[Zugang zur Hebammenhilfe – die Perspektive von Frauen in Lebenslagen mit psychosozialen Belastungsfaktoren]

Heike Edmaier 1Jessica Pehlke-Milde 1

1 ZHAW School of Health Sciences, Institute of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Winterthur, Switzerland

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Frauen in belasteten Lebenslagen haben einen erhöhten Unterstützungsbedarf, nehmen aber seltener Hebammenhilfe in Anspruch. Es ist wenig über Gründe dieser Ungleichheiten bei der Inanspruchnahme aus Sicht der Frauen bekannt.

Ziele/Forschungsfrage: Die Studie analysiert Einflussfaktoren des Zugangs zur Hebammenhilfe aus Perspektive von Frauen in belasteten Lebenslagen.

Methode: Es wurden 13 leitfadengestützte Interviews mit zwei Schwangeren und elf Müttern geführt. Diese wurden inhaltsanalytisch ausgewertet. Basis für die Bildung von Kategorien stellten die Dimensionen des Frameworks für den Zugang zur Gesundheitsversorgung dar.

Ergebnisse: Aus Perspektive der befragten Frauen wird der Zugang zur Hebammenhilfe vom Zufall bestimmt und wird als Glück erfahren. Grundsätzlich ist Hebammenhilfe für die befragten Frauen mit Wohlbefinden und Zunahme der Selbstkompetenzen assoziiert. Negative Erfahrungen mit Hebammen können zum Erleben von Abweisung und Ablehnung des Versorgungsangebotes führen.

Diskussion/Schlussfolgerungen: Die mangelnde Verfügbarkeit von Hebammenhilfe für Frauen in belastenden Lebenslagen sollte garantiert werden, damit der erschwerte Zugang nicht zur Erfahrung von Ohnmacht führt.

Schlüsselwörter

Hebammenhilfe, Zugang, psychosoziale Belastungen, soziale Ungleichheit, Barrieren

Background

Poverty makes people ill. This core socio-medical paradigm plays an important role in pregnancy. Difficult life situations, marked by, for instance, socio-economic disadvantages (low income, low level of education), experiences of migration and racism are proven to be associated with health disadvantages [39], [40], [52], [61], [70], [96]. The findings of socio-epidemiological studies using the life course approach emphasise the high relevance of pregnancy as a phase with lasting impact [19], [54], [77]. Thus, difficult living conditions during pregnancy result in increased risk of pathologies and complications as well as long-term effects on the health of the child [9], [15], [46], [54], [72]. When stresses accumulate, health consequences are particularly pronounced [15], [19], [60]. According to the findings of one study of prevalence, conducted in Germany, 12.9 percent of parents with children aged 0 to 3 years face multiple psychosocial stresses [24]. These families have higher support needs and could benefit from the provision of midwifery care [4], [16], [25].

This results in opportunities for midwifery to contribute to the long-term promotion of good health. There is evidence that the work of midwives can make a decisive contribution to achieving the right to health for all women and newborns [64], [74], [75], [78]. Due to their early access and the exceptionally trusting relationships they build with the women thy care for [57], [82], midwives serve a vital role as intermediary experts providing information on more extensive, needs-based care options [75], [83]. That said, relevant international studies have clearly shown that women in life situations with psychosocial stress factors find it more difficult to access midwifery care [16], [17], [21], [22], [25], [31], [65], [66], [67], [92]. International research findings show similarities when it comes to the low level of information these women have regarding access to care [21], [31], [65], [68], passivity in navigating the healthcare system [16], [33] and a need for support in negotiating the system [16], [21], [31], [68], [65]. For women with migration experience, access is made even more difficult by language and structural barriers [12], [28], [44], [53], [54], [67], [68], [73]. Women in stressful life situations who do receive midwifery care value and appreciate it [16], [25], [53].

The state of the research in Germany reveals bottlenecks, especially when it comes to outpatient midwifery services [3], [8], [37], [47], [79]. The predominantly qualitative studies that have been conducted show that the take-up of midwifery services is strongly dependent on socio-economic status. In a quantitative longitudinal study, respondents also reported the reasons for their difficulties finding a midwife [8]. Here it is evident that women with a high level of education find it easier to secure a midwife than those with a low level of education. The general conditions within the German healthcare system during the life phase around birth, marked by fragmented services and a lack of continuity of care, appear to barriers to access [6], [37], [81]. On top of this, there is also a midwife shortage in Germany [7]. Moreover, women with a low level of education are shown to lack information on outpatient midwifery services during pregnancy [62], [88]. Women with experience of migration encounter obstacles when trying to access midwifery care, especially due to language barriers and a lack of cultural and diversity sensitivity in the healthcare system [44]. However, little research has been conducted on the factors influencing (lack of) take-up from the perspective of women in life situations with psychosocial stress factors.

