[Führungsverhalten leitender Hebammen und Organisationales Commitment – eine quantitative Befragung im Krankenhaus tätiger Hebammen in Deutschland]

Irina Blissenbach 1Michael Schuler 2

Nicola H. Bauer 3

1 Linden, Germany

2 University of Applied Sciences – Hochschule für Gesundheit Bochum, Germany

3 University of Cologne, Germany

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Der Hebammenmangel in Krankenhäusern in Deutschland unterstreicht die Relevanz, die Verbundenheit von Hebammen zum Krankenhaus zu fördern (Organisationales Commitment, OC). Die Transformationale Führung (TF) – ein vorbildhafter, inspirierender, intellektuell herausfordernder, wertschätzender Führungsstil – korreliert positiv mit OC. Führung bei Hebammen in Deutschland ist nicht erforscht.

Ziel: Ziel ist die Darstellung des Führungsverhaltens leitender Hebammen aus Sicht klinisch tätiger Hebammen und Überprüfung eines multivariaten Zusammenhangs zwischen TF und OC.

Methodik: Klinisch tätige Hebammen (N=111) wurden online mit dem „Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire“ und „Organisational Commitment Questionnaire“ befragt (November–Dezember 2020). Die Analyse erfolgte deskriptiv, mit Pearson-Korrelation und multipler linearer Regression.

Ergebnisse: TF der leitenden Hebammen wird selten bis manchmal von den Befragten wahrgenommen (1,77≤M≤2,12; Skala: 0 bis 4). Das OC ist im Durchschnitt M=1,69 (Skala: 0 bis 4). Ein signifikanter Zusammenhang zwischen TF und OC zeigt sich nur in der bivariaten Analyse (r=0,34).

Schlussfolgerung: Forschungsbedarf besteht mit einer größeren, repräsentativeren Stichprobe und zur Arbeitssituation leitender Hebammen. TF der Leitungen und das OC der Hebammen sind niedrig. Dies zeigt Handlungsbedarf. Bedeutsam für OC zeigen sich in der multivariaten Analyse das Engagement der Krankenhausleitung, die Reduktion arbeitsbezogenen Stresses und die Verbesserung der Teamatmosphäre.

Schlüsselwörter

Führung, Leitung, klinische Hebammenarbeit, transformationale Führung, Organisationales Commitment

Background

Problem 1: Lack of data on leadership in the context of midwifery in Germany

Leadership is a relevant factor influencing work satisfaction, employee health, organisational commitment (see below for a definition), the intention to leave midwifery and the quality of healthcare [21], [23], [38], [43], [47]. Yet, so far, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies on leadership behaviour in the context of the midwifery in Germany.

Leadership in the German healthcare system

In 1996, as the first German federal state to do so, Berlin issued a further education regulation for the ‘training of nurses in management functions’ [1]. Since the first quality assurance guideline for premature and full-term infants (QFR-RL) was published in 2006, it has been compulsory for midwife managers in perinatal centres across Germany to complete ‘leadership’ training [20]. In 2007, for the first time, the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) published a document on the subject of ‘leadership’. The document was entitled ‘Curriculum for medical leadership’ for the training and continuing professional development of physicians in managerial positions [11].

It is not known exactly how many midwife managers there are in Germany. The terms senior midwife, midwife manager, management and manager are used interchangeably in this article. They refer to a midwife working in a hospital in a management position, not as a deputy, who has a team of midwives and sometimes other qualified staff reporting directly to her/him.

Transformational leadership

Transformational leadership (TL) is characterised by the exemplary behaviour of the manager, who communicates a vision for the future, intellectually challenges those they are managing and also shows their appreciation for their employees and treats them as individuals [49]. Midwifery researchers propose TL for the midwifery field, arguing that there are overlaps between this type of leadership behaviour and women-centred midwifery care [9], [12]. Transformational leadership comprises the following five dimensions of leadership behaviour:

- ldealised Influence behaviour (IIb): The manager behaves in an exemplary manner from an ethical and moral perspective and conveys high standards [6], [35].

- ldealised Influence attributed (IIa): Employees see the manager as an outstanding person/a role model (charisma), admire and trust them [6], [49].

- lnspirational Motivation (IM): IM describes how the manager involves their staff in developing an attractive vision for the future. They express optimism that collective goals will be achieved, convey enthusiasm and demonstrate the purpose of the work [6], [49].

- lntellectual Stimulation (IS): Employees are motivated to seek creative solutions and to question existing assumptions. They are intellectually challenged by the manager and encouraged to contribute their own ideas [6], [49].

- lndividual Consideration (IC): The manager knows the preferences and needs of those they are managing and functions as a coach and mentor. The manager asks questions, listens, supports and treats each member of the team as an individual [6], [49].

Transformational leadership is part of the ‘Full Range of Leadership Model’ developed by Bass and Avolio [6], which also encompasses ‘transactional’ and ‘passive’ leadership. Transactional leadership comprises the dimensions ‘Management by Exception active’ (MbEa) and ‘Contingent Reward’ (CR) and describes a leadership style which rewards performance and actively works to counter mistakes [49]. The passive leadership style comprises the dimensions ‘Management by Exception passive’ (MbEp) and ‘Laissez-faire’ (LF) and is about avoiding active leadership [49]. According to the aforementioned model, a successful manager demonstrates a high degree of TL, a moderate degree of transactional leadership behaviour and little to no passive leadership behaviour [6].

