Dance movement therapy and dance interventions for people living with dementia: a PRISMA scoping review on health and well-being outcomes, assessments, and interventions

Clara Cornaro 1,2Sabine C. Koch 1,2,3

1 Department of Creative Arts Therapies and Therapy Sciences, Research Institute for Creative Arts Therapies (RIArT), Alanus University, Alfter/Bonn, Germany

2 School of Therapy Sciences, SRH University Heidelberg, Germany

3 Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, University of Melbourne, Australia

Abstract

Background: Living with dementia is an increasing reality for many people and their caregivers in our ageing society. There is a growing interest to employ dance movement therapy (DMT) and dance interventions as non-verbal, embodied approaches to engage people with dementia and reduce their symptoms. However, the outcomes measured in different studies vary greatly depending on whether the approach is oriented toward a biomedical perspective focused on reducing diagnostic symptoms or on a person-centered care approach, focused on maintaining personhood.

Methods: To better understand the health and well-being outcomes of DMT/dance interventions for older adults living with dementia, we conducted a scoping review. The databases Google Scholar, PubMed, PsycInfo, PubPsych, and LIVIVO were systematically searched for studies published between 2000 and 2021 addressing the health and well-being of older adults (65+) living with dementia via DMT/dance interventions. The data regarding participants, study design, aim/purpose, intervention frequency, type and duration, outcomes measured, findings and effect were charted and organized according to two outcome frameworks: the International Classification of Functionality, Disability and Health (ICF) and the Dunphy Outcomes Framework (DOF), an outcome framework for DMT. The data synthesis focused on outcomes, assessment tools, and intervention type, as closely interlinked entities. A critical appraisal of the results was undertaken.

Results: The Nstudies=26 studies included reflected a wide range of outcomes. Using the DOF for synthesis, we found that the physical domain was studied most frequently, closely followed by the emotional and cognitive domain. This was followed by the integration, cultural and social domain respectively. Synthesized via the ICF, the outcomes were formulated at all levels: Body Functions and Structures, Activity and Participation, Environmental as well as overarching Quality of Life. All studies reported a positive effect in the outcomes measured, four studies measured no effect, and one study a negative effect. There has been an increase of research in the field and while the overall quality of studies remains low a recent RCT and mixed-method study show an improvement.

Conclusion: As multi-modal interventions, DMT and dance interventions address numerous symptoms of dementia. The two frameworks applied can serve as an orientation for practitioners, and as a point of departure for further interdisciplinary research and policy development. Both frameworks, through the integration of different perspectives, allow for an integrative intervention plan.

1 Introduction

1.1 Rationale

Living with dementia is an increasing reality for many people and their caretakers in our ageing society. Impairment in cognitive functioning such as memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language and judgment are key symptoms of Dementia. The International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) continues to describe that cognitive impairment is ‘commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behavior, or motivation’ [1]. In the clinical setting, these non-cognitive and non-neurological symptoms of dementia are often comprised in the term Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD), occurring in most patients with dementia, with agitation, depression, apathy, and anxiety being the most frequent forms [2]. BPSD lead to greater functional impairment, resulting in early long-term care [3]. There is currently no treatment to the etiologies although there has been an improvement to alleviating and slowing down the non-cognitive symptoms [4]. In an increased financial, political, and research effort to relieve the symptoms of dementia, there is an emphasis on non-pharmacological treatment methods [5], [6]. These are less likely to have side effects, which are a considerable drawback in pharmacological treatment approaches [7], [8], [9], [10].

Dance and dementia

Dance has various promising interfaces with the needs of persons with dementia. Research shows that dance is an effective physical activity especially targeting functioning fitness [11]. This aspect addresses the cardiovascular and muscle activation achieved through dance that supports fitness, strength, and flexibility, needed to complete daily functions such as climbing stairs, walking, or washing. There is increasing interest and research in neuroscience and philosophy in the concept of embodied cognition, which recognizes that the body is not only connected to but influences the mind [12], [13]. While the symptoms of dementia are understood as cerebral dysfunctions [1], this concept suggests that activation in the body does not only contribute to functioning fitness but also to cognitive functioning. One example of this is that dance has been found to increase neuroplasticity [14]. Neuroplasticity describes the capacity of the neural networks in the brain to change through growth or reorganization, which impacts learning and memory.

Kontos and Grigorovich [15] are wary of the increased interest in embodied cognition and its effects on how dance is understood, with the concern that dance is reduced to a cognitive process, and the body is left behind. They argue that “…this approach fails to accommodate the very premise of the origin of somatic knowledge: a pre-reflective notion of agency that incorporates, rather than isolates, embodied intelligibility. It is our argument that somatic knowledge is what should be granted primacy in efforts to understand how people with dementia engage with dance” ([16], p. 167). Part of our somatic knowledge activated through dance is our embodied memory. Various research shows that the embodied memory of people with dementia stays intact until very late, even offering learning opportunities [17], [18], [19].

While body memory remains rich and intact, the verbal form of inter-personal communication becomes increasingly difficult. In his PhD thesis, the dance movement psychotherapist Richard Coaten shows how dance movement therapy can be a powerful way of building bridges [20] for people with dementia and those around them as it draws on body memory and facilitates non-verbal communication. Kinaesthetic empathy, which facilitates connection on an embodied level is fundamental for nonverbal relating [21], [22], [23], [24]. The dance movement therapists Newman-Bluenstein and Chang [25] have developed a manual to build bridges, particularly between people with dementia and their caretakers. Facilitating ways of connecting addresses several of Kitwood’s (1997) primary psychological needs of people with dementia (love, inclusion, occupation, attachment, comfort, and identity) [26]. Connecting in these ways has the potential to reduce sentiments of misunderstanding and neglect that foster the BPSD symptoms of aggression, anxiety, and depression. Rather than highlighting the decline of function through symptoms, focusing on embodied opportunities activates resources and strengthens the sense of self.

Resource activation is one of the key therapeutic factors of dance movement therapy (DMT) [27], [28], [29]. DMT, defined by the European Association of Dance Movement Therapy (EADTA, 2021), is “the therapeutic use of movement to further the emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual and social integration of the individual” [30]. The focus of this definition is on the integration and transformation – aiming for a change on various levels of the person. This holistic perspective is in line with the person-centered care approach in dementia literature, which points to the importance of addressing the person as a whole and maintaining personhood even as a person’s daily functioning may decline [26].

The multimodal strengths of dance have also been operationalized in various dance interventions to target the diagnostic symptoms of people living with dementia. Here, the focus lies on the aerobic, cognitive, and motor activation via dance rather than on facilitating psychological processes. The social aspects of being part of a group and music are encouraged to increase motivation and participation [11], [31]. Different dance forms, such as salsa, tango, or waltz, are often adapted to the clients’ needs and targeted outcomes.

Music, as a fundamental aspect of dance, plays an important role with people with dementia [32], [33]. It provides a common soundscape and allows synchrony via a shared rhythm. Participants with severe dementia often retain the memory of songs from their child or young adult times facilitating moments of singing, remembering and being part of a group. Synchrony, remembering, interaction along with embodiment are some of the relevant therapeutic factors of the creative arts therapies found in a recent scoping review by de Witte and colleagues [34].

Past reviews on dance and dementia

The range of opportunities for dance and dementia is also reflected in past studies’ wide range of outcomes. A systematic review by Mabire and colleagues [35] analyzes dance interventions for people with dementia and identifies recommendations for the developments and the implementation of these interventions. The review includes 14 studies, and comments on the lack of quality of these. Reasons mentioned for low quality of research include limited reporting of treatment indications, study design, type of experimental dance, sampling characteristic and dosage of intervention. Under “experimented dance interventions” it includes a range of intervention types among them dance movement therapy. As part of the review summary, the authors observed four categories of processes in the studies: physical, cognitive, psychological, and social.

Specific to dance movement therapy, no study met the inclusion criteria of the 2017 Cochrane review by Karkou and Meekums [36] assessing the effectiveness of DMT for dementia. The recently (2023) updated version of the review [37] includes the study by Ho et al. [38] which is also part of this review. There have been two systematic reviews on DMT and dementia by Lyons et al. [39] and Jiménez et al. [40] that have a less stringent inclusion of study designs (study search completed in 2018). The former included adults aged 65+ with dementia in their search. While the intention of the latter review was to include adults aged (60+) living with a mental health disorder more broadly, of the 16 studies included, 15 dealt with dementia, and one with depression. The reviews summarize various positive findings in descriptive form that range from communication, strengthening relationships, coordination, concentration, rediscovering identity, experiencing significant moments, improved quality of life, and improving physical and cognitive functions. Both reviews comment on the lack of quality of the research, resulting in a recommendation to refrain from speaking of DMT efficacy for people with dementia for now. Lyons et al. [39] mention that there seems to be a lack of consensus regarding outcome measures as a limitation of their review. Jiménez et al. [40] encourage the reader to think of solutions to challenges in initiating further research in the field, suggesting to build international teams of DMT and researchers of related fields to collaborate and improve the studies’ quality.