Theoretical framework

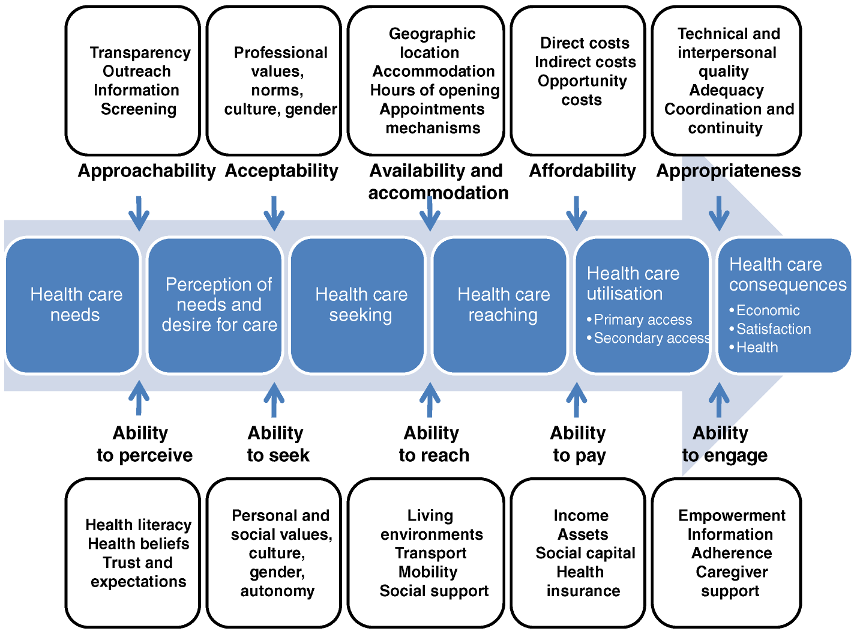

The conceptual framework on healthcare access by Levesque et al. [56] serves as the theoretical framework for the present study. The framework conceptualises access as an active process which begins with the presence of a healthcare need and then continues with the ability to perceive the need, seek, reach, and engage in healthcare, ideally culminating in an improvement in health status (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). As well as looking at the different aspects influencing the dimensions on the side of the healthcare system and on the side of the user, the framework also focuses on the interaction between these dimensions.

Figure 1: A conceptual framework of access to health care by Levesque et al. [56], licensed under CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

Aim and research question

The aim of the study is to examine the experiences and perspectives of women in stressful life situations with regard to their access to midwifery care. In so doing, the study seeks to better understand the reasons for the decision to (not) use midwifery services. The study seeks to answer the following research question: what factors influence access to midwifery care in Germany from the perspective of women in life situations with psychosocial stress?

Methodology

Design

To answer the research question, we opted for a qualitative design with semi-structured interviews. This method allows a deeper insight into subjective views, desires, needs and conditions [27]. In the call for participation in the study, women were approached who were, at the time, either pregnant or had given birth in the previous 12 months and found themselves in life situations that they described as stressful. In addition to the recruitment of women via notices and announcements on social media, the author drew on the contacts in her professional network as a family midwife. Midwives were also approached as intermediaries via the information channels of the German Midwifery Association. Informed interested parties were asked to contact us by e-mail or phone. Informed written consent was obtained before the interview was conducted.

Sampling

The target group for the present study comprised women in life situations with psychosocial stress factors. This refers to women who are exposed to psychological and social influences at the structural, family and/or individual level, which can put strain on and overwhelm these women’s resources [34], [76], [90]. These stress factors can be perceived in many ways. The literature addresses frequently mentioned aspects such as low income, low level of educational attainment, single parenthood, unemployment, migration-related stress, chronic illness, experiences of racism and experiences of discrimination based on sexual orientation [20], [23], [59]. Inclusion criteria for study participation were, in addition to the presence of at least one of the aforementioned aspects perceived as stress factors, that the woman was currently 20 weeks pregnant or more or that she had given birth in the last 12 months. When planning the sampling process, we sought to achieve heterogeneity of the women surveyed according to the principle of variance maximisation [45], [71], [85]. The sample is therefore intended to be criteria-driven, based on a strategy of purposeful sampling [84].

Data collection

The data was collected by means of semi-structured interviews, for the design of which we drew on elements of the problem-centred interview method proposed by Witzel [98]. The interview guide used was based on the framework developed by Levesque et al. [56]. In line with the principle of openness in qualitative research, in the first part of the interview, a narrative impetus was provided ([36], p. 21), [72]. The rest of the interview comprised guided, narrative-generating questions geared towards the topic of the research question [98]. To reflect on the interview situation and on her own position in the interaction, the author added a postscript as a memo shortly after each of the interviews [97]. She was also transparent, informing the interviewee of her dual role as a midwife and researcher. She accentuated the latter role, explaining that she was not conducting the interviews as a potential provider of midwifery services but rather out of an interest in the standpoint of the participants.

Ahead of this research project, on 23 July 2021, we applied for ethical approval from the Ethics Commission of the German Society for Nursing Science. This was granted on 26 August 2021 (No. 21-019).

Analysis

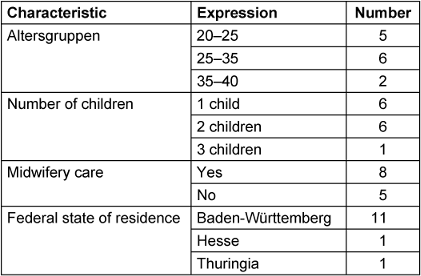

The current study used an interpretive hermeneutic design oriented towards the stepwise approach to qualitative content analysis for structuring content as described by Schreier [86]. This enabled targeted identification and conceptualisation of selected content-related aspects, while maintaining an open mind for new insights ([86], p. 5–7). The interviews were digitally recorded and promptly transcribed verbatim. They were then evaluated to determine the importance of the content ([50], p. 56). To begin with, the author created case summaries and memos ([50], p. 59) to familiarise herself with the data material [84]. She then deductively developed superordinated categories, geared towards the dimensions of the framework developed by Levesque et al. [56]. Next coding units were determined. In the interplay between deductive and inductive analytical steps, the system of categories was differentiated and tested [86]. In the process, one content-related aspect was identified as a top-level category, and the system of categories was modified accordingly [86]. Lastly, the data material was coded using the differentiated system of categories [86], ([51], p. 43ff.). The entire process of analysis was computer-assisted using MAXQDA software [94]. To assure the quality of the study, the author reflected on her own preconceptions throughout the research process. A discursive form of establishing traceability of the analytical process took place at regular meetings with the second author. From October 2021 to February 2022, n=13 semi-structured interviews were conducted. Table 1 [Tab. 1] presents the socio-demographic factors of the women interviewed (n=13).