Four studies were found which examined transformational, transactional and passive leadership in the context of nursing and medical work in hospitals in Germany [25], [28], [42], [48]. Compared with a cross-sectoral sample (N=1,267) in Germany [39], the values for transformational leadership dimensions in the studies from the care sector are high. Only the high value of LF in the study by Schmidt-Huber stands out negatively [42].

Problem 2: Midwife shortage

Leadership should also be examined against the backdrop of a shortage of midwives in hospitals in Germany, as leadership is found to be associated with organisational commitment (OC) [10].

Organisational commitment

Employees with a high OC identify with their organisation and its values and want to remain part of the company for which they are working [46]. They are prepared to invest labour and energy to contribute to the organisation’s success [34]. Organisational commitment is negatively correlated (r=0.46) with the intention to resign [30].

Shortage of midwives in German hospitals

Hospitals in Germany are facing a midwife shortage [2], [36]. In order to meet the demand for midwives as set out in the guideline ‘Recommendations on the Structural Prerequisites for Perinatal Care in Germany’, the federal state of Hesse, for example, would need 22% more midwives in hospitals by 2030 [8]. Moreover, in a study conducted in North Rhine-Westphalia, 60% of midwives working in hospitals reported having entertained the idea of giving up their jobs in the last six months [36]. In one survey, the reason midwives most frequently gave for contemplating reducing their hours in the hospital or giving up their work there entirely was ‘overly high workload’ [2]. There is evidence that the midwife shortage in hospitals has an impact on the workload of midwives and thus on their health and well-being [44]. A total of 45% of midwives working in hospitals in North Rhine-Westphalia report that they rarely manage to take the mandatory break during their shift [2]. In another study, 29.6% of midwives working in hospitals describe their health as ‘not so good’ or ‘bad’. This is significantly more often the case for midwives working in hospitals [36].

Transformational leadership and organisational commitment

Felfe [17] attaches great importance to managers when it comes to strengthening OC. According to Bass and Riggio [6], every dimension of TL helps facilitate OC. International studies from the care sector show a positive correlation between TL and employees’ OC [4], [10].

Aims

Transformational leadership may be suitable for the field of midwifery and may also have a positive impact on midwives’ OC. In light of the midwife shortage in hospitals, the latter is particularly relevant.

Bearing this in mind, the present study investigates the following:

- The extent to which senior midwives in Germany demonstrate leadership behaviour in accordance with the Full Range of Leadership Model in the view of midwives who (formerly) worked in hospitals

- Whether there is a correlation between TL and OC if social and organisational working conditions are controlled

Method

Design

This is a cross-sectional study conducted as part of a Master’s thesis.

Inclusion criteria

Participants must be midwives who, in the last five years, worked in Germany under a midwife as their line manager for at least six months. Midwives working for a hospital on a freelance basis could also participate, as could midwives who were taking a break from their hospital work at the time or had left their jobs entirely.

Data collection

In order to raise awareness of the survey, we made a video. This was shared via social media, including a Facebook group with 5,575 midwife members, the alumni mailing list for the University of Applied Sciences in Bochum and the website of the German Society of Midwifery Science. We also wrote to all federal state branches of the German Midwifery Association asking them to distribute the survey to their members. Eight branches (BB, BE, BW, BY, HB, HH, NRW, TH) and the Bochum regional group responded to the request. The recruitment of the study participants took place from 16 November 2020 and the survey could be accessed via the SosciSurvey portal [26] from 23 November 2020 to 14 November 2020. No material incentives were offered.

Sample size

G*Power was used to calculate a priori that a minimum sample size of 150 is required to be able to yield statistically significant findings for effects of r≥0.260 in bivariate correlation analyses (alpha level: 0.05; beta level: 0.10) [15].

Survey instrument

The online questionnaire takes approximately 30 minutes to complete. The survey includes two validated survey instruments, individual items from questionnaires developed by other researchers and exploratory questions.

To collect information on leadership behaviour, we used the ‘Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire 5x short’ (MLQ) in the German translation by Rowold [39]. Based on 36 statements on a specific type of leadership behaviour, participants rate the extent to which they perceive this behaviour in their manager on a five-point rating scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (frequently, if not always). Four items each form the basis for a subscale, which illustrates one of the nine dimensions of leadership behaviour according to the Full Range of Leadership Model [39]. Subscales are treated as interval scaled. The MLQ also includes items to determine success factors of leadership, of which the perceived effectiveness of the manager (EF) and satisfaction with the manager (SAT) are analysed.

Information on OC was collected using the ‘Organisational Commitment Questionnaire’ by Porter and Smith in the German translation by Maier and Woschée [31]. This provided a unidimensional measurement of OC and, in line with Meyer et al. [32], covers affective commitment, in particular. We also added to the nine items in the short version of the questionnaire a negatively formulated item from the long version. On a five-point scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), respondents rate their commitment to the hospital in which they work or have worked.

Besides basic data about the participants and data on their place of work and managers, questions were also asked about organisational and social working conditions:

- Hospital management’s support for this area of work (based on [44])

- Work-related stress: Single items from the categories stress, demands and worries from the Perceived Stress Questionnaire which respondents were required to answer concerning the workplace [19]

- Team atmosphere (formulated by the authors)

A pretest of the questionnaire was conducted with two midwives with and two without a university degree. Subsequently, individual items were reformulated and a free text field added at the end.