This review

The aim of this scoping review is to provide a clear overview of outcomes currently addressed via DMT and dance interventions, to inform further inter-disciplinary research. Outcomes are understood as “the consequences directly attributable, at least in part, to the program or project and are usually measured at, or shortly after, completion” [41]. A recent scoping review of outcomes measured for non-pharmacological interventions for people with dementia [42] has found a lack of consistency of outcomes. The inconsistency reflects the various objectives informing outcomes shaped by various ways of understanding dementia care. The types of interventions offered for people with dementia and the ways of measuring outcomes reflect this variety. Hence, this scoping review takes a step back to get an overview of outcomes measured, to make an informed step forward with further research.

While the research for DMT/dance interventions for people with dementia is becoming more promising, an overview of the outcomes is lacking, making it challenging to coordinate and synthesize research or orientate practitioners. The authors chose the method of a scoping review to be as inclusive as possible in the study selection in order to gain a broad overview. Furthermore, the aim of the review is to map what outcomes have been assessed, rather than make a recommendation on the effectiveness of DMT/dance to address these [43]. The process follows the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [44].

1.2 Research question and objectives

The primary research question for this scoping review was: what health and well-being effects (outcomes) do DMT/dance interventions (intervention) have for older adults (65+) living with dementia (participants)? The main objective is to establish a comprehensive list of outcomes that match an accessible and relevant framework to know what goals can be targeted, find a common language, and encourage research projects. To gain a more in depth understanding of the outcomes measured, the secondary objective of this review, is to gain an overview of the tools used to measure the outcomes. In a similar vein, the third objective aims to list the interventions applied to reach these.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol and registration

Because scoping reviews are not eligible for a registration via PORSPERO, there was no registered protocol.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

The eligibility characteristics were persons living with dementia over 65 years (participant), partaking in dance movement therapy/dance interventions (intervention) measuring health/well-being related outcomes (outcomes). The PICOS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study design) was used to refine inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2.1 Population

Studies were excluded if the participants were not diagnosed with dementia or were not above 65 years on average. Research concerning people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was excluded, as it is not a diagnosis of dementia but signals a likelihood of its development.

2.2.2 Interventions

In line with the objective of this review, the inclusion criteria regarding the intervention was defined as the therapeutic use of dance movement to promote a patient’s health and well-being. No special training or qualification of the facilitator was taken into consideration here. Studies were excluded if there was no therapeutic adaptation of the dance method – for example social dancing, that is the dance intervention needed to have a stated therapeutic purpose.

2.2.3 Comparators

A comparison/control group was not required.

2.2.4 Outcomes

The outcome measured had to be health or well-being related, i.e., studies measuring attendance or satisfaction with the intervention were excluded.

2.2.5 Study designs

To include a wide range of research designs, both qualitative and quantitative, and arts-based studies were included. The inclusion criteria required an empirical approach. Hence, systematic reviews, expert opinion, and planned studies were excluded, and all settings were accepted.

2.3 Information sources

To locate relevant studies, the following electronic databases were searched from 2000 to April 2021 (lastly 13 April 2021): Google Scholar, PubMed, PubPsych, PsycInfo and LIVIVO. Furthermore, the electronic database search was supplemented by screening relevant systematic reviews [35], [36], [39], [40]. In addition, the author contacted leading researchers in the field and international mailing lists of dance movement therapy (EADT, ADTA) to ask for ongoing research in the field (none reported). Finally, the reference management tool EndNote 20 was used to manage the retrieved results.

2.4 Search

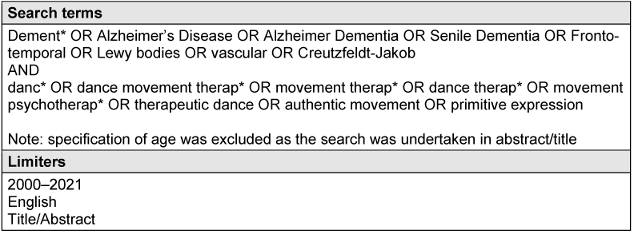

The first author (CC) developed and executed the search strategy. The search strategy was revised by an experienced librarian of SRH University. Table 1 [Tab. 1] shows the final search terms and limiters.

Table 1: Overview of search terms and limiters

2.5 Selection of sources of evidence

At first, all duplicates were removed (using the automatic EndNote function). Then the articles were screened at the title/abstract level to see if they match the population, intervention, outcome, and study design (see PICOS eligibility criteria above). The remaining articles were screened at full-text length to make the selection. The first author (CC) was primarily responsible for the selection process. Uncertainties around five articles were clarified with the second author (SK). The first author shared her PICOS framework and the articles with the second author, withholding her own opinion. The eligibility was then discussed, and reasons for the decision were recorded. There were no disagreements that required a third party. 5.1 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] shows the decision process that led to the exclusion of the study by Chita et al. [45]. In the process, the initially selected time frame ‘since 1990’ was reduced to ‘since 2000’ to focus towards the more recent ones (this resulted in the removal of three studies: [46], [47], [48]).

2.6 Data charting process

A data-charting table was created by the author using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) template retrieving general information from the selected studies. The final data selected for charting drew on past scoping reviews, systematic reviews, and data relevant to the author’s research question. The first step was to chart general data (see 2.7 Data items) from the studies in a table. More detailed data regarding outcomes, assessment tools and interventions was charted as a second step and used to double-check the information gathered in the general table by going back to the original articles to reveal potential errors.

To chart the outcomes measured, the full texts were screened, and outcomes were listed in a table as appearing in the text. Formulations were recorded as in the text, only using an already listed outcome if it matched exactly. For example, “well-being” and “psychosocial well-being” were recorded separately to take these nuances into account. This was double-checked in the process of charting tools used to assess outcomes.

2.7 Extraction categories (data items)

The extracted data included 1. article characteristics (author, country, and date), 2. participant characteristics (diagnosis, age, sex), 3. setting (e.g., at-home, inpatient center), 4. study design (e.g., qualitative, mixed-methods, RCT), 5. aim and purpose of the study (e.g., test the efficacy of a therapeutic tango intervention), 6. type, frequency, and duration of therapy (e.g., 30 min/week for six weeks, DMT), 7. outcomes measured (e.g., depression, agitation), 8. method of data collection and times (interview pre- and post-intervention), 9. data analyses (e.g., emerged themes matched with Quality-of-Life components), 10. findings (e.g., intervention increased well-being with no results on gait and balance). The setting and data analysis was later removed, and effect and bias were added, as it was more relevant for the research question. The more detailed extraction regarding outcomes, assessment tools and interventions were also charted separately via the process described above (2.6 Data charting process). The terms used were kept as close to the original as possible.

2.8 Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence

For inclusion in this scoping review, the research quality was not considered, as the aim was to obtain a broad overview of the health and well-being effect of dance interventions/DMT for older adults with dementia. However, the selected studies were critically appraised for the reader to judge the results accordingly and to serve as a quality orientation for future studies in the field. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) developed the critical appraisal tools used. These were chosen as they address internal validity and reliability of the studies in the form of an elaborated checklist. The first author selected the appropriate checklist for each study according to study design (qualitative [49], quasi-experimental [50] or randomized controlled trials [50]) and completed by the author individually. For specific concerns and questions, the second author was referred to for advice. To compensate for the lack of a further reviewer, the first author established clear criteria for how she completed the review, firstly, by setting up more detailed criteria for answering the checklist (e.g., what defines as ‘adequate’), secondly, by recording the reason for her decision for each point answered. These processes are included as supplements for transparency (Attachment 1 [Att. 1], 5.2). The authors encourage the reader to refer to this content when drawing information from the critical appraisal.

All checklists had the following four options: Yes, No, Unclear or Not applicable. The qualitative checklist consisted of 10 items, the quasi-experimental checklist of 9 items and the randomized controlled studies checklist of 13 items. For studies that used a mixed-methods design, one qualitative and quasi-experimental checklist was completed, and hence two scores were given. The qualitative aspect was not considered for one mixed-methods study, as it did not match the research question (the study [51] measured the effect of the intervention on agitation, and the qualitative part asked employees and participants regarding their satisfaction with the program). The results from the critical appraisal are elaborated under point 3.3 in the results section.

2.9 Synthesis of results

Due to the heterogeneity of the outcomes, two frameworks were selected that encompass all outcomes to provide an overview.

2.9.1 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [52] was established by the World Health Organization (WHO) and approved in 2001. This framework was selected as it includes outcomes on different scales (from a functional body level to a societal-contextual level), drawing on a bio-psycho-social model of health. It is an addition to the ICD [1]. While it is used in combination, it takes an independent stance from etiology. This separation is reflected in the change from the previous name ‘Illness consequences’ to the current name ‘components of health’. The goals of the ICF are various: first, to serve as a scientific basis for the understanding and studying health status and related states, the results, and the determinants; second, to provide a common language for describing health status, improve communication between various users, experts in health institutions, researchers, politicians, and the public, including people with disabilities; third, to facilitate data comparison between countries, disciplines, health services and over time; lastly, to offer a systematic coding system for health information systems [52]. As the interventions included in this scoping review are from different disciplines, this framework serves as an overarching tool that provides a common language.