Table 1: Socio-demographic data regarding interview participants

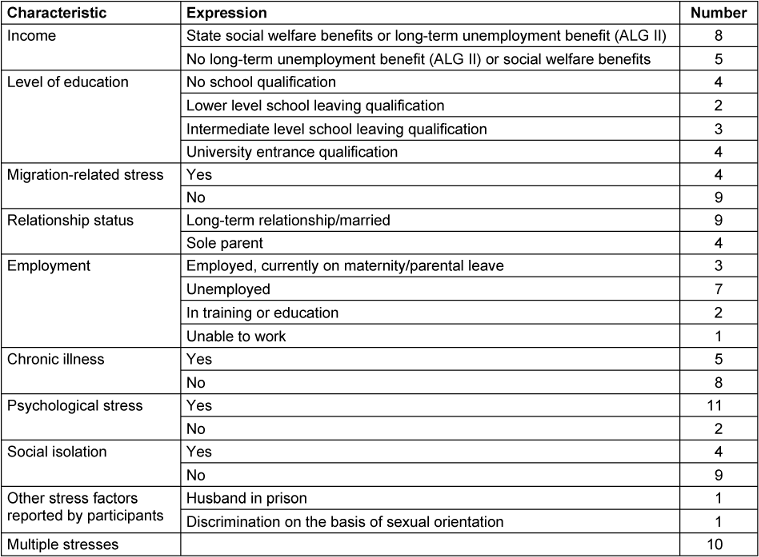

Table 2 [Tab. 2] displays the stress factors identified in the literature and subjectively reported by the respondents.

Table 2: Socio-demographic factors of participants which could point towards psychosocial stress

Results

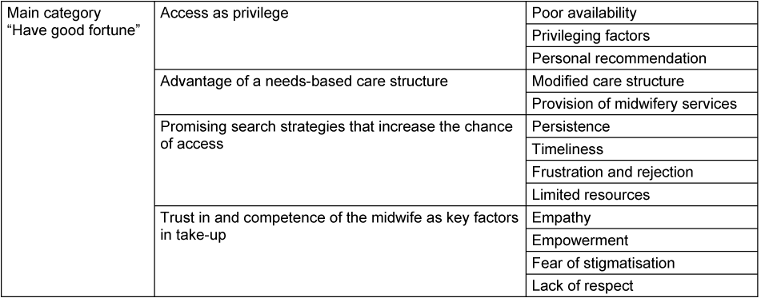

The women surveyed see access to midwifery care as primarily determined by good fortune. This is reflected in privileges, a needs-based care structure, successful search strategies as well as a personal relationship with the midwife. Good fortune is perceived as a supporting factor, which reshapes the different dimensions of access and is seen by the interviewees as an important aspect in access to midwifery care. For some of the women interviewed, good fortune serves as a constant narrative element in their access to midwifery care. The results are classified based on the categories presented in Table 3 [Tab. 3].

Table 3: Final system of categories

Access as a privilege

From the perspective of women facing psychosocial stress, access to midwifery services is influenced by personal recommendations, social networks and contact with a particular midwife. This can result in access being perceived as “a great privilege” (Philis, l. 108). The women we interviewed repeatedly referred to the poor availability of midwives. As a result, even though they would like to receive midwifery care, they often cannot find a midwife.

Philis, who has an isolated life and was unable to find a midwife, reports:

Unfortunately, I don’t think we can take midwifery care for granted. I see having access to such services as a great privilege (Philis, l. 106–8).

According to Philis, in her region you can only find a midwife if you start looking early and preferably if someone personally recommends you.

By week 6 or 7, you will only get a midwife if you have a personal referral. And the midwife has to trust the referral made by your friend, because she has already cared for several of this friend’s children or something (Philis, l. 220–2).

Philis is of the opinion that not all women have the same access to midwifery services. Personal recommendations can play a role in enabling this access. This inequality can cause frustration and disappointment at the lack of support and, in Philis’ case also exacerbated her social isolation.

When it came to access to midwifery care, Ruth, 33, was at something of an advantage. After resigning from her job as a research associate, she found herself in a difficult situation and, because of the stress she was under, was unable to look for a midwife in time. Despite the “chronic shortage of midwives” (Ruth, l. 205) in her region, she was then “really, really, really lucky!” (l. 207). For Ruth, the fact that she was acquainted with a midwife and the fact that, as she was having her second child, the midwife felt she would require less care, put her at an advantage.

She explained:

[…] when I was feeling really bad, I couldn’t do anything […] somehow I just had other worries. And then I just called the midwife, and she said yes [...], she would be happy to take me on. Erm, because she already knows me and because it’s often not as much work with second children. Erm, everything’s not quite as new as it is with a firstborn. And that’s why she was still willing to take me on (Ruth, l. 5,863)

The results suggest that the care shortage can increase barriers to midwifery services thus resulting in unequal access. This means that women in challenging life situations due to limited resources along with inadequate availability of midwives may not have appropriate access and thus find themselves in a disadvantaged position.

Advantage of a needs-based care structure

The good fortune described by some of our interlocuters was not the result of chance but rather of a care structure based on targeted outreach. Some of the women we interviewed saw this modification to the services available as beneficial. Nesrin, a Syrian immigrant, described the provision of midwifery consultation services in refugee accommodation as good fortune:

And I know the midwife who supported me four years ago which is why I found a midwife. […] From the camp. That was lucky – because of the camp. After that, everyone knew a midwife in Germany (Nesrin, l. 76–8).

Carla, on the other hand, was not so lucky when it came to accessing midwifery care. As an immigrant with limited knowledge of the German healthcare system, she was not informed about midwifery services in time.

So late, I was late, so late! I was already in my 9th month! Because I just didn’t know about it. […] It all went wrong! […] Nobody told me that I needed a midwife […]. (Carla, l. 157–61)

For women struggling financially, it is difficult to access outpatient midwifery services if having their own car is a prerequisite. Philis told us about the services of a postpartum outpatient clinic:

But I simply couldn’t get there. Because we haven’t got a car and it’s just too far away. (Philis, l. 305–6)

Outreach care provided by midwives, facilitated by interdisciplinary cooperation, can promote accessibility for women in such stressful situations.

Due to difficulties in establishing a relationship with her newborn after birth, Chantal, who was unable to find a midwife during her pregnancy, was assigned a family midwife by the hospital staff. She describes this kind of access as “a blessing in disguise” (Chantal, l. 66). The support provided helped her to deal with her feeling of being overwhelmed.

Everything was just so new! If I’m honest, we were a bit overwhelmed by everything from the very start. (Chantal, l. 96–7)

Sophia, too, would have found being provided with a midwife beneficial. During pregnancy, she was “…much more concerned about using drugs” (Sophia, l. 205).

I was, erm, a drug addict […] And because of that, I had a lot of appointments with drug counselling services, motivational groups, the child welfare office [...]. [...]. If I had had a midwife, she could have told me the best things to do in pregnancy. Maybe she could have talked me into doing something sensible. (Sophia, l. 47–8; 232–4)

When it comes to facilitating midwifery care, it is beneficial for this to be voluntary and participatory in nature. If midwifery services are imposed on a woman, this can lead to disempowerment and discomfort. Possibly under the influence of social norms, many of the women we interviewed attached great value to their autonomy and self-determination.

Wendy, a 23-year-old multigravida, was deprived of her autonomy. She was assigned a family midwife against her wishes. She wanted to overcome the challenges on her own to show her strength and capabilities. Wendy expressed the wish to go through her pregnancy and labour without external support.

But then I said: well, I managed it with Anton, my oldest, without a midwife. So I’ll manage it again this time, too. But they were all against it. They were all so eager, they really insisted that I have someone. (Wendy, l. 232–5)

[...] that was my stubbornness [...] I wanted to try to do it on my own first, […] just to show that I could! (Wendy, l. 380)

Promising search strategies that increase the chance of access

Our interviewees’ access to midwifery care was influenced by various search strategies. This search is characterised by fierce competition, and successful strategies as well as self-initiated activities increase the chance of a woman accessing suitable care. Ena, a 23-year-old primagravida, was well informed about the midwifery services in her region. She put the rejections she received from midwives down to their high workload and selected a successful strategy.

So, you’ve got a [positive pregnancy] test! Sign up straight away! Don’t even wait a week! (Ena, l. 401–2).

Because you’ll get a lot of rejections. […], just because they’re so overworked. […] I was extremely lucky! (Ena, l. 147–8).

Determination and persistence in the search for a midwife can lead to a successful outcome. Pia, a 29-year-old secundigravida, who was unable to work due to health issues, described her tenacity in her search for a midwife:

I simply didn’t give up. I just kept on calling. (Pia, l. 107)

Pia showed a very determined and proactive approach which suggests that she believed her efforts would result in success.

Well, I’ve heard from lots of women that it can’t be that easy. But I think, I just thought ‘if you stick at it and stay stubborn, you’re bound to find one!’ […] And that’s something I’m really good at! (laughs) Being stubborn! (Pia, l. 299–301)

To choose successful search strategies, women need resources for self-activation in order to cope with a long and exhausting search. Difficult financial circumstances can result in women having no resources to take care of their own needs and participate in the competition for a midwife. Maria, on her fourth child, whose husband was sent to prison when she was pregnant, tells us about her situation:

I had other things on my plate because my husband had to go away when I was pregnant, and I basically had to do everything by myself. I had to organise everything. Financially, I had totally reached my limits, I’ll tell you now. (Maria, l. 18–20)

For some of our interviewees, their search strategies proved unsuccessful. This can lead to frustration, resignation and a feeling of rejection.

Chantal had expected the search to easier and had hoped she would be able to get to know her midwife personally. Once she realised that the search was more complicated than anticipated, she gave up and resigned herself to not having a midwife.

I thought it would be […] quite different to this. I thought I’d just have to ring a few [midwives] and they’d come round for a coffee and whichever one I liked most, I’d take. But unfortunately it was nothing like that. (Chantal, l. 281–3)

…we were really actively searching. (Chantal, l. 217)

Yes – at some point I just said: ‘OK then – if no one wants me, I’ll just leave it. (Chantal, l. 54–5)

Trust in and competence of the midwife as key factors in take-up

For the interviewees, the midwife herself played an important role. Empathy and trust promote the acceptance of midwifery services, whereas a lack of empathy can be a barrier. Chantal expresses it as follows:

[...] and if I don’t like her, I can’t develop any trust in her. Then I would think, no, I’d rather not have one at all. (Chantal, l. 292–94)

The unique vulnerability and intimacy of the reproductive years are the reasons a relationship of trust with the midwife is so important. This is Ena’s view, who told us about her feelings of shame when we interviewed her:

[...] you really have to feel comfortable with this woman! […]. Because […] she is going to see you at the end of your tether, unshowered and all sorts. And just so exhausted. And she will constantly see you naked from the waist up. […] and so you really have to feel at ease with this woman! (Ena, l. 409–16)

Shame and the fear of being stigmatised by the midwife may impede access to midwifery care. Because of her drug abuse, Sophia had already experienced stigmatisation, which meant that shame became a barrier for her to even turn to a midwife.

I think that was also more of a feeling of shame […], erm, I guess, I thought that she thought [...], for me as a mother to use drugs, erm, ‘how awful!’ and ‘How can a mother do something like that? (Sophia, l. 217–9)

When it comes to acceptance, it is important that the individual has the option of choosing their midwife and shaping the range of services they receive.

Many of the women we interviewed spoke about the supportive and health-promoting effects of midwifery care. Particular emphasis was placed on how talking to a midwife can reduce anxiety thus resulting in relaxation and improved health. This was something Eva, who had experienced discrimination within her family due to her sexual orientation, also spoke about:

I was really lucky that I had such a great midwife where I lived. She also helped with discussions. She talked to us, to my father-in-law and really made a big contribution to it working so well. And I think it was because of this that my labour went so smoothly. Also, I was more relaxed. (Eva, l. 31–4)

Chantal emphasises that the way the midwife worked met her needs perfectly and that it helped her feel strong and empowered when it came to her own capabilities.

[...] she always gave me a lot of confidence that I could handle the little one. She said that we would look back on this and laugh, and she was right (laughing). (Chantal, l. 393–5)

The midwife’s psychosocial competencies are vital for the provision of appropriate care. Some of our respondents had feelings of powerlessness and low self-esteem. Disrespectful care can reinforce these feelings. A lack of respect and discrimination in the obstetric context can diminish self-confidence and trust in midwifery care which is a big challenge for the women effected. Canan told us about the traumatic experiences she faced when giving birth to her first child, including physical and psychological violence on the part of midwife. Now she is reluctant to opt for midwifery care in her second pregnancy:

I would just like to feel comfortable with her. [...] I had something of a traumatic labour. [...], because the midwife treated me really, really, really badly. So, it was, [...] I mean I still haven’t fully processed it yet. (Canan, l. 252–5)

Discussion

The current study presents heterogenous experiences of and views on access to midwifery care from the perspective of women in life situations with psychosocial stress. The gaps in care described by various different studies [3], [8], [47], [79] have resulted in these women struggling to access midwifery services and thus experiencing uneven distribution of access to opportunities. This, in turn, leads to noticeable inequality and gives rise to frustration, powerlessness and feelings of rejection.

Given the legal obligation of the German state to ensure access to healthcare [18], there is an urgent need for action, which has already been identified by a number of studies [5], [8]. We need to develop a system of care which is suited to the limited possibilities of people in stressful life situations. The findings of these studies suggest that outreach midwifery work, and not only in refugee accommodation, can improve access to midwifery care for people with experience of migration [24], [30], [79], [87]. This also applies to other specialised institutions geared towards target groups with specific needs, such as addiction advice centres.

As already shown in other studies, effective coordination at interfaces and interdisciplinary collaboration can improve targeted support for families in stressful situations [11], [26], [52]. It is important that when designing midwifery services their voluntary and participatory nature are emphasised. Specific access to midwifery services by means of selective allocation instead of self-selection processes risks stigmatisation and restriction of autonomy [29], [93]. In contrast to other research [16], [33], the data from this study provides hardly any evidence of passive behaviour of women when it comes to navigating the healthcare system. Some women even report having a very high level of dedication and well thought-out strategies to find a midwife. However, the opportunities people have to use healthcare services are determined by social living conditions [1]. Similarly, these women are subject to certain restrictions when it comes to perception of care needs. This is because women in certain living situations cannot afford [49], [55] some of actions required to access care, as described by Levesque et al. [56]. For example, difficult financial circumstances, limited mobility, psychological stress or addiction limit the use of midwifery services. Overall, the study shows, in line with other sources [38], [39], that, due to the complex interaction of social circumstances and psychological well-being, the experiences of people in stressful life situations are highly individual.

Consistent with other studies [8], [62], [75], here too the women interviewed had a fundamentally positive view of the provision of midwifery care and associated it with descriptions of good fortune. The study findings emphasise the importance of the role of the midwife herself for the acceptance and effectiveness of midwifery services. Empathy, trust, sensitivity to diversity and respectful, compassionate care are key factors in the well-being of the women. And it is precisely these aspects that Renfrew et al. [74] identified as evidence-based components of effective care provision for mothers and newborns. Not only the structure of the working alliance, but also the quality of the relationship with the midwife has a direct impact on both the take-up and effectiveness of midwifery services [13], [82], [99]. In line with other studies [10], [58], [96] the current data also show that experiences of discrimination in midwifery care can lead to a sense of rejection and not being supported. Such experiences can be an obstacle to women’s acceptance of care services and may even contribute to these services being rejected entirely.

In keeping with other studies [14], [32], [43], we find significant opportunities for working with women facing psychosocial stresses. Through a practice of empowerment, a higher level of health-promoting self-competence could be achieved. According to Van Staa and Renner [93], imposed midwifery care can have a patronising character and be accompanied by potential stigmatisation and the woman rejecting the services.

As in the study by Simon [89], our findings show that a midwife’s psychosocial competencies make a significant contribution to the acceptance and adequacy of care and thus promote take-up. On the other hand, the results of numerous international studies find that midwives providing outpatient care often do not feel sufficiently competent in dealing with the women’s psychosocial problems [35], [42], [63], [67], [89].

The findings highlight the importance of midwives having communicative competencies, as emphasised by Pehlke-Milde [69]. Similar to Kraus ([48], p. 68ff.), the women surveyed reported that such communication skills create a positive enabling atmosphere. This can reduce internal barriers to take-up of midwifery services and increase the benefits.

The current study provides a comprehensive view of the complex process of access from the perspective of women in situations with psychosocial stress. Despite the challenge of reaching target groups [2], [11], [41], [95] that are “rarely heard” [80], we managed to conduct 13 interviews with the target group under study. This can be considered one of the study’s strengths. For the most part, the women interviewed were very open and trusting in sharing their views and experiences. The rich results provided useful insights from which we were able to derive conclusions for the organisation and design of care services and future research. Limitations arose primarily due to the way in which participants were recruited. It can be assumed that the form of recruitment via a gatekeeper and the fact that the interviews were conducted by a researcher who herself was also a qualified midwife led to socially desirable responses.

Conclusions

The barriers to midwifery care for women with complex psychosocial needs identified in the study and the perceived inequality imply a need for action to prevent powerlessness and discrimination.

In addition to ensuring sufficient available midwife capacity, targeted optimisation of the care structure requires effective concepts which take the needs and challenges of these women into account. Examples of established care concepts in municipal structures are midwifery agencies [47] and outreach midwifery work in refugee accommodation. In some Swiss cantons, midwife networks such as Familystart [30] have been established, which specifically provide midwifery services to families and ensure guaranteed provision of care. One example of extended support is the evaluated Swiss model “SORGSAM – Support am Lebensstart” [87], which extends the services provided by Familystart and as an early intervention programme recognises the significant role played by midwives as important points of contact for families with complex psychosocial needs. The care model offers these families improved support from midwives who are continuously trained in family-centred counselling, as well as a hardship fund for services not covered by health insurance and emergency financial assistance. The model is offered in collaboration with the Basel section of the Swiss Association of Midwives and co-financed by the Basel City Health Department. Another way of optimising accessibility for women who already have contact with social services due to mental health problems, could be strengthened intersectoral cooperation between the healthcare system and social services. Important factors for the acceptance of midwifery care are its voluntary and participatory nature. Women should be able to choose their own midwives and participate in the process of care provision. To meet the needs of families facing psychosocial stress and prevent disrespect, sensitivity to diversity and appropriate communication skills must be embedded in the development of the curricula for midwifery degrees and further training. Future research would be well placed to focus on diversity competencies and the practice of midwives in providing care for women with psychosocial stress.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Abel T, Sommerhalder K. Gesundheitskompetenz/Health Literacy: Das Konzept und seine Operationalisierung [Health literacy: An introduction to the concept and its measurement]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015 Sep;58(9):923-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-015-2198-2[2] Aglipay M, Wylie JL, Jolly AM. Health research among hard-to-reach people: six degrees of sampling. CMAJ. 2015 Oct;187(15):1145-9. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.141076

[3] AOK. Gesunder Start ins Leben. Schwangerschaft – Geburt – erstes Lebensjahr. Düsseldorf: AOK Rheinland/Hamburg; 2018. Available from: https://www.aok.de/pk/magazin/cms/fileadmin/pk/rheinland-hamburg/pdf/report-gesunder-start-ins-leben-2018.pdf

[4] Ayerle GM, Makowsky K, Schücking BA. Key role in the prevention of child neglect and abuse in Germany: continuous care by qualified family midwives. Midwifery. 2012 Aug;28(4):E469-77. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.05.009

[5] Ayerle GM, Mattern E. Prioritäre Themen für die Forschung durch Hebammen: Eine Analyse von Fokusgruppen mit schwangeren Frauen, Müttern und Hebammen. GMS Z Hebammenwiss. 2017;4:Doc04. DOI: 10.3205/zhwi000010

[6] Ayerle GM, Mattern E, Lohmann S. Kirchner Hebammenversorgung: "Ich wünsche mir...". Präferenzen und Defizite in der hebammenrelevanten Versorgung in Deutschland aus Sicht der Nutzerinnen und Hebammen: Eine qualitative explorative Untersuchung. 2017. Available from: https://www.umh.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Dokumente/Institut_GPW/Forschung/Projektbeschreibungen/Projektbeschreibung_Hebammenversorgung.pdf

[7] Bauer N, Blum K, Löffert S, Luksch K. Handlungsempfehlungen zum "Gutachten zur Situation der Hebammenhilfe in Hessen": Gutachten des Deutsches Krankenhausinstitut (DKI) und der Hochschule für Gesundheit (hsg) Bochum, StB Hebammenwissenschaft für das Hessische Ministerium für Soziales und Integration (HSMI). Bochum/Düsseldorf: DKI & hsg; 2020.

[8] Bauer NH, Schäfers R, Peters M, Villmar A. HebAB. NRW - Forschungsprojekt "Geburtshilfliche Versorgung durch Hebammen in Nordrhein-Westfalen". Abschlussbericht der Teilprojekte Mütterbefragung und Hebammenbefragung. Bochum: Hochschule für Gesundheit Bochum; 2020.

[9] Benarous X, Raffin M, Bodeau N, Dhossche D, Cohen D, Consoli A. Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Inpatient Youths with Severe and Early-Onset Psychiatric Disorders: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2017 Apr;48(2):248-59. DOI: 10.1007/s10578-016-0637-4

[10] Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, Aguiar C, Saraiva Coneglian F, Diniz AL, Tunçalp Ö, Javadi D, Oladapo OT, Khosla R, Hindin MJ, Gülmezoglu AM. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2015 Jun;12(6):e1001847; discussion e1001847. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

[11] Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, Chapman K, Twyman L, Bryant J, Brozek I, Hughes C. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014 Mar;14:42. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-42

[12] Bradby H, Humphris R, Newall D, Phillimore J. Public Health Aspects of Migrant Health: A Review of the Evidence on Health Status for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2015. (Health Evidence Network synthesis report; 44).

[13] Bradfield Z, Duggan R, Hauck Y, Kelly M. Midwives being 'with woman': An integrative review. Women Birth. 2018 Apr;31(2):143-52. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.07.011

[14] Connelly LM, Keele BS, Kleinbeck SV, Schneider JK, Cobb AK. A place to be yourself: empowerment from the client's perspective. Image J Nurs Sch. 1993;25(4):297-303. DOI: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00263.x

[15] Crandall A, Miller JR, Cheung A, Novilla LK, Glade R, Novilla MLB, Magnusson BM, Leavitt BL, Barnes MD, Hanson CL. ACEs and counter-ACEs: How positive and negative childhood experiences influence adult health. Child Abuse Negl. 2019 Oct;96:104089. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104089

[16] Darling EK, Grenier L, Nussey L, Murray-Davis B, Hutton EK, Vanstone M. Access to midwifery care for people of low socio-economic status: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Nov;19(1):416. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-019-2577-z

[17] Dawson AJ, Nkowane AM, Whelan A. Approaches to improving the contribution of the nursing and midwifery workforce to increasing universal access to primary health care for vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2015 Dec;13:97. DOI: 10.1186/s12960-015-0096-1

[18] Deutscher Bundestag. Grundgesetzlicher Anspruch auf gesundheitliche Versorgung. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag; 2015.

[19] Dravta J, Grylka-Bäschlin S, Volken T, Zyssen A. Wissenschaftliche Übersichtsarbeit frühe Kindheit (0-4j.) in der Schweiz: Gesundheit und Prävention. Winterthur: Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften ZHAW; 2019.

[20] Dudenhausen JW, Kirschner R. Psychosoziale Belastungen als Risikofaktoren der Frühgeburt--Erste Befunde der Daten des BabyCare-Projekts [Psychosocial stress as a risk factor for preterm birth--first results of the BabyCare project]. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2003;125(3-4):112-22. DOI: 10.1055/s-2003-41907

[21] Ebert L, Bellchambers H, Ferguson A, Browne J. Socially disadvantaged women's views of barriers to feeling safe to engage in decision-making in maternity care. Women Birth. 2014 Jun;27(2):132-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2013.11.003

[22] Economidoy E, Klimi A, Vivilaki VG. Caring for substance abuse pregnant women: The role of the midwife. Health Sci J. 2012;6(1):161-9.

[23] Ehlert U. Einfluss von Stress auf den Schwangerschaftsverlauf und die Geburt. Psychotherapeut. 2004;49:367-76. DOI: 10.1007/s00278-004-0389-7

[24] Eickhorst A, Schreier A, Brand C, Lang K, Liel C, Renner I, Neumann A, Sann A. Inanspruchnahme von Angeboten der Frühen Hilfen und darüber hinaus durch psychosozial belastete Eltern [Knowledge and use of different support programs in the context of early prevention in relation to family-related psychosocial burden]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016 Oct;59(10):1271-80. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-016-2422-8

[25] Fair F, Raben L, Watson H, Vivilaki V, van den Muijsenbergh M, Soltani H; ORAMMA team. Migrant women's experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity care in European countries: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228378. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228378

[26] Fischer J, Geene R. Gelingensbedingungen der Kooperation von Kinder- und Jugendhilfe und Gesundheitswesen: Handlungsansätze und Herausforderungen im Kontext kommunaler Präventionsketten. Düsseldorf: Forschungsinstitut für gesellschaftliche Weiterentwicklung e.V. (FGW); 2019. (FGW-Impuls Vorbeugende Sozialpolitik; 19).

[27] Flick U, von Kardorff E, Steinke I. Was ist qualitative Forschung? Einleitung und Überblick. In: Flick U, von Kardoff E, Steinke I, editors. Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch. 14th ed. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch; 2000. p. 13-9.

[28] Gewalt SC, Berger S, Ziegler S, Szecsenyi J, Bozorgmehr K. Psychosocial health of asylum seeking women living in state-provided accommodation in Germany during pregnancy and early motherhood: A case study exploring the role of social determinants of health. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208007. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208007

[29] Grieshop M, Tegethoff D, Streffing J. Stigmatisierung versus Unterstützung von Eltern - der Erstzugang zu jungen Familien im Kontext der Frühen Hilfen. In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hebammenwissenschaft, editor. 5. Internationale Konferenz der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Hebammenwissenschaft (DGHWi). Bochum, 13.-14.02.2020. Düsseldorf: German Medical Science GMS Publishing House; 2020. Doc20dghwiP07. DOI: 10.3205/20dghwi23

[30] Grylka-Baeschlin S, Iglesias C, Erdin R, Pehlke-Milde J. Evaluation of a midwifery network to guarantee outpatient postpartum care: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Jun;20(1):565. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-020-05359-3

[31] Haddrill R, Jones GL, Mitchell CA, Anumba DO. Understanding delayed access to antenatal care: a qualitative interview study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 Jun;14:207. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-207

[32] Halldorsdottir S, Karlsdottir SI. The primacy of the good midwife in midwifery services: an evolving theory of professionalism in midwifery. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011 Dec;25(4):806-17. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00886.x

[33] Hänelt M, Renner I. Unterstützungsbedarf von Müttern in Belastungslagen rund um die Geburt. Hebamme. 2021;34:39-46. DOI: 10.1055/a-1644-7453

[34] Hasler M, Magklara K, von Wyl A, Zollinger R. Psychosoziale Belastungsfaktoren in der Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie - eine retrospektive Studie. Schweiz Med. 2012;12(42):819-20. DOI: 10.4414/smf.2012.01288

[35] Hauck YL, Kelly G, Dragovic M, Butt J, Whittaker P, Badcock JC. Australian midwives knowledge, attitude and perceived learning needs around perinatal mental health. Midwifery. 2015 Jan;31(1):247-55. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2014.09.002

[36] Helfferich C. Die Qualität qualitativer Daten: Manual für die Durchführung qualitativer Interviews. 4th ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2010. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-531-92076-4

[37] Hertle D, Lange U, Wende D. Schwangerenversorgung und Zugang zur Hebamme nach sozialem Status: Eine Analyse mit Routinedaten der BARMER [Healthcare in Pregnancy and Access to Midwives according to Socio-Economic Situation: An Analysis with Routine Data from BARMER Health Insurance]. Gesundheitswesen. 2023 Apr;85(4):364-70. DOI: 10.1055/a-1690-7079

[38] Hobfoll SE. Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol. 2002;6(4):307-24. DOI: 10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

[39] Hoebel J, Lampert T. Subjective social status and health: Multidisciplinary explanations and methodological challenges. J Health Psychol. 2020 Feb;25(2):173-85. DOI: 10.1177/1359105318800804

[40] Janβen C, Frie KG, Dinger H, Schiffmann L, Ommen O. Der Einfluss von sozialer Ungleichheit auf die medizinische und gesundheitsbezogene Versorgung in Deutschland. In: Richter M, Hurrelmann K, editors. Gesundheitliche Ungleichheit. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2009. p. 141-55. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-531-91643-9_8

[41] Johnston LG, Sabin K. Sampling Hard-to-Reach Populations with Respondent Driven Sampling. Methodol Innov Online. 2010;5(2):38-48. DOI: 10.4256/mio.2010.0017

[42] Jones CJ, Creedy DK, Gamble JA. Australian midwives' awareness and management of antenatal and postpartum depression. Women Birth. 2012 Mar;25(1):23-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2011.03.001

[43] Jones PS, Meleis AI. Health is empowerment. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1993 Mar;15(3):1-14. DOI: 10.1097/00012272-199303000-00003

[44] Kasper A. Geburtshilfliche Versorgung von Frauen mit Fluchterfahrung. In: Die geburtshilfliche Betreuung von Frauen mit Fluchterfahrung: Eine qualitative Untersuchung zum professionellen Handeln geburtshilflicher Akteur*innen. Wiesbaden: Springer; 2021. p. 33-44. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-658-33413-0_4

[45] Kelle U, Kluge S. Verfahren der Fallkontrastierung I: Qualitatives Sampling. In: Vom Einzelfall zum Typus: Fallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. 2nd edition. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2010. p. 41-55. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-531-92366-6_4

[46] Kim HW, Jung YY. [Effects of antenatal depression and antenatal characteristics of pregnant women on birth outcomes: a prospective cohort study]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012 Aug;42(4):477-85. DOI: 10.4040/jkan.2012.42.4.477

[47] Kohler S, Bärnighausen T. Entwicklung und aktuelle Versorgungssituation in der Geburtshilfe in Baden-Württemberg - Bericht für den Runden Tisch Geburtshilfe in Baden-Württemberg. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Institut für Global Health; 2018.

[48] Kraus B. Erkennen und Entscheiden: Grundlagen und Konsequenzen eines erkenntnistheoretischen Konstruktivismus für die Soziale Arbeit. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa; 2013.

[49] Kraus B. Systemisch-konstruktivistische Lebensweltorientierung. Familiendynamik. 2016;41(3):188-96.

[50] Kuckartz U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. 3rd ed. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa; 2016.

[51] Kuckartz U, Rädiker S. Fokussierte Interviewanalyse mit MAXQDA: Schritt für Schritt. Wiesbaden: Springer VS; 2020. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-658-31468-2

[52] Lampert T, Kroll LE, Kuntz B, Hoebel J. Health inequalities in Germany and in international comparison: trends and developments over time. J Health Monit. 2018;3(Suppl 1):1-24. DOI: 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-036

[53] Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. 'Not enough people to look after you': an exploration of women's experiences of childbirth in the Republic of Ireland. Midwifery. 2012 Feb;28(1):98-105. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.11.007

[54] Larrañaga I, Santa-Marina L, Molinuevo A, Álvarez-Pedrerol M, Fernández-Somoano A, Jimenez-Zabala A, Rebagliato M, Rodríguez-Bernal CL, Tardón A, Vrijheid M, Ibarluzea J. Poor mothers, unhealthy children: the transmission of health inequalities in the INMA study, Spain. Eur J Public Health. 2019 Jun;29(3):568-74. DOI: 10.1093/eurpub/cky239

[55] Leßmann O. Lebenslagen und Verwirklichungschancen (capability) - Verschiedene Wurzeln, ähnliche Konzepte. Vierteljahrsh Zur Wirtsch. 2006;75(1):30-42. DOI: 10.3790/vjh.75.1.30

[56] Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013 Mar;12:18. DOI: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

[57] Lewis M. Trust me I am a midwife. Int J Integr Care. 2019;19:307. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.s3307

[58] Limmer C, Striebich S, Tegethoff D, Jung T, Leinweber J; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hebammenwissenschaft (DGHWi). Respektlosigkeit und Gewalt in der Geburtshilfe. GMS Z Hebammenwiss. 2020;7:Doc05. DOI: 10.3205/zhwi000019

[59] Lorenz S, Ulrich SM, Sann A, Liel C. Self-Reported Psychosocial Stress in Parents With Small Children. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020 Oct;117(42):709-16. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0709

[60] Lyons-Ruth K, Todd Manly J, Von Klitzing K, Tamminen T, Emde R, Fitzgerald H, Paul C, Keren M, Berg A, Foley M, Watanabe H. THE WORLDWIDE BURDEN OF INFANT MENTAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDER: REPORT OF THE TASK FORCE OF THE WORLD ASSOCIATION FOR INFANT MENTAL HEALTH. Infant Ment Health J. 2017 Nov;38(6):695-705. DOI: 10.1002/imhj.21674

[61] Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, Boyce T, McNeish D, Grady M, Geddes I. Fair Society Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review). Institute of Health Equity; 2010. Available from: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf

[62] Mattern E, Lohmann S, Ayerle GM. Experiences and wishes of women regarding systemic aspects of midwifery care in Germany: a qualitative study with focus groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Nov;17(1):389. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-017-1552-9

[63] McCauley K, Elsom S, Muir-Cochrane E, Lyneham J. Midwives and assessment of perinatal mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011 Nov;18(9):786-95. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01727.x

[64] McConville F, Af Ugglas A, Tehongue B. Qualität und Würde - Hebammen im Fokus der WHO. Dtsch Hebammenzeitschrift. 2017;6:52-5.

[65] McLeish J, Redshaw M. Maternity experiences of mothers with multiple disadvantages in England: A qualitative study. Women Birth. 2019 Apr;32(2):178-84. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.05.009

[66] Oni HT, Buultjens M, Blandthorn J, Davis D, Abdel-Latif M, Islam MM. Barriers and facilitators in antenatal settings to screening and referral of pregnant women who use alcohol or other drugs: A qualitative study of midwives' experience. Midwifery. 2020 Feb;81:102595. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.102595

[67] Origlia Ikhilor P, Hasenberg G, Kurth E, Asefaw F, Pehlke-Milde J, Cignacco E. Communication barriers in maternity care of allophone migrants: Experiences of women, healthcare professionals, and intercultural interpreters. J Adv Nurs. 2019 Oct;75(10):2200-10. DOI: 10.1111/jan.14093

[68] Pangas J, Ogunsiji O, Elmir R, Raman S, Liamputtong P, Burns E, Dahlen HG, Schmied V. Refugee women's experiences negotiating motherhood and maternity care in a new country: A meta-ethnographic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019 Feb;90:31-45. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.10.005

[69] Pehlke-Milde J. Ein Kompetenzprofil für die Hebammenausbildung: Grundlage einer lernergebnisorientierten Curriculumentwicklung [dissertation]. Berlin: Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin; 2009. DOI: 10.17169/refubium-6373

[70] Pillas D, Marmot M, Naicker K, Goldblatt P, Morrison J, Pikhart H. Social inequalities in early childhood health and development: a European-wide systematic review. Pediatr Res. 2014 Nov;76(5):418-24. DOI: 10.1038/pr.2014.122

[71] Przyborski A, Wohlrab-Sahr M. Sampling. In: Qualitative Sozialforschung. 4th edition. München: Oldenbourg; 2013. p. 177-88. (Lehr- und Handbücher der Soziologie). DOI: 10.1524/9783486719550.177

[72] Ramraