the sixth postoperative day we performed a radiological imaging of the stomach using contrast medium which revealed a re-tonised stomach of a normal size without evidence for any stenosis (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]). Subsequently, the patient was allowed to normal food intake, which was well tolerated as well. The postoperatively initiated evaluation of the patient by a psychiatrist revealed that she had been suffering from an eating disorder since her childhood. This was initially characterized by an anorectic behavior with starvation und excessive exercising. Temporarily, her body mass index (BMI) had dropped to 11 kg/m². At consultation in our clinic her BMI was in the lower normal range. However, the patient reported on daily binge eatings caused by conflicts at her workplace. This had also occurred on the day of hospital admission, however on this day, the routinely self-induced vomiting after the binge attack failed. In a good status of health the patient could be dismissed from our clinic on the 13th postoperative day. The psychiatric co-treatment therapy was continued.

Figure 1: Computed tomography of the abdomen revealing a massively distended stomach Upon admission of the young woman presenting with the clinical picture of an acute abdomen, we performed a computed tomography of the abdomen. This revealed a massively distended stomach reaching the lesser pelvis.

Figure 2: Postoperative imaging of the gastro-intestinal passage Postoperatively, we performed an X-ray series of the stomach upon application of contrast medium. This revealed a re-tonised, normal-sized stomach without evidence for stenosis.

Discussion

Here, we report on an unusual case in which a binge attack in a young woman suffering from an eating disorder caused a massive dilatation of her stomach. This dilation was not reversible either by self-induced vomiting or by drainage using a stomach tube. Therefore, immediate surgical treatment was required. Some other authors have reported on cases in which eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa lead to acute gastric dilatation [7], [8], [9], [10]. In line with the higher incidence of eating disorder in young females, mostly women in the age between 14 and 30 years were affected. In some cases, the so-called superior mesenteric artery syndrome has been suggested to cause or at least promote gastric dilatation in patients with eating disorders [10], [11]. For this syndrome it has been proposed that malnutrition leads to the shrinkage of a fad pad localized between the aorta and outlet of the superior mesenteric artery. This, in turn, may cause compression of the duodenum thereby promoting gastric dilatation, in particular in cases when eating binges occur. In the reported case of this study, immediate imaging revealed the diagnosis and emergency explorative laparotomy and gastrotomy allowed for full recovery of the patient without complications or any residuals. This prompt and direct action including emergency laparotomy appears to be justified and essential, given the fact that some authors have reported severe complications such as gastric perforation and/or necrosis in patients with similar conditions [10], [12]. Furthermore, in some cases extended surgical approaches such as partial gastrectomy or even gastric resection were required. The fact that some patients did not recover and, unfortunately, passed away, confirms the severity of this condition as well as the importance of adequate diagnosis and immediate (surgical) therapy.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Kamin RA, Nowicki TA, Courtney DS, Powers RD. Pearls and pitfalls in the emergency department evaluation of abdominal pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003 Feb;21(1):61-72, vi.[2] Miettinen P, Pasanen P, Lahtinen J, Alhava E. Acute abdominal pain in adults. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1996;85(1):5-9.

[3] de Dombal FT. The OMGE acute abdominal pain survey. Progress report, 1986. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;144:35-42.

[4] Tsipouras S. Nonabdominal causes of abdominal pain--finding your heart in your stomach!. Aust Fam Physician. 2008 Aug;37(8):620-3.

[5] Trentzsch H, Werner J, Jauch KW. Der akute Abdominalschmerz in der Notfallambulanz - ein klinischer Algorithmus für den erwachsenen Patienten [Acute abdominal pain in the emergency department - a clinical algorithm for adult patients]. Zentralbl Chir. 2011 Apr;136(2):118-28. DOI: 10.1055/s-0031-1271415

[6] Stoker J, van Randen A, Laméris W, Boermeester MA. Imaging patients with acute abdominal pain. Radiology. 2009 Oct;253(1):31-46. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.253109030

[7] Saul SH, Dekker A, Watson CG. Acute gastric dilatation with infarction and perforation. Report of fatal outcome in patient with anorexia nervosa. Gut. 1981 Nov;22(11):978-83. DOI: 10.1136/gut.22.11.978

[8] Repessé X, Bodson L, Au SM, Charron C, Vieillard-Baron A. Gastric dilatation and circulatory collapse due to eating disorder. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Mar;31(3):633.e3-4. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.10.018

[9] Tweed-Kent AM, Fagenholz PJ, Alam HB. Acute gastric dilatation in a patient with anorexia nervosa binge/purge subtype. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010 Oct;3(4):403-5. DOI: 10.4103/0974-2700.70774

[10] Adson DE, Mitchell JE, Trenkner SW. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome and acute gastric dilatation in eating disorders: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1997 Mar;21(2):103-14.

[11] Welsch T, Büchler MW, Kienle P. Recalling superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Dig Surg. 2007;24(3):149-56. DOI: 10.1159/000102097

[12] Arie E, Uri G, Bickel A. Acute gastric dilatation, necrosis and perforation complicating restrictive-type anorexia nervosa. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 May;12(5):985-7. DOI: 10.1007/s11605-007-0414-6