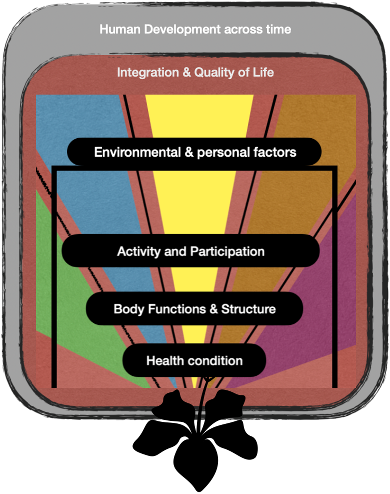

Fig. 2 in [53] describes the framework. The ICD is used to define the ‘Health Condition’; the ICF describes the other parts. Body Functions & Structure and Activity & Participation describe the functional level of the person. Environmental and Personal Factors describe the contextual factors. These components are further divided into sub-categories. In this article, we draw on the extended ICF version which also includes the incorporation of quality of life (QoL) and well-being. In 2010, McDougall et al. have published a modified version with a diagram of the framework that includes QoL (Fig. 2 in [53]). The rest of the article draws on this modified version of the ICF framework, including QoL as an encompassing domain, as it is such a crucial outcome for this population.

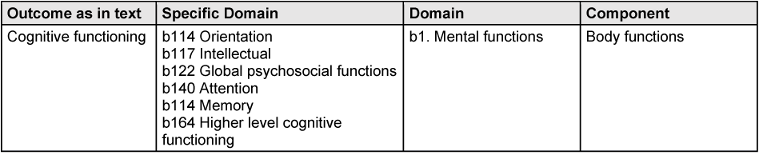

The first author matched the studied outcomes to the sub-categories of the ICF and recorded these along with the appropriate components (see 5.3 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] for this process). For example, ‘cognitive functioning’ was frequently measured; this outcome consists of various aspects (e.g., memory, orientation). This matches with various sub-categories (e.g., memory, attention), which are part of the ‘mental functions’ domain organized within the ‘body functions’ component (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]). The overarching component ‘body functions’ has the code ‘b’. ‘Mental functions’ is the first domain within this component; hence it is coded as ‘b1’. Each increasing degree of specificity adds another number behind b1.

Table 2: Matching outcomes to the ICF: an example using the outcome ‘cognitive functioning’

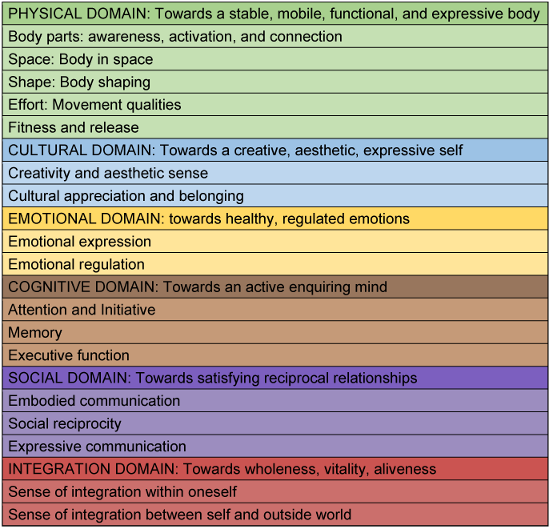

2.9.2 Dunphy Outcome Framework (DOF)

The second framework used, the Dunphy Outcome Framework (DOF), was recently established for DMT by Dunphy et al. [41]. It takes a holistic approach and consists of a physical, cultural, cognitive, emotional, social and integration domain (see Table 3 [Tab. 3]). These domains derive from Hanna’s [54] universal descriptors of learning through dance [41]. Therefore, while it is an outcome framework established for DMT, it has its roots in common factors of dance, which is why it is also chosen to represent other dance interventions. While the tool is designed for DMT, the developers state that it may also be relevant for other therapeutic modalities, particular other CATs [55], [56]. It has, for example, been tested on a small scale with psychomotor therapists [57], with findings indicating that it helped develop a group profile and set objectives. Some of the dance interventions included in this review are based on psychomotor theory.

Table 3: The Dunphy Outcome Framework for Dance Movement Therapy ([41], p. 4)

The framework has been validated with the practice knowledge of more than 100 DMT practitioners worldwide (including Australia, Canada, China, Germany, Holland, Italy, Korea, New Zealand, Portugal, Switzerland, Taiwan, and the USA) ([41], p. 6). The Outcomes Framework is devised to be used for diagnosis, formative, and summative assessment. It addresses the lack of consistency for agreed outcomes and associated measures within the DMT profession [58]. In a recent analysis the DOF scored high in reliability and validity [59].

The six main domains of the framework (physical, cultural, emotional, cognitive, social, and integration) are based on a holistic approach to well-being. They are ordered according to their significance for DMT practice, the physical domain listed first. While they are separated to facilitate assessment and planning, they are understood to be inter-related and intrinsically connected [41]. The main domains further consist of sub-domains (see Table 3 [Tab. 3]). The sub-domains consist of another layer of description – for example, the subdomain 1.1 Body parts consists of 1.1.1 Use of breath to support the movement. The developers of the DOF recognize that it is primarily the physical domain whose sub-categories rely on the Laban Bartenieff Movement System (LBMS), which is specific to DMT. However, as this review uses the framework to organize outcomes in hindsight, it has not used the sub-categories, but only the main categories. Following the domains’ aim to suggest where the measured outcomes could fit regarding their focus. For example, the physical domain aims towards a stable, mobile, functional, and expressive body. Therefore, measured outcomes that support this aim (e.g., strength, balance, body awareness, physical well-being) were categorized within this domain.

2.9.3 Combination of frameworks

The author has chosen these two frameworks, as they help in the aim to understand what health and well-being outcomes dance movement therapy/dance interventions can have for older adults living with dementia. As an already established interdisciplinary tool, the ICF is used across all health professions, the public, researchers, and politicians. It provides various levels to assess a particular outcome (from body function to environmental components). This multi-level perspective is beneficial for working with people with dementia, as all components provide an opportunity for improvement. The DOF provides a tool that is DMT specific. Rather than having various levels, it provides a holistic map of possible outcomes understood as interrelated. Underpinned by a holistic approach to well-being, it supports the person-centered care perspective increasingly striven for in dementia care. Furthermore, the outcomes are strength-based and potential-focused, providing a resource-oriented perspective for people with dementia and their caretakers. Both frameworks manage to address diverse outcomes – whether they target function, emotional expression, or a relational dynamic.

The frameworks differ because the ICF is a classification system that helps answer where the outcome is classified. Whereas the DOF is meant to accompany therapeutic change and helps answer what domain the outcome supports. Therefore, an outcome supporting the emotional body according to the DOF can be situated in various components of the ICF. Likewise, an outcome located within the Body Functions component of the ICF can touch upon various aspects of self (cognitive, emotional, or physical). To summarize, the ICF helps to locate the level at which the outcome is formulated, while the DOF describes what domain of the body the outcome addresses.

3 Results

3.1 Selection of sources of evidence

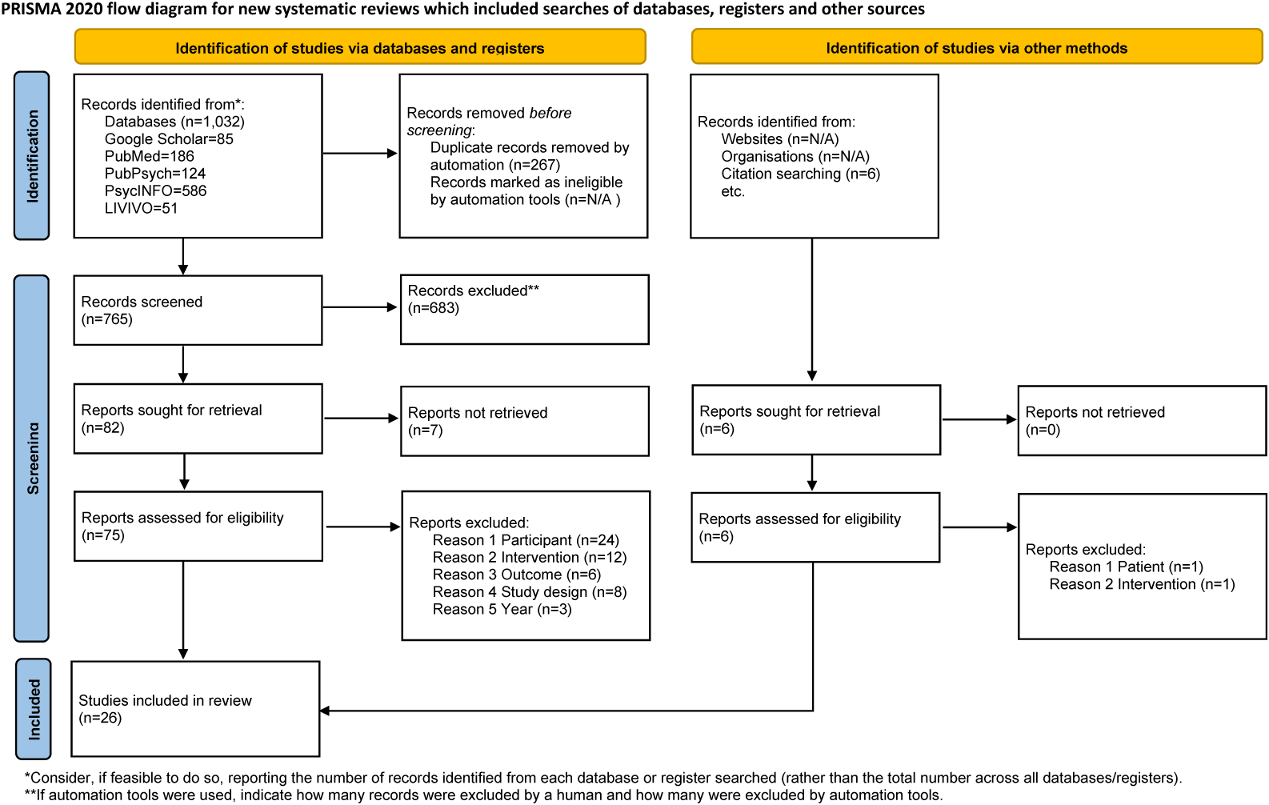

The database search resulted in 1,032 studies (Google Scholar=85, PubMed=186, PubPsych=124, PsycINFO=586, LIVIVO=51) of which 267 were removed as duplicates by the EndNote automated process. Seven hundred sixty-five studies were screened at the title and abstract level, of which 683 were excluded. Frequent reasons of exclusion were duplicates, irrelevant studies (e.g., biomedical drug studies or other creative therapies (music, art, drama), or reviews). Eighty-two texts were sought for retrieval at full-text length. Of these, seven could not be retrieved. Of the 75 studies assessed for eligibility, 53 were excluded based on participants (N=24), intervention (N=12), outcome (N=6), study design (N=8), year (N=3) – see Figure 1 [Fig. 1], PRISMA flow diagram. An example for exclusion based on the participant was the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which is a pre-stage to dementia. An example of exclusion based on intervention was social dancing without a therapeutic intention.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

Adapted from Page et al. [89], licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Studies that assessed the attendance or satisfaction of an intervention without clear health and well-being outcomes were excluded. Study designs were excluded if they were protocols, reviews, or expert opinions. The author identified six publications by citation searching, of which six were sought for retrieval and assessed for eligibility. Of these studies, one was excluded due to participant criteria and another due to the intervention criteria. The remaining four were included in the review, resulting in 26 studies reviewed in this scoping review. The first author did the screening and eligibility assessment, and uncertainties were discussed with the second author (see Methodology 2.5).

3.2 Characteristics of sources of evidence

Of the 26 studies included, nine were qualitative [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], seven were quasi-experimental [51], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], five used a mixed methods design [20], [75], [76], [77], [78], four were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [38], [79], [80], [81], and one was a case report [82]. Regarding the type of publication, there were 16 journal articles, five theses (M.A. and PhD), two project reports and one book chapter. Most studies were conducted in the U.K. [20], [62], [63], [64], [66], [71], [77], [78] and the USA [60], [67], [68], [69], [82]. Two studies were each conducted in Hong Kong [80], [83], Singapore [72], [74], and Finland [73], [81]. Since the year 2000, there were increasing publications, with eleven studies published since 2016. Most studies had a sample size of 10 or less (N=12). Three studies had sample sizes bigger than 40 (N=60, N=165, N=204).

Regarding gender, the ratio of female to male participants was 3:1, with quite a few studies not mentioning the sex. The mean age of participants was 80.3 years. In terms of diagnosis, Alzheimer’ dementia or dementia not further defined was most frequently reported. Vascular dementia was mentioned in four studies [63], [68], [78], [81], and a combination of vascular and Alzheimer’s in two [61], [63]. Fronto-temporal dementia and Parkinson’s dementia were each represented in one study [63]. The severity of dementia ranged from very mild to severe. 5.4 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] shows the results of individual sources of evidence (point 17 on PRISMA-ScR).

3.3 Critical appraisal within sources of evidence

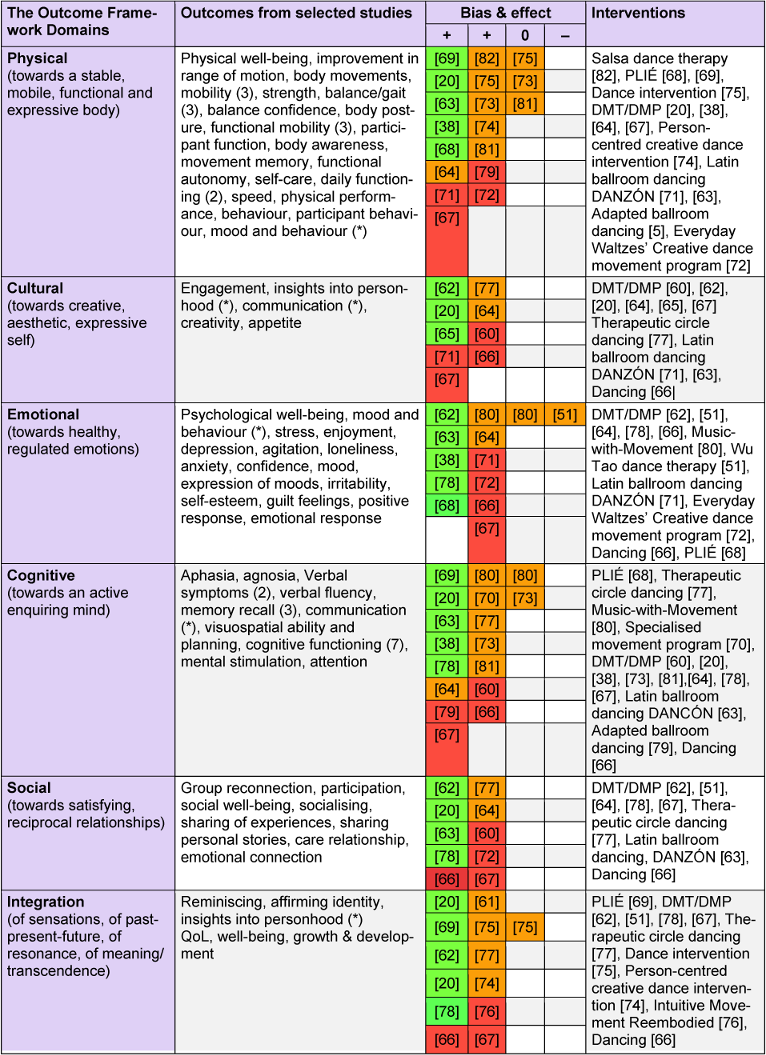

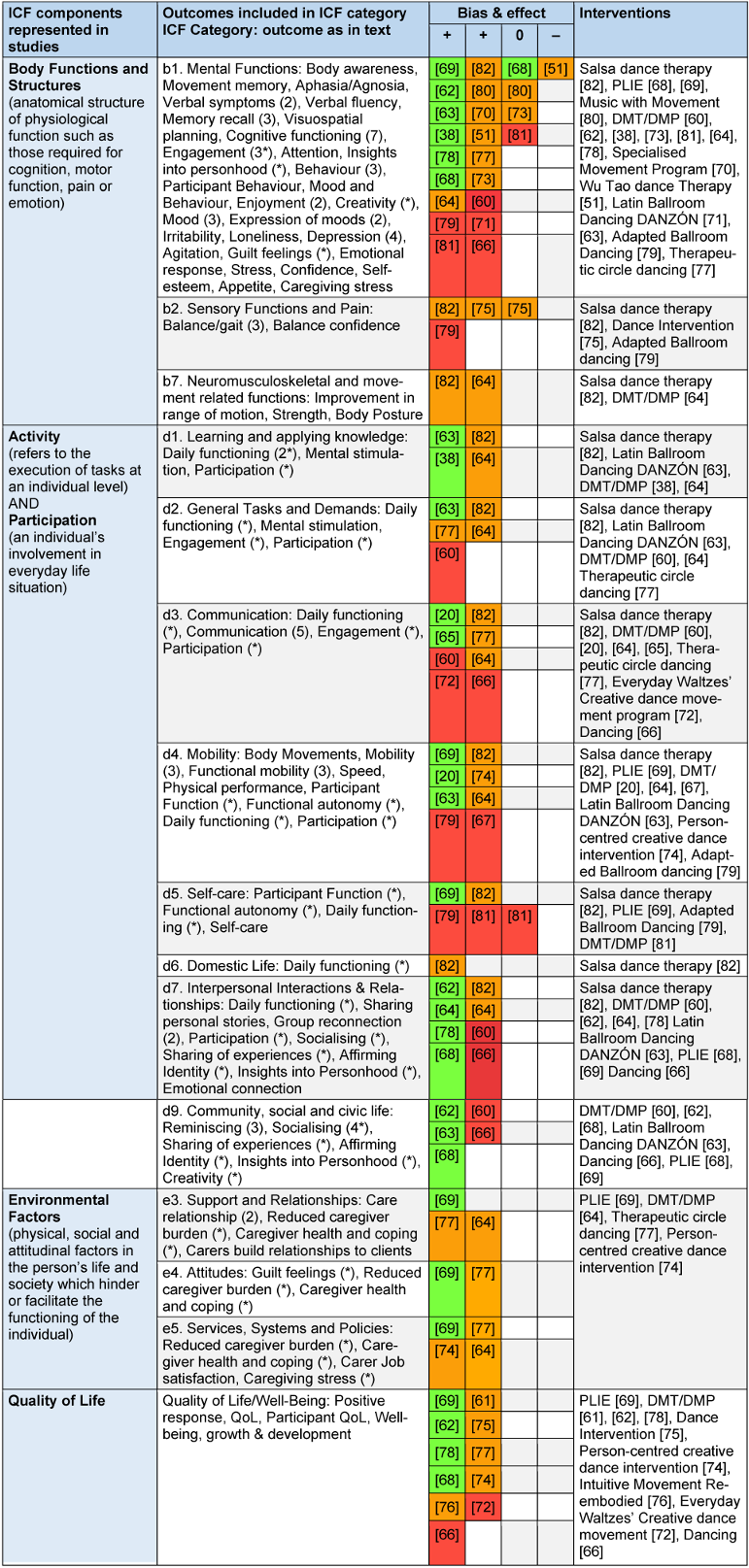

In line with previous reviews [35], [36], [39], [40], the overall quality of research in this field remains low – however, the recent RCT by Ho et al. [38] and the mixed-method study by Lyons [78], are an example of improved quality of recent studies. The detailed results of the critical appraisal rating can be found in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] (5.5). The overall rating of each study is visualized in the results tables Table 4 [Tab. 4] and Table 5 [Tab. 5].

Table 4: Results synthesized to DOF

Table 5: Results synthesized to ICF

3.3.1 Qualitative studies

Among the qualitative studies, the research by Coaten [20] and Lyons [78] had the highest score, with a 9 out of 10. Six out of 13 studies score more than half of the checklist with ‘yes’. Five studies score less than half of the checklist with ‘yes’. All studies received a ‘yes’ for points 8 ‘representation of participants and their voices’ and 10 ‘relationship of conclusion to analysis, interpretation of data’ of the checklist. This score suggests that participants are represented well across the studies, and conclusions drawn flow from the analysis or interpretation of the data. What was frequently unstated and hence marked as ‘unclear’ was the research methodology and the philosophical perspective. Likewise, the researchers are rarely culturally nor theoretically located. Neither was the researcher’s influence on the research and vice-versa stated. A reference to ethical procedures for the study was also frequently lacking.

3.3.2 Quasi-experimental studies

Among the quasi-experimental studies Barnes et al. [69], had the highest quality, scoring ‘yes’ in 8 out of 9 points on the checklist. In general, the quasi-experimental studies scored well on the clarity of the ‘cause’ and the ‘effect’ regarding the intervention and outcomes (point 1). However, whether participants included in any comparisons were receiving similar treatment/care other than the exposure or intervention of interest was often unclear, as was the reliability of outcomes measured. In addition, only two of the 11 studies had a control group.

3.3.3 RCTs

One of the critical quality markers of RCTs was the blinded study design. While so called ‘blinding’ was possible for some design steps, the participants generally cannot be blinded to treatment assignment, as this would ethically come into competition with informed consent and will most likely classify as less critical. Hence, this point was marked as ‘not applicable’ in all studies. In general, the RCT studies scored well on randomization used to allocate participants to treatment groups. What was frequently unclear, was whether the allocation to treatment groups was concealed, whether treatment groups were similar at baseline, and whether treatment groups were treated identically other than the intervention of interest. What was not included in any of the studies was the intention-to-treat analysis. Overall, Ho et al. [38] was the study that scored highest.

3.3.4 Case report

Lastly, the case report by Abreu et al. [82] fulfilled all the points on the checklist, demonstrating high quality.

3.4 Results of individual sources of evidence

Results of individual sources of evidence can be found as supplements in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] (5.5). Most of the studies found a positive effect, four studies found no effect in some of their outcomes measured, and one study found a negative effect.

3.5 Synthesis of results

In line with this review’s objectives, numerous results were synthesized in the following sections: outcomes, tools of assessment, and interventions.

3.5.1 Outcomes

There was a wide range of outcomes measured in the selected studies. These ranged from physical outcomes such as range of motion and mobility to more functional ones that assessed the capacity for daily functioning. These were closely related to those measuring cognitive functioning as they consider the capability to understand, evaluate and react to daily challenges. In addition to these individual capabilities, communication was another common outcome measured, considering the relational realm. Various moods and emotions were also assessed, such as irritability, loneliness, and stress (amongst others). Overarching outcomes that assess the well-being and quality of life of the participant were also frequent. As caretaking of people with dementia is a significant task, the outcome of the intervention on this task was assessed in various ways.

Results synthesized: the DOF

Table 4 [Tab. 4] synthesizes the results of the review from the perspective of the DOF. The table includes outcomes, effect, critical appraisal (C.A.), and intervention type. The outcomes are marked with a * if they are listed in more than one category. The physical domain aiming towards a stable, mobile, functional, and expressive body has been studied most, with six reliable studies. Eight of the 14 interventions included in this review addressed the physical body. Fifteen studies found a positive effect, whereas three of these also found no effect in some of the outcomes.

The cultural domain, aiming towards a creative, aesthetic, expressive self, has been addressed by four different intervention types. More than half of the DMT intervention studies have a focus here. Less than half of the studies included in the cultural domain score high on the critical appraisal. Twelve studies had researched the emotional domain, aiming towards healthy, regulated emotions, with five studies of high quality. Seven of the fourteen types of interventions chose to study this domain. Unfortunately, one study also found no effect, and one a negative one for some of its participants. The cognitive body, aiming towards an active enquiring mind, was included in fifteen out of the 26 studies, five of these of high quality. Nine of the 14 intervention types were mentioned in this category. The social domain was included in 10 studies, four of which were of high quality. Furthermore, four different intervention types focused on this domain, aiming towards satisfying reciprocal relationships. Lastly, the domain of wholeness, vitality, and aliveness, aiming towards an integrated self across domains, was assessed in eleven studies, four of high quality. It was a frequently targeted domain, as represented by nine intervention types.

Results synthesized: the ICF

Table 5 [Tab. 5] synthesizes the results from the perspective of the ICF. This table only includes ICF components that are reflected in the selected studies, therefore a component such as ‘Functions of the Skin and related Structures’ which was not targeted in any study was left out for a clearer overview. Within body functions and structures, not surprisingly, mental functions were studied most (in 18 of the 26 studies). All of them found a positive effect, four also found no effect, and one found a negative effect. Seven studies were of high quality, six of medium quality and five of low quality. Nine of the fourteen types of intervention were applied for this outcome. Less focus has been placed on sensory functions and pain and, neuro-muscular-skeletal and movement-related functions.

From a participation and activity perspective, most studies focused on the sub-components: communication, mobility, and interpersonal interactions and relationships (included in eight studies), each with a range of intervention types. Learning and applying knowledge, general tasks and demands, self-care and community, social and civic life are further sub-components that were focused on only been studied once by the intervention salsa dance therapy. As a case report, this study was present in almost all components due to its numerous measurements.

Environmental factors were also studied regarding support and relationships, attitudes and services, systems, and policies. The research quality here was high to medium, consistently with a positive effect.

However, only four of the 14 intervention types studied the environmental factors. Quality of life was studied in 11 of the 26 studies, with a positive effect, in more than four studies. The domestic life factor had a varying research quality. Seven of the intervention types were applied to assess this outcome.

3.5.2 Tools of assessment and outcomes

There was a broad range of tools used to assess outcomes in the selected studies. There was a lack of consistency of tools within the various DOF domains and ICF components. In accordance with the DOF physical, cognitive, and emotional domains had been measured the most frequent. These had been approached with qualitative and quantitative research methods. The social, cultural and integration domains had been studied almost entirely qualitatively. Common for qualitative studies were forms of observation, often coupled with video recording. The most frequent quantitative assessment tool was the Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-cog), both evaluating cognitive functioning. The time of measurement mostly includes baseline measurement, mid-point and at a time towards the end of the intervention. Only four studies [38], [71], [73], [80] had a follow up of longer than one week. A full list of method and time of measurement matched to framework can be found under point 5.6 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1].

3.5.3 Interventions and outcomes

The most represented intervention is DMT (in 40% of the studies). Across these, all outcome domains from the DOF and the ICF components are addressed. Looking at individual studies within the DMT intervention category, one focuses on the integration domain [61], two studied the physical and cognitive [73], and one addresses the cognitive and cultural domain [78]. The remaining seven studies include three or more domains [20], [22], [38], [60], [64], [67], [78]. In terms of the ICF framework, the DMT interventions address outcomes regarding body functions, activity/participation, environment, and QoL.

Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ) is a specifically established intervention incorporating various approaches and methodologies represented in two studies [68], [69]. According to the DOF, the intervention considers physical, emotional, and social outcomes. As with the DMT interventions, all ICF levels are addressed.

Two studies [63], [71] represent Latin ballroom dancing DANZÓN, which draws on a psychomotor therapy framework. The outcomes aim to address the physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development of the participants. Regarding the ICF framework, the intervention includes the components of body functions and activity/participation, but not from an environmental or QoL perspective.

According to the DOF, ‘Salsa dance therapy’ [69] addresses physical outcomes, which take a body function and an activity/participation perspective in the ICF. ‘Adapted ballroom dancing’ [79] targets the physical and cognitive domain and assesses these from a body function and activity/participation perspective. Study [75], applying ‘Dance intervention’ considers the physical domain situated in the body function component of the ICF. The ‘Music with Movement’ [80] intervention evaluates cognitive and emotional outcomes situated in the body function component of the ICF. ‘Intuitive movement reembodied’ [76] focuses exclusively on improving QoL, addressing the integration of body. The ‘Specialized Dance Program’ [70] targets cognitive outcomes situated at a body functional level. ‘Wu Tao dance therapy’ [51] focuses on the emotional domain, situated at the body functional level. ‘Everyday Waltzes creative movement program’ [72] looks at well-being overall and has divided this into physical, social, and psychological well-being. Hence in the DOF, it is categorized as considering the physical, social, and emotional self. In the ICF, this is part of the overarching component QoL. Study [77] applies the intervention ‘Therapeutic circle dancing’ and considers all outcome domains except for the physical. These are part of most ICF components, including QoL, excluding environmental. The ‘Person-centered creative dance’ intervention [74] looks at physical and integrational outcomes in all the ICF components, except the environmental factors. The intervention ‘dancing’ [66] aims at reaching cognitive, emotional, cultural, and integrational domains for a participant. In terms of the ICF, these outcomes are in the body functions, activity/participation and QoL component.

All interventions have a similar structure consisting of a warm-up, the main intervention, and closure. The main intervention is more structured and instructed in some studies, whereas other interventions are more loosely structured as they incorporate input from the participants. The number of domains considered in individual studies ranges from one to six. The more frequent targeted outcome domains from the DOF are physical, cognitive, emotional, and integrational. Less frequently included in the studies are the cultural and social domains. The DMT interventions, ‘therapeutic circle dancing’ [77] and ‘dancing’ [66], consider these two domains. In the ICF framework, the least frequent component addressed is the environmental one. DMT as well as PLIÉ [69], and the ‘person-centered creative dance intervention’ [74] evaluate the environmental factors.

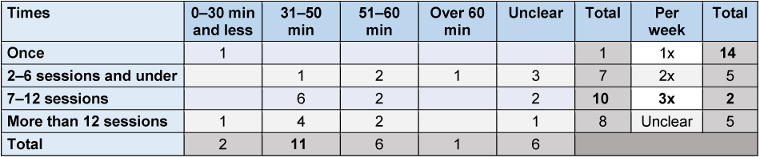

The intervention dose varied in time and frequency. Table 6 [Tab. 6] presents this range. Most interventions lasted between 30–50 min and took place once a week. The most common study duration was between 7 and 12 sessions (10 studies), with eight studies conducting more than 12 sessions.

Table 6: Dosage of intervention: frequency, duration, and overall number of sessions in study

Attachment 1 [Att. 1], 5.7, shows the results of interventions used in the selected studies. The table represents a brief description of the intervention, the study ID and the combined outcomes targeted. The outcomes of each study within the intervention are matched to the two frameworks for comparison. It is important to keep in mind that while the studies in this review address certain outcomes with certain interventions, this does not reflect the possibilities of the intervention as such, but rather with what intention it has been studied.

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of evidence

Twenty-six studies met the inclusion criteria of this scoping review. There has been an increase in research in the field, with eight studies published since the last reviews (since 2018 to April 2021). The studies included in this review show that DMT/dance interventions can have a wide range of effects for older adults with dementia. Most of the studies found a positive effect, one study found a negative effect on agitation [51]. The ratio of women to men included in the studies is 3:1. This may be due to the higher prevalence of dementia in woman (70%) [84], as well as dance potentially favored/associated with women, resulting in more women choosing or being allocated to interventions including dance.

The first objective of this scoping review asked what outcomes have been measured and what could be an overarching framework to map these? The ICF and the DOF were selected to map the outcomes measured across the studies selected. The kind of outcomes measured were various. Drawing on the DOF, most of these focus on the physical body supporting the person in changes in functional mobility, balance/gait, or self-care, to name just a few. The second most frequently addressed domain is the emotional body, including agitation, depression, mood, and irritability. Next, aspects such as memory recall, cognitive functioning, and verbal symptoms are considered part of the cognitive body, appearing in the third position of frequency. Following these domains is the integration domain which includes outcomes considering well-being and quality of life. Finally, less frequent but also addressed are the social and cultural domains, for which some outcome examples are socializing, creativity, and participation.

Organizing the outcomes measured in the selected studies into the ICF framework shows that dance movement therapy/dance interventions consider the person with dementia from various perspectives. Of these, body functions, the sub-category of mental functions appears most frequently. Mental functions include cognitive functioning, verbal symptoms, memory recall, loneliness, depression, and stress, i.e. Not represented in the selected studies is the ICF component body structure. The activity and participation components were frequently evaluated. The sub-categories here include communication, mobility, interpersonal interactions and relationships, community, social and civic life, i.e., considerable attention was also given to the ICF environmental component, considering contextual factors of health and well-being. Support and relationships, attitudes, services, systems, and policies, i.e., are sub-categories of this component. This review refers to the modified version of the ICF by McDougall et al. [53], as it includes quality of life as an overarching aspect to be considered, and this was an outcome evaluated by numerous studies (10 out of 25).

Especially the two outcome tables (Table 4 [Tab. 4] and Table 5 [Tab. 5]) synthesizing the results to the two frameworks show a comprehensive list of outcomes that helps to know which outcomes can be assessed. In addition, both frameworks are accessible and relevant as they have been tested and validated internationally, with various information sources available for their use.

The second objective was geared to understand how these outcomes were measured. The review aimed to list tools of assessment matched to outcomes and to contribute to the understanding of the outcome. The assessment tools of the included studies have been charted (both qualitative and quantitative) and shown to be heterogeneous for similar outcomes targeted. A widespread measurement tool was the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which measures the orientation to time, place, registration of three words, language, and constructive visual capacity. Video recording and analysis (in various forms) showed to be a standard method for qualitative studies.

The third objective was to gain an overview of interventions applied to address the respective outcomes. Regarding the interventions used, DMT was most frequently used (11 out of 25 studies). Its holistic approach is mirrored in measuring outcomes frequently in more than two domains of the body. However, not all DMT studies chose to measure various domains. There are further dance interventions such as Latin ballroom dancing (DANZÓN), Preventing Loss of Independence via Exercise (PLIÉ), therapeutic circle dancing and dancing that address a wide range of the DOF domains and ICF components. Some of these explicitly include or draw on DMT, while others draw on other disciplines for a therapeutic approach to dancing. The main difference in interventions seems to be whether they include psychological aspects (emotional, social, cultural, integration) or focus on the body’s physical and cognitive domains. However, the reader should keep in mind that the outcomes measured in the studies do not necessarily encompass all the domains reached via the intervention, as a particular domain may not be the target of the research question. Tab. 5.7 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] matches the types of interventions used with outcomes measured, helps identify patterns and gives an informed overview of existing interventions.

The wide range of outcomes measured reflects the various approaches towards people living with dementia and to dementia as a diagnosis. For example, some focus on the micro-body functions (memory), others focus on the daily experience (getting dressed), and others zoom out further to the social, contextual realities (care services). These are not mutually exclusive but often combined. Rather than merely listing the outcomes, this scoping review has synthesized these with the help of two frameworks, with the hope of encouraging consistency and common language for future research. The ICF framework proves helpful to capture these various perspectives that often reflect different disciplinary approaches. The DOF provides a valuable overview of the various domains of self that can be considered.

4.2 Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Only one person (CC) did the study selection, data charting, and synthesis of results. To reduce the likelihood of mistakes, the author has set up data charting methods that require double/triple checking to reduce possible mistakes and include always going back to the original text. The second author (SK) was referred to if there were uncertainties. Additionally, a strengthened emphasis has been placed on transparency so that the decisions and selections are traceable. These various stages of selecting the results, data charting, individual critical appraisal and synthesis is included as attachment.

The last search conducted April 2021 is a limitation as it does not include most recent results. However, the value of synthesizing results to the two frameworks remains relevant. The authors are not aware of more recent studies assessing outcomes of DMT/dance interventions with participants with dementia. This has not been systematically verified.

A further limitation is that this review only includes studies written in English. Furthermore, the quality of some studies is low as critical appraisal was not part of the selection criteria but rather done as a reference once the studies were selected. This is the case, because the research question does not aim to gain insight into evidence but of included outcomes, which is why we did not restrict the selection in terms of study design or quality. The critical appraisal for mixed-methods studies, was done separately assessing quantitative and qualitative aspects, thereby not assessing whether the mixed methods have been adequately combined. This could have been alleviated by using a mixed method assessment tool such as the Mixed Methods Appraisal tool (MMAT) [85]. While this also includes explanations, the first author evaluated the tools developed by the JBI as more elaborate and comprehensive, which is the reason for assessing mixed methods studies twice, because there is no checklist for this study type by the JBI.

Another aspect that the reader should keep in mind is that research ethics is not addressed in this review. However, it is an essential component of doing research well, and Coaten [20] as well as Lyons [78] elaborate this aspect comprehensively. The implementation process of interventions in various settings was not addressed as it was not part of the research question. Nevertheless, the author would like to highlight for the reader that this is another important aspect also for the realization of an intervention.

4.3 Conclusions

This scoping review has provided two accessible and relevant frameworks that provide an overview of what health and well-being effects DMT/dance interventions can have for older adults with dementia. The frameworks presented here include the wide range of outcomes from memory to mobility to engagement to socializing to the overall quality of life. The authors suggest that these frameworks serve as an orientation rather than a checklist for research, policy, and practice.

This scoping review extends existing systematic reviews on the topic with studies published after 2018 to April 2021. Furthermore, it has contributed to the existing literature by giving a combined overview of DMT and dance interventions for older adults with dementia. This combination aimed to improve constructively the inconsistency of how interventions are conceived. The review process showed that the outcomes expected cannot reliably be linked to the name of the intervention. Therefore, the detailed description of the intervention is essential (e.g., to facilitate replicability).

This review agrees with past reviews [35], [36], [39], [40] that the quality of research remains low, although the recent RCT by Ho et al. [38] strengthens this base considerably. The base suggests that due to its embodied, non-verbal approach, the therapeutic use of dance is an auspicious way of engaging and activating resources for participants, as well as alleviating symptoms. As such, DMT and dance interventions are a promising form of non-pharmacological treatment, as they address clinical, behavioral as well as well-being outcomes.

Ongoing research around embodied selfhood, embodied cognition, neuroplasticity, and body memory provide an interesting insight into why this may be so. The two frameworks may serve as a starting point for further research that studies the process behind the health and well-being effects of DMT/dance interventions for older adults with dementia. As the ICF is seen as separate from etiology, it provides space to engage sincerely with different approaches such as embodied intelligibility, despite the ICD describing dementia as a cerebral dysfunction; in addition, providing an inter-disciplinary language as a common ground for future interdisciplinary research. This review excluded studies with participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), however, this could be another valuable avenue of further research to start earlier in the progression of the symptoms. For improved research quality, the author hopes that the criteria of the JBI critical appraisal serve as a reference point of how quality can be assessed. Furthermore, the list of methodological tools can provide a starting point for more consistent ways of gathering data.

As suggested by Levac et al. [86] a further stage of this scoping review could be to test the usefulness of these frameworks with relevant stakeholders. In line with a person-centered care approach, both frameworks offered here are accessible for formulating goals ‘bottom-up’ [87] together with the person with dementia and their caretakers/family members. This form of research enables persons with dementia to contribute outcomes that are a priority for them. In addition, the matching of the outcomes to the ICF and the DOF could be reviewed by other practitioners and researchers for consensus. If they prove useful to stakeholders, the frameworks presented in this study can provide a reliable overview of the various domains that can be addressed through the work of practitioners and help locate their approach and way of working. In a clinical setting, the ICF can serve as a common language for interdisciplinary communication, to frame respective outcomes. The DOF can be used for clinical assessment and planning; the Movement Assessment and Reporting App (MARA) is based on the DOF and offers innovative ways to evaluate and document therapeutic process. Alternatively, there are various established assessment sheets that provide a way to operationalize the framework.

Much like dance, the two frameworks combined (shown in Figure 2 [Fig. 2]) are a multi-modal creation that provides various perspectives across space, time, and form. Spatially, one can investigate the body functions level, explicitly targeting memory or zoom further out to daily life practices such as communication. In addition, the environmental factors provide a view of the care situation and society more broadly. Furthermore, the domains from the Dunphy Outcomes Framework (DOF) are a reminder of the various forms of self: physical, cultural, emotional, cognitive, social, and the integration.

Figure 2: Combined view of ICF, DOF and Kitwood’s main psychological needs flower

The specific and the holistic both play an essential role in supporting informed person-centered care, across time. There is no doubt that the symptoms of dementia are a source of great suffering to persons affected and their caretakers. However, due to its multi-modality, this perspective, nurtured by Kitwood’s primary psychological needs [88] of love, attachment, inclusion, occupation, identity, and comfort offers creative space to work across disciplines continuously. Following the aim to alleviate suffering, while striving towards a life that is characterized not just by survival, but by belonging, being loved and celebrated.

5 Supplementary material

Refer to Attachment 1 [Att. 1] for the following supplements:

5.1 Reasoning where study inclusion unclear

5.2 Critical appraisal notes

5.3 Outcomes matched to ICF sub-category

5.4 Data charting of individual sources of evidence

5.5 Results of critical appraisal (summarized in table via study design)

5.6 Method and time of measurement matched to frameworks

5.7 Interventions matched to outcomes and frameworks

Notes

Author contribution

The first author (CC) wrote the initial draft, charted the individual data, and synthesized the outcomes. The second author (SK) provided independent view when there were uncertainties regarding study inclusion and data charting. Both authors contributed to manuscript production and revision of the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Research Institute for Creative Arts Therapies (RIArT) at Alanus University for Arts and Social Sciences in Alfter/Bonn, Germany, for financing the formatting of the initial M.A. thesis into an article. We would also like to thank the SRH librarian Armin Vetter for revising the search strategy.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: WHO; 1993.[2] Tible OP, Riese F, Savaskan E, von Gunten A. Best practice in the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2017 Aug;10(8):297-309. DOI: 10.1177/1756285617712979

[3] Bennett CG, Fox H, McLain M, Medina-Pacheco C. Impacts of dance on agitation and anxiety among persons living with dementia: An integrative review. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(1):181-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.07.016

[4] Stoppe G. Demenz. 2nd ed. Munich: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag; 2007.

[5] Douglas S, James I, Ballard C. Non-pharmacological interventions in dementia. Advances in psychiatric treatment. 2004;10(3):171-7. DOI: 10.1192/apt.10.3.171

[6] Zucchella C, Sinforiani E, Tamburin S, Federico A, Mantovani E, Bernini S, Casale R, Bartolo M. The Multidisciplinary Approach to Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia. A Narrative Review of Non-Pharmacological Treatment. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1058. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01058

[7] Corbett A, Burns A, Ballard C. Don't use antipsychotics routinely to treat agitation and aggression in people with dementia. BMJ. 2014 Nov;349:g6420. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.g6420

[8] Creese B, Da Silva MV, Johar I, Ballard C. The modern role of antipsychotics for the treatment of agitation and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018 Jun;18(6):461-7. DOI: 10.1080/14737175.2018.1476140

[9] Douglas IJ, Smeeth L. Exposure to antipsychotics and risk of stroke: self controlled case series study. BMJ. 2008 Aug;337:a1227. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.a1227

[10] Heser K, Luck T, Röhr S, Wiese B, Kaduszkiewicz H, Oey A, Bickel H, Mösch E, Weyerer S, Werle J, Brettschneider C, König HH, Fuchs A, Pentzek M, van den Bussche H, Scherer M, Maier W, Riedel-Heller SG, Wagner M; (shared last authorship) for the AgeCoDe & AgeQualiDe study groups. Potentially inappropriate medication: Association between the use of antidepressant drugs and the subsequent risk for dementia. J Affect Disord. 2018 Jan;226:28-35. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.016

[11] Hwang PW, Braun KL. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions to Improve Older Adults' Health: A Systematic Literature Review. Altern Ther Health Med. 2015 Sep-Oct;21(5):64-70.

[12] Gallagher S. How the body shapes the mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. DOI: 10.1093/0199271941.001.0001

[13] Shapiro L. Embodied cognition. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 2019. DOI: 10.4324/9781315180380

[14] Teixeira-Machado L, Arida RM, de Jesus Mari J. Dance for neuroplasticity: A descriptive systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019 Jan;96:232-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.010

[15] Kontos P, Grigorovich A. Dancing with dementia: Citizenship, embodiment and everyday life in the context of long-term care. In: Katz S, editor. Ageing in everyday life: Materialities and embodiments. Bristol: Bristol University Press; 2018. p. 163-80. (Ageing in a global context). DOI: 10.46692/9781447335924.012

[16] Kontos P, Grigorovich A. Integrating Citizenship, Embodiment, and Relationality: Towards a Reconceptualization of Dance and Dementia in Long-Term Care. J Law Med Ethics. 2018 Sep;46(3):717-23. DOI: 10.1177/1073110518804233

[17] Baer U, Schott-Lange G. Das Herz wird nicht dement. Rat für Pflegende und Angehörige. Weinheim: Beltz; 2017.

[18] Fuchs T. Leiblichkeit und personale Identität in der Demenz. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie. 2018;66(1):48-61. DOI: 10.1515/dzph-2018-0005

[19] Koch SC. Das Leibgedächtnis bleibt bei Demenz erhalten. Psychotherapie im Alter. 2021;16(1):35-48.

[20] Coaten RB. Building bridges of understanding: The use of embodied practices with older people with dementia and their care staff as mediated by dance movement psychotherapy [dissertation]. London: University of Roehampton; 2009.

[21] Berger M. Bodily Experience and Expression of Emotion. American Journal of Dance Therapy. 1972.

[22] Coaten R, Newman-Bluestein D. Embodiment and dementia--dance movement psychotherapists respond. Dementia (London). 2013 Nov;12(6):677-81. DOI: 10.1177/1471301213507033

[23] Dosamantes-Beaudry I. The arts in contemporary healing. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2003.

[24] Gallese V. The roots of empathy: the shared manifold hypothesis and the neural basis of intersubjectivity. Psychopathology. 2003;36(4):171-80. DOI: 10.1159/000072786

[25] Chang M, Newman-Bluestein D. Creative Approaches to Enhancing Relationships with People with Dementia. In: Lesley University Community of Scholars Day; 2018 Mar 28; Cambridge. 11.

[26] Kitwood T. The experience of dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 1997;1(1):13-22. DOI: 10.1080/13607869757344

[27] Eberhard M. Tanztherapie: Indikationsstellung, Wirkfaktoren, Ziele. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland, editor. Kreativtherapien: Wissenschaftliche Akzente und Tendenzen. Pulheim: Rhein-Eifel-Mosel Verlag; 2003. p. 110-31.

[28] Koch SC, Eberhard-Kaechele M. Wirkfaktoren der Tanz- und Bewegungstherapie. Replik auf Tschacher, Munt und Storch. körper-tanz-bewegung. 2014;2(4):150-9. DOI: 10.2378/ktb2014.art24d

[29] Willke E. Tanztherapie. Theoretische Kontexte und Grundlagen der Intervention. Bern: Hans Huber; 2010.

[30] Scarth S. What is Dance Movement Therapy (DMT)? EADMT: 2021. Available from: https://eadmt.com/what-is-dance-movement-therapy-dmt

[31] Lapum JL, Bar RJ. Dance for Individuals With Dementia. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016 Mar;54(3):31-4. DOI: 10.3928/02793695-20160219-05

[32] Baker FA, Lee YC, Sousa TV, Stretton-Smith PA, Tamplin J, Sveinsdottir V, Geretsegger M, Wake JD, Assmus J, Gold C. Clinical effectiveness of music interventions for dementia and depression in elderly care (MIDDEL): Australian cohort of an international pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022 Mar;3(3):e153-e165. DOI: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00027-7

[33] Odell-Miller H, Blauth L, Bloska J, Bukowska AA, Clark IN, Crabtree S, Engen RB, Knardal S, Kvamme TK, McMahon K, Petrowitz C, Smrokowska-Reichmann A, Stensæth K, Tamplin J, Wosch T, Wollersberger N, Baker FA. The HOMESIDE Music Intervention: A Training Protocol for Family Carers of People Living with Dementia. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2022 Dec;12(12):1812-32. DOI: 10.3390/ejihpe12120127

[34] de Witte M, Orkibi H, Zarate R, Karkou V, Sajnani N, Malhotra B, Ho RTH, Kaimal G, Baker FA, Koch SC. From Therapeutic Factors to Mechanisms of Change in the Creative Arts Therapies: A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:678397. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397

[35] Mabire JB, Aquino JP, Charras K. Dance interventions for people with dementia: systematic review and practice recommendations. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019 Jul;31(7):977-87. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610218001552

[36] Karkou V, Meekums B. Dance movement therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2(2):CD011022. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011022.pub2

[37] Karkou V, Aithal S, Richards M, Hiley E, Meekums B. Dance movement therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Aug;8(8):CD011022. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011022.pub3

[38] Ho RTH, Fong TCT, Chan WC, Kwan JSK, Chiu PKC, Yau JCY, Lam LCW. Psychophysiological Effects of Dance Movement Therapy and Physical Exercise on Older Adults With Mild Dementia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 Feb 14;75(3):560-70. DOI: 10.1093/geronb/gby145

[39] Lyons S, Karkou V, Roe B, Meekums B, Richards M. What research evidence is there that dance movement therapy improves the health and wellbeing of older adults with dementia? A systematic review and descriptive narrative summary. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2018;60:32-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2018.03.006

[40] Jiménez J, Bräuninger I, Meekums B. Dance movement therapy with older people with a psychiatric condition: A systematic review. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2019;63:118-27. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2018.11.008

[41] Dunphy K, Lebre P, Mullane S. Outcomes Framework for Dance Movement Therapy. V. 81. 2020. Available from: https://www.makingdancematter.com.au/about/outcomes-framework/

[42] Meyer C, O'Keefe F. Non-pharmacological interventions for people with dementia: A review of reviews. Dementia (London). 2020 Aug;19(6):1927-54. DOI: 10.1177/1471301218813234

[43] Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018 Nov;18(1):143. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

[44] Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct;169(7):467-73. DOI: 10.7326/M18-0850

[45] Chita DS, Docu A, Stuparu AS, Docu AF, Stroe AZ. Dance movement therapy influence the quality of life and has behavioral improvements in dementia patients. Ovidius University Annals, Physical Education and Sport/Science, Movement and Health. 2020;20(2):91-6.

[46] Arakawa-Davies K. Dance/movement therapy and reminiscence: a new approach to senile dementia in Japan. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 1997;24(3):291-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0197-4556(97)00031-2

[47] Hill H. An attempt to describe and understand moments of experiential meaning within the dance therapy process for a patient with dementia [Master thesis]. Bundoora: La Trobe University; 1995.

[48] Wilkinson N, Srikumar S, Shaw K, Orrell M. Drama and movement therapy in dementia: A pilot study. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 1998;25(3):195-201. DOI: 10.1016/S0197-4556(97)00102-0

[49] Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179-87. DOI: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

[50] Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. DOI: 10.46658/JBIRM-17-03

[51] Duignan D, Hedley L, Milverton R. Exploring dance as a therapy for symptoms and social interaction in a dementia care unit. Nurs Times. 2009 Aug 4-17;105(30):19-22.

[52] World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2001.

[53] McDougall J, Wright V, Rosenbaum P. The ICF model of functioning and disability: incorporating quality of life and human development. Dev Neurorehabil. 2010;13(3):204-11. DOI: 10.3109/17518421003620525

[54] Hanna JL. The power of dance: health and healing. J Altern Complement Med. 1995;1(4):323-31. DOI: 10.1089/acm.1995.1.323

[55] Thyrian JR, Kracht F, Nikelski A, Boekholt M, Schumacher-Schönert F, Rädke A, Michalowsky B, Vollmar HC, Hoffmann W, Rodriguez FS, Kreisel SH. The situation of elderly with cognitive impairment living at home during lockdown in the Corona-pandemic in Germany. BMC Geriatr. 2020 Dec;20(1):540. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-020-01957-2

[56] Schoenenberger-Howie S, Dunphy KF, Lebre P, Schnettger C, Hillecke T, Koch SC. The Movement Assessment and Reporting App (MARA) for Music Therapy. GMS J Art Ther. 2022;4:Doc03.

[57] Lebre P, Dunphy K, Juma S. Exploring use of the Outcomes Framework for Dance Movement Therapy to establish a group profile and objectives for psychomotor therapy interventions. Body Mov Dance Psychother. 2020;15(4):251-66. DOI: 10.1080/17432979.2020.1806926

[58] Takahashi H, Matsushima K, Kato T. The effectiveness of dance/movement therapy interventions for autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Am J Dance Ther. 2019;41(1):55-74. DOI: 10.1007/s10465-019-09296-5

[59] Dunphy K, Lebre P, Dumaresq E, Schoenenberger-Howie SA, Geipel J, Koch SC. Reliability and short version of the Dunphy Outcomes Framework (DOF): Integrating the art and science of dance movement therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2023;85:102063. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2023.102063

[60] Barnes AJ. Creating Connection through Dance/Movement Therapy among Older Adults with Dementia: Development of a Method [Master thesis]. Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 2020:305.

[61] Berg B. Dance/Movement Therapy and the Quality of Life for Individuals with Late Stage Dementia: A Clinical Method [Master thesis]. Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 2020:334.

[62] Coaten R, Heeley T, Spitzer N. Dancemind's' moving memories' evaluation and analysis; a UK based dance and health project for people living with dementia and their care-staff. UNESCO observatory multi-disciplinary journal in the arts. 2013;3(3):1-17.

[63] Guzmán-García A, Mukaetova-Ladinska E, James I. Introducing a Latin ballroom dance class to people with dementia living in care homes, benefits and concerns: a pilot study. Dementia (London). 2013 Sep;12(5):523-35. DOI: 10.1177/1471301211429753

[64] Kowarzik U. Opening doors: Dance movement therapy with people with dementia. In: Payne H, editor. Dance movement therapy: Theory, research and practice. London: Routledge; 2006. p. 17-30.

[65] Nyström K, Lauritzen SO. Expressive bodies: demented persons' communication in a dance therapy context. Health (London). 2005 Jul;9(3):297-317. DOI: 10.1177/1363459305052902

[66] Smith N, Waller D, Colvin A, Hayes J, Naylor M. Dance and Dementia Project: findings from the pilot study. Brighton: University of Brighton; 2012.

[67] Wang H. The Effectiveness of Dance Movement Therapy with Elderly Women Who Have Dementia [Master thesis]. Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 2019:230.

[68] Wu E, Barnes DE, Ackerman SL, Lee J, Chesney M, Mehling WE. Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ): qualitative analysis of a clinical trial in older adults with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(4):353-62. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2014.935290

[69] Barnes DE, Mehling W, Wu E, Beristianos M, Yaffe K, Skultety K, Chesney MA. Preventing loss of independence through exercise (PLIÉ): a pilot clinical trial in older adults with dementia. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0113367. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113367

[70] Dayanim S. The acute effects of a specialized movement program on the verbal abilities of patients with late-stage dementia. Alzheimer's care today. 2009;10(2):93-8.

[71] Guzmán A, Freeston M, Rochester L, Hughes JC, James IA. Psychomotor Dance Therapy Intervention (DANCIN) for people with dementia in care homes: a multiple-baseline single-case study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016 Oct;28(10):1695-715. DOI: 10.1017/S104161021600051X

[72] Hameed S, Shah JM, Ting S, Gabriel C, Tay SY, Chotphoksap U, Liong A. Improving the Quality of Life in Persons with Dementia through a Pilot Study of a Creative Dance Movement Programme in an Asian Setting. Int J Neurorehabil. 2018;5(6):1000334. DOI: 10.4172/2376-0281.1000334

[73] Hokkanen L, Rantala L, Remes AM, Härkönen B, Viramo P, Winblad I. Dance/Movement Therapeutic methods in management of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Apr;51(4):576-7. DOI: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51175.x