Data analysis

A total of N=159 midwives took part in the survey but only N=111 cases could be analysed. In 35 cases, the questionnaire was abandoned in the first third, in one case there was technical problem and for the remaining 11 cases it was decided on an individual basis that they should be excluded due to the very large number of missing values in the areas of leadership behaviour and OC.

To conduct the data analysis SPSS 25 and Jamovi 1.6.15 [45] were used. An alpha level of 5% is applied for all significance tests.

Research objective 1: To answer the first question, the distribution of the data was analysed using location and dispersion parameters as well as graphically using bar charts and Whisker boxplot diagrams. In particular, the mean values of the subscales were calculated.

Research objective 2: To achieve the second research objective, we first conducted Pearson correlation tests followed by multiple linear regression analyses. The regression analysis was hierarchical with ‘blockwise’ entry. It was tested for absence of multicollinearity, linearity of the correlations, normal distribution of the residues and homoscedasticity. Because the individual dimensions of the TL were highly correlated with one another (0.472≤r≤0.840), it was not possible to include them in the model at the same time due to multicollinearity. An averaged subscale ‘transformational leadership’ was therefore created and included. This was also done with the items collecting information about work-related stress. Further, the variables ‘hospital management’s support’ and ‘team atmosphere’ were added to the model as predictors. The inclusion of other variables such as ‘satisfaction with pay’ did not result in a significant improvement of R2, but did result in an increase in multicollinearity. When the variable ‘team atmosphere’ was included, the model was thus considered ‘saturated’. No control variables such as age or educational status were included as these would have considerably reduced the number of cases for analysis due to missing values. Moreover, no bivariate correlations were found between these variables and OC.

Explorative analysis: In addition to this, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the assessment of senior midwives with and without leadership training.

Data protection and ethical considerations

Data collection was anonymous and the principle of data economy was observed [14]. In order to preserve anonymity, among other things, no information on the hospital birth rate or organisational form was collected (freelance, employment or fee-based). The legal data protection regulations of the German Data Protection Act, the Data Protection Act of the Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) were adhered to. The data will be securely stored for a period of ten years, only accessible to members of the project team.

The research project was reviewed by the Ethics Commission of the University of Applied Sciences Bochum and the implementation of the study was approved by an ethics vote on 15 November 2020.

Results

First, the characteristics of the sample and the perceived leadership behaviour of the managers being assessed are described. The findings regarding the correlation between TL and OC are then presented, followed by the findings of the explorative analysis.

Characteristics of the respondents

The respondents were, on average, 34.7 years of age (SD=9.97; Md=31.50, Missing=3).

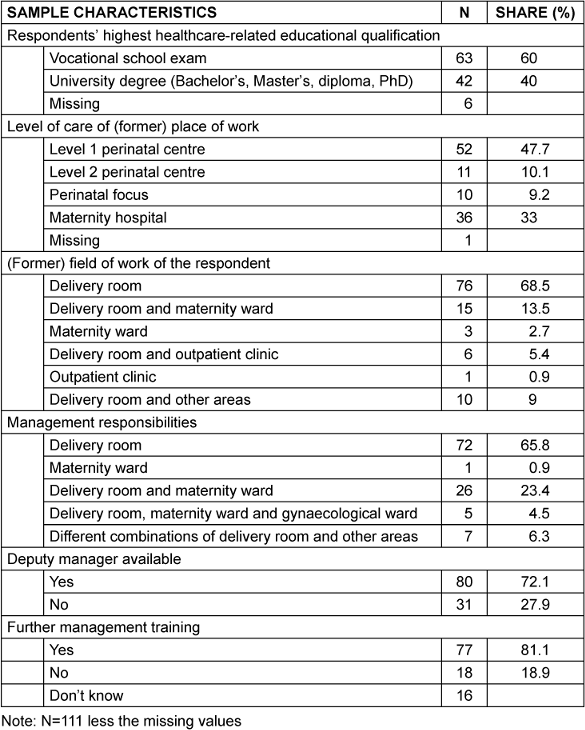

At the time of the survey, 80.2% (n=89) of the participants were working as midwives in a hospital (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]). The reasons respondents gave for having left clinical midwifery included working conditions (n=14), quality of healthcare (n=10) and pay (n=9; multiple responses possible).

Table 1: Characteristics of the respondents, the respondents’ work and the managers being assessed

Characteristics of the respondents’ managers

Respondents rated the hospital management’s support for the area of work on average at 1.50 (SD=1.19) which corresponds to barely (supportive) to moderately (supportive). Only 22.0% of the midwives surveyed found that the hospital management was quite (n=17) or extremely (n=7) supportive of their area of work (N=109; missing=2) (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]).

Leadership behaviour according to the Full Range of Leadership Model

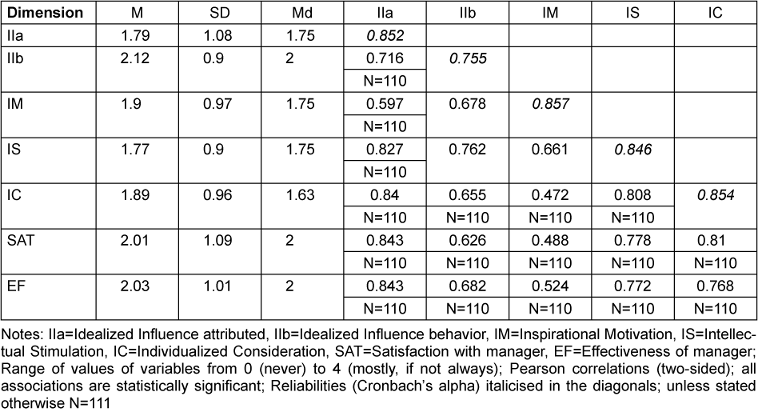

Four of the five dimensions of TL received average values of less than two (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]). Only the IIb dimension was observed slightly more than ‘sometimes’ (2) by those being managed. The respondents perceived the IS dimension in their managers least of all (M=1.77; SD=0.90).

Table 2: Average values, standard deviations, intercorrelations and Cronbach’s alpha of the dimensions of transformational leadership and outcomes ‘satisfaction with manager’ (SAT) and ‘perceived effectiveness of management’ (EF)

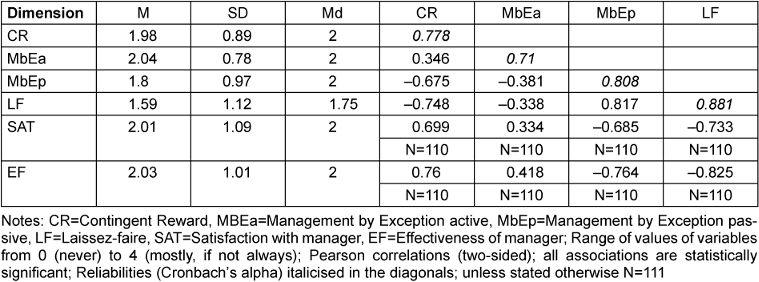

Apart from the dimension MbEa (M=2.04), the transactional and passive leadership dimensions were observed among managers between ‘rarely’ and ‘sometimes’ (see Table 3 [Tab. 3]).

Table 3: Average values, intercorrelations and Cronbach’s alpha of the dimensions of transactional leadership and passive leadership and the outcomes ‘satisfaction with manager’ (SAT) and ‘perceived effectiveness of the manager’ (EF)

Transformational leadership and organisational commitment

On average, the OC in the sample stands at M=1.69 (SD=0.81; Md=1.60; N=111, scale from 0 ‘I strongly disagree with this statement’ to 4 ‘I strongly agree with this statement’).

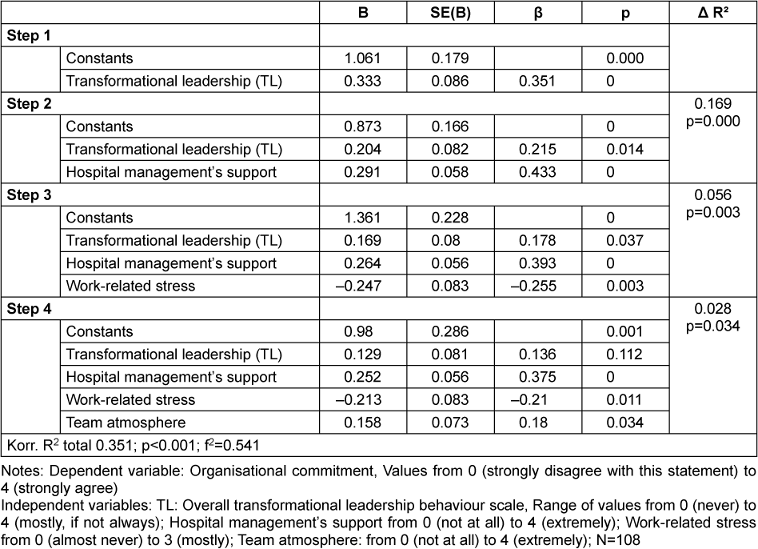

Bivariate analyses show medium to high correlations of the variable TL (r=0.343; p=0.000), hospital management’s support for the area of work (r=0.500; p=0,000), work-related stress (r=–0.347; p=0.000) and team atmosphere (r=0.342; p=0.000) with the independent variable OC. In the multivariate analysis, the variables listed explain 35.1% of the variance of OC (corr. R2=0.351; F(4; 104)=15.613; p<0.001; N=109). The goodness of fit of the model is high at f2=0.541 ([27], p. 576). When the variable team atmosphere is included, the TL is no longer a significant predictor (see Table 4 [Tab. 4]). The largest improvement of the OC can be expected with an increase in the hospital management’s support. If this is increased by one unit step, an improvement in the OC of 0.252 can be expected (on a scale from 0 to 4). Other significant factors are perceived work-related stress (B=–0.213; SE(B)=0.083; p=0.011; 95%KI for B [–0.377; –0.049]; β=–0.210) and team atmosphere (B=0.158; SE(B)=0.073; p=0.034; 95%KI for B [0.012; 0.303]; β=0.180).

Table 4: Multivariate model to explain organisational commitment

Leadership training and assessment of senior midwife as a manager

On average, the participants find that the senior midwife fulfils her/his management role moderately well (M=2.01; SD=1.28, N=111). A total of 36.9% are of the view that s/he does not do their job at all well (n=16) or not very well (n=25).

The respondents do not rate managers who have completed leadership training any better (Md=2, U=633,500; p=0.563) than those who have not (Md=2, N=95; don’t know=16).

Discussion

The results are discussed separately in relation to each research objective. Subsequently the methodology is critically examined.

Perceived leadership behaviour according to the Full Range of Leadership Model

In a first step, we sought to answer the question as to the extent to which midwives observed leadership behaviour according to the Full Range of Leadership Model. On average, the midwives surveyed perceived TL among midwife managers sometimes or slightly less than sometimes (1.77IS ≤M≤2.12 IIb).

First, the assumptions of the Full Range of Leadership Model could be confirmed for this study population: the five transformational leadership dimensions (IIa, IIb, IS, IM, IC) as well as CR strongly correlate with the success factors of leadership surveyed, with perceived effectiveness of the manager EF (0.524 IM≤r≤0.843 IIa) and satisfaction with the manager SAT (0.488 IM≤r≤0.843 IC). In line with the model assumptions, LF is also highly negatively correlated with SAT (r=–0.733; p=0.000) and EF (r=–0.825; p=0.000). Hence, in the midwifery context, too, a high degree of transformational leadership behaviour and a low degree of passive leadership behaviour are desirable.

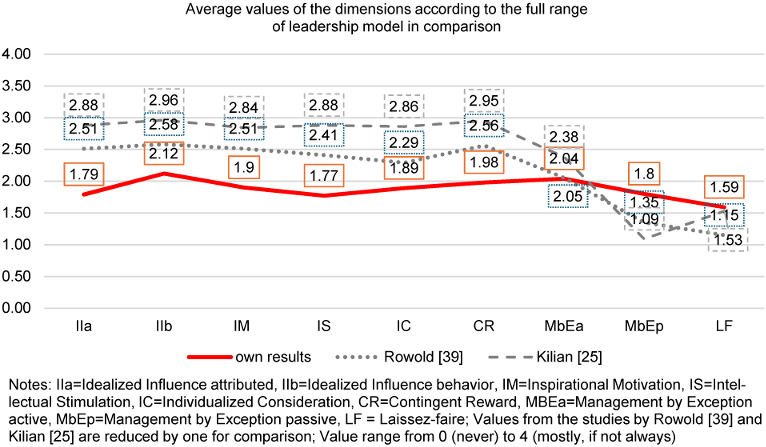

However, compared with the findings of a study examining the nursing sector [25] and the values from a cross-sector sample from Germany [39], the midwives participating in this survey reported that their managers demonstrated less transformative and more passive leadership behaviour (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]).

Figure 1: Average values of the dimensions according to the Full Range of Leadership Model compared to the findings of other studies in Germany

It is important to bear in mind that a certain degree of distortion of the findings is to be expected due to self-selection (see also Limitations).

On the other hand, there are factors which have the opposite effect, so the results for TL would have to be rather high. Because of the similarities between TL and midwifery-specific practices a rather high degree of TL is presumed among senior midwives [12]. Additionally, it can be assumed that, in this survey, both the midwife managers and the midwives being managed are predominantly women. It is well-known that women are more likely to adopt a transformational leadership style than men and that women being managed are more likely to observe transformational leadership in their managers than their male counterparts [5], [18].

Taken together, it is presumed that the lower scores for transformational leadership are not only due to self-selection bias.

The low level of TL may also be down to obstacles related to the managers’ working conditions. According to the findings of a survey by Albrecht et al. [2] only 5% of senior midwives are fully released from their regular duties to carry out their management roles. The work of the senior midwives is presumably also made more difficult due to their ‘sandwich position’ in the hospital. Midwife managers stand between the expectations and demands of the nursing management (NM), hospital management, medical direction and the midwives they manage [37]. Tasks are passed from top to bottom, which increases their workload and stress. At the same time, the leeway in this position is often very limited [7].

Under these conditions, it appears to be difficult to lead a team in accordance with TL.

Transformational leadership and organisational commitment

The second research question aims to identify a possible association between transformational leadership behaviour and the OC of the midwives, taking into account social and organisational factors.

Overall, the OC of the respondents is low (M=1.69) and is well below the average found in the study by Maier and Woschée [30] of M=2.11. (The mean value cited from the study by Maier and Woschée [30] was reduced by one here, as the scale used in their study is shifted by one to the right, so from one to five). This could be due to the distinctive feature of the hospital as an expert organisation. In this context, the skilled staff do not identify as strongly with the organisation as with their occupational group [40].

Predictors for OC are shown to be the hospital management’s support for the area of work (β=0.375; p=0.000), work-related stress (β=–0.210; p=0.011) and team atmosphere (β=0.180; p=0.034), which corresponds to the findings of other studies [2], [3], [33], [41].

An association is found between TL and OC in the bivariate analysis (r=0.343; p=0.000) which is within the range of the values of international studies from the nursing field (0.15≤r≤0.495) [4], [10]. In the last step of the multivariate analysis, however, TL no longer makes an independent significant contribution to the explanation of variance. This could be due to a low unique contribution of TL to OC as well as an insufficient sample size. Felfe [16] finds that the contribution of leadership is substantially reduced if work characteristics are also controlled for. Further, Avolio et al. [4] show that the effect of leadership on OC is higher, the larger the distance between the manager and the person being managed in the organisational hierarchy. This is in line with the finding that the hospital management’s behaviour has a greater influence in this survey than that of the senior midwives. Transformational leadership is also associated with the individual’s identification with the group’s aims, pride in the group and collective self-efficacy [6]. The effect of leadership on team spirit might be one explanation for why the significant contribution of leadership behaviour is cancelled out by the inclusion of the variable team atmosphere. Hence, the association between TL and OC could partially be mediated through team atmosphere.

Leadership training

Respondents did not rate their managers any higher when the latter had completed leadership training. This might indicate poor training effectiveness. However, in interpreting this, it is important to note that no distinction is made as to what type of leadership training has been completed and how long ago. This points to a need for further research.

Critique of methodology and limitations

The data set out on leadership represents the subjective perceptions of the participating midwives. This is useful because the success of leadership depends on the reaction of the team members to the perceived leadership behaviour. However, it is possible that the midwives in the management positions would assess their own leadership behaviour entirely differently.

The method of recruitment via digital media may be the reason for the overrepresentation of young midwives in the sample. However, this may also be because it is typical for young people at the start of their careers to want a good manager [29]. Since this the survey uses a convenience sample, distortion due to self-selection is unavoidable. This distortion may have been exacerbated within the variable of OC since midwives could still participate in the survey even if they had left the hospital they worked for. The latter criterion was applied to avoid the systematic exclusion of the group and thus a sampling bias. Lastly, recall bias is also a possibility with regards to the question of whether the manager has completed leadership training. However, this was prevented by integrating a ‘don’t know’ field into the survey.

The extent to which the findings of the study are generalisable is unclear. Presumably, however, they have some explanatory power at least for the young midwives with university degrees who are so strongly represented in the sample.

The explanatory power of the analysis is limited by the fact that the target sample size of 150 participants was not achieved. Contrary to expectations, the multivariate regression analysis did not show a significant contribution of TL, which could have been due to type II error.

It should also be noted that multiple participation in the survey could not be ruled out, due to the need to preserve participants’ anonymity.

Further, the design of the cross-sectional study does not allow for any causal statements.

Conclusions

Leadership behaviour: The present survey provides some initial insights into the leadership behaviour practiced by senior midwives in hospitals in Germany. Despite the aforementioned limitations, a low level of TL can be assumed. The findings of this study suggest that teams with midwives benefit when their managers adopt a transformational leadership style. At the same time, the high level of laissez-faire leadership as well as the finding that 36.9% of the respondents rated how their managers fulfilled their management roles as ‘not good at all’ (n=16) or barely good (n=25) show that there is a need for action.

This implies that senior midwives should seek to adopt a transformational leadership style. Here they should remember their midwifery skills and practice ‘midwifing the midwives’ ([22], p. 3). In much the same way as women receiving midwifery care are given praise and recognition, participate in joint decision-making and are helped to overcome challenges and not to lose sight of the purpose of their efforts, managers behaviour towards the midwives they are managing can follow similar principles. At the same time, one essential step would appear to be to improve the working conditions of senior midwives so that they have the capacity to lead.

Leadership and OC: The evidence presented does not allow any conclusions to be drawn as to whether TL has a positive independent effect on midwives’ OC. Based on the data, this cannot, however, be ruled out and should be explored further. Nonetheless, the calculations yield important information on how to foster OC: the findings point to the importance of senior management at the higher levels of the hierarchy. In this context, an interesting tool for hospital managers and NMs could be what is known as the ‘Gemba Walk’, which is part of the Lean Management philosophy [24]. According to this methodology, all managers are asked to occasionally leave their desks, visit staff at work and engage in conversation with them.

To reduce work-related stress, the working conditions of midwives in hospitals ought to be improved. To achieve this, the German Midwifery Association (DHV) proposes the recruitment of more midwives as well as other staff to take on telephone services or conduct cleaning tasks, for example [13].

For the senior midwives, a key starting point is the improvement of the team atmosphere. Ideas for how to achieve this are social activities with the team, inter-disciplinary case discussions and TL. Working together to overcome hurdles and to find solutions has a positive effect on groups [6].

Research: This study clearly indicates the need for further research. Future studies should be conducted using probabilistic samples with a larger number of cases. In particular, efforts should be made to reach older midwives without a university degree. This could be successfully achieved using paper questionnaires as midwives in the HebAB.NRW study indicated a preference for this format [36].

The working conditions of senior midwives also seem to be key to improving leadership. Here, qualitative research might be well suited to investigate the challenges faced by senior midwives and their understanding of their management role. Overall, the topics of leadership and OC would probably benefit greatly from the findings of qualitative research.

Thematically, the management of teams with freelance midwives or midwife-led delivery rooms were neglected in this study.

Lastly, the effectiveness of leadership training courses should also be reviewed.

Conclusion: This study makes an initial contribution to the analysis of leadership in the context of clinical midwifery. The findings lead us to conclude that there is, on the whole, room for improvement when it comes to the leadership behaviour of senior midwives and that the OC of midwives is low. With respect to the OC of midwives, hospital managers/NMs and senior midwives have the responsibility to fulfil their leadership role, reduce stress for midwives and improve the team atmosphere.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Abgeordnetenhaus Berlin. Weiterbildungs- und Prüfungsverordnung für die Heranbildung von Pflegefachkräften für leitende Funktionen vom 30. Juni 1996. Zuletzt geändert durch Artikel I des Gesetzes vom 09.11.2005. GVBl. 2005;(40):718.[2] Albrecht M, Loos S, an der Heiden I, Temizdemir E, Ochmann R, Sander M, Bock H, Schiffhorst G, Nissing M, Schlamann T, Alber V, Schiller J, Al-Abadi T. Stationäre Hebammenversorgung: Gutachten für das Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Berlin: IGES Institut; 2019. Available from: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/5_Publikationen/Gesundheit/Berichte/stationaere_Hebammenversorgung_IGES-Gutachten.pdf

[3] Alipour F, Kamaee Monfared M. Examining the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment among nurses of hospitals. Patient Saf Qual Impro. 2015;3(4):277-80. DOI: 10.22038/psj.2015.5250

[4] Avolio BJ, Zhu W, Koh W, Bhatia P. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. J Organ Behav. 2004;25(8):951-68. DOI: 10.1002/job.283

[5] Bass BM, Avolio BJ, Atwater L. The transformational and transactional leadership of men and women. Appl Psychol Int Rev. 1996;45(1):5-34. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1996.tb00847.x

[6] Bass BM, Riggio RE. Transformational Leadership. 2nd ed. Mahwah: Taylor and Francis; 2005. DOI: 10.4324/9781410617095

[7] Bergmann B. Personalmanagement im Krankenhaus: Mitarbeiterorientierung ist Chefsache. Dtsch Arztebl International. 2012;109(6):A-278/B-243/C-239.

[8] Blum K, Löffert S. Gibt es einen Hebammenmangel in Deutschland? Public Health Forum. 2021;29(2):163-5. DOI: 10.1515/pubhef-2021-0025

[9] Bode S, Bauer NH, Hellmers C. Arbeitszufriedenheit von Hebammen im Kreißsaal. Die Hebamme. 2016;29(02):118-23. DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-100785

[10] Brewer CS, Kovner CT, Djukic M, Fatehi F, Greene W, Chacko TP, Yang Y. Impact of transformational leadership on nurse work outcomes. J Adv Nurs. 2016 Nov;72(11):2879-93. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13055

[11] Bundesärztekammer. BÄK-Curriculum Ärztliche Führung. 2023. Available from: https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/BAEK/Themen/Aus-Fort-Weiterbildung/Fortbildung/BAEK-Curricula/BAEK-Curriculum_AErztliche_Fuehrung.pdf

[12] Byrom S, Byrom A, Downe S. Transformational Leadership and Midwifery: A Nested Narrative Review. In: Downe S, Byrom S, Simpson L, editors. Essential Midwifery Practice: Leadership, Expertise and Collaborative Working. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2011. p. 23-43. DOI: 10.1002/9781118784990.ch2

[13] Deutscher Hebammenverband. Die Arbeitssituation von angestellten Hebammen in Kliniken - Hebammenbefragung 2015. Karlsruhe: DGHWi; 2016. Available from: https://www.hebammen-nrw.de/cms/fileadmin/redaktion/Aktuelles/pdf/2016/DHV_Hebammenbefragung_Nov_2015_final.pdf

[14] Döring N, Bortz J. Operationalisierung. In: Döring N, Bortz J, editors. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2016. p. 221-89. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-41089-5_8

[15] Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007 May;39(2):175-91. DOI: 10.3758/bf03193146

[16] Felfe J. Transformationale und charismatische Führung - Stand der Forschung und aktuelle Entwicklungen. Z Personalpsychol. 2006;5(4):163-76. DOI: 10.1026/1617-6391.5.4.163

[17] Felfe J, Ducki A, Franke F. Führungskompetenzen der Zukunft. In: Badura B, Ducki A, Baumgardt J, Meyer M, Schröder H, editors. Fehlzeiten-Report 2014: Erfolgreiche Unternehmen von morgen - gesunde Zukunft heute gestalten. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. p. 139-48. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-43531-1_14

[18] Felfe J, Schyns B. Personality and the Perception of Transformational Leadership: The Impact of Extraversion, Neuroticism, Personal Need for Structure, and Occupational Self-Efficacy. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;36(3):708-39. DOI: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00026.x

[19] Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, Levenstein S, Klapp BF. PSQ - Perceived Stress Questionnaire [Verfahrensdokumentation aus PSYNDEX Tests-Nr. 9004426, PSQ20-Skalenberechnung, PSQ20-Fragebogen Englisch, Deutsch, Deutsch (letzte 2 Jahre)]. In: Leibniz-Zentrum für Psychologische Information und Dokumentation (ZPID), editor. Elektronisches Testarchiv. Trier: ZPID; 2009. DOI: 10.23668/psycharchives.351

[20] Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Vereinbarung über Maßnahmen zur Qualitätssicherung der Versorgung von Früh- und Neugeborenen. Fassung vom 20. September 2005, in Kraft getreten 01. Januar 2006. BAnz. 2005 Oct 28;(205):15684.

[21] Harvie K, Sidebotham M, Fenwick J. Australian midwives' intentions to leave the profession and the reasons why. Women Birth. 2019 Dec;32(6):e584-e593. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.01.001

[22] Hewitt L, Priddis H, Dahlen HG. What attributes do Australian midwifery leaders identify as essential to effectively manage a Midwifery Group Practice? Women Birth. 2019 Apr;32(2):168-77. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.06.017

[23] Jackson TA, Meyer JP, Wang XH. Leadership, commitment, and culture: A meta-analysis. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2013;20(1):84-106. DOI: 10.1177/1548051812466919

[24] Kaplan GS. Defining a New Leadership Model to Stay Relevant in Healthcare. Front Health Serv Manage. 2020;36(3):12-20. DOI: 10.1097/HAP.0000000000000077

[25] Kilian R. Transformationale Führung in der Pflege als Beitrag zur Managemententwicklung: empirische Studie zum Führungsstil von Stationsleitungen im Krankenhaus. Hamburg: Kovač; 2013. (Führung und Führungskräfte; 2).

[26] Leiner DJ. SoSci Survey (Version 3.2.21). 2019 [last accessed 2020 Nov 05]. Available from: https://www.soscisurvey.de/

[27] Leonhart R. Lehrbuch Statistik: Einstieg und Vertiefung. 2nd ed. Bern: Hogrefe; 2009. DOI: 10.1024/85797-000

[28] Löffert S, Strohbach H. Landesprojekt "Führung im Krankenhaus in Rheinland-Pfalz". Mainz: Ministerium für Soziales, Arbeit, Gesundheit und Demografie des Landes Rheinland-Pfalz; 2018.

[29] Lüthy A, Ehret T. Krankenhäuser als attraktive Arbeitgeber: Mitarbeiterkultur erfolgreich entwickeln. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2013. DOI: 10.17433/978-3-17-024416-0

[30] Maier GW, Woschée RM. Die affektive Bindung an das Unternehmen: Psychometrische Überprüfung einer deutschsprachigen Fassung des Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) von Porter und Smith (1970). Z Arb Organ. 2002;46(3):126-36. DOI: 10.1026//0932-4089.46.3.126

[31] Maier GW, Woschée RM. Organizational Commitment Questionnaire-German Version [PsycTESTSRecord]. APA PsycTests; 2002. DOI: 10.1037/t07219-000

[32] Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. HRMR. 1991;1(1):61-89. DOI: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

[33] Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnytsky L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J Vocat Behav. 2002;61(1):20-52. DOI: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

[34] Mowday RT, Steers RM, Porter LW. The measurement of organizational commitment. J Vocat Behav. 1979;14(2):224-47. DOI: 10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1

[35] Oechsler WA, Paul C. Personal und Arbeit: Einführung in das Personalmanagement. 10th ed. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter; 2018. (De Gruyter Studium). DOI: 10.1515/9783110349498

[36] Peters M, Villmar A, Schäfers R, Bauer NH. HebAB.NRW - Forschungsprojekt "Geburtshilfliche Versorgung durch Hebammen in Nordrhein-Westfalen". Abschlussbericht der Teilprojekte Mütterbefragung und Hebammenbefragung. Bochum: Hochschule für Gesundheit; 2020. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.26614.83529„

[37] Quell-Liedke S. Kreißsaalleitung: Wer? Wie? Was? Hebammenforum. 2010;11(10):850-3.

[38] Rigotti T, Holstad T, Mohr G, Stempel C, Hansen E, Loeb C, Isaksson K, Otto K, Kinnunen U, Perko K. Rewarding and sustainable healthpromoting leadership. Dortmund: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin; 2014.

[39] Rowold J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire - Psychometric properties of the German translation by Jens Rowold. Menlo Park, CA, USA: MindGarden; 2005.

[40] Rybnicek R, Bergner S, Suk K. Führung in Expertenorganisationen. In: Felfe J, van Dick R, editors. Handbuch Mitarbeiterführung: Wirtschaftspsychologisches Praxiswissen für Fach- und Führungskräfte. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2016. p. 227-37. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-55080-5_42

[41] Schmidt C, Halbe B, Wolff F. Generation Y - Wie muss das Management einer Frauenklinik den Anforderungen und Bedürfnissen einer jungen Generation entgegenkommen? Gynaekologe. 2015;48(7):528-36. DOI: 10.1007/s00129-015-3742-8

[42] Schmidt-Huber M, Hörner K, Weisweiler S. Wirksames Führungsverhalten von Oberärzten und pflegerischen Stationsleitungen unter der Lupe: Führen Pflegekräfte anders als Ärzte? ZFPG. 2015;1(3):28-43. DOI: 10.17193/HNU.ZFPG.01.03.2015-07

[43] Sfantou DF, Laliotis A, Patelarou AE, Sifaki-Pistolla D, Matalliotakis M, Patelarou E. Importance of Leadership Style towards Quality of Care Measures in Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2017 Oct 14;5(4):73. DOI: 10.3390/healthcare5040073

[44] Stahl K. WITHDRAWN: Arbeitssituation von angestellten Hebammen in deutschen Kreißsälen - Implikationen für die Qualität und Sicherheit der Versorgung. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.zefq.2016.07.005

[45] The jamovi project. Jamovi (Version 1.6). 2021 [last accessed 2021 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.jamovi.org

[46] Treier M. Personalpsychologie kompakt. Weinheim: Beltz; 2011.

[47] Tsai Y. Relationship between organizational culture, leadership behavior and job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 May 14;11:98. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-98

[48] Wagner A, Rieger MA, Manser T, Sturm H, Hardt J, Martus P, Lessing C, Hammer A; WorkSafeMed Consortium. Healthcare professionals' perspectives on working conditions, leadership, and safety climate: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Jan 21;19(1):53. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-3862-7

[49] Walenta C. Empirie der Führung. In: Heimerl P, Sichler R, editors. Strategie, Organisation, Personal, Führung. Wien: Facultas-Verlag; 2012. p. 495-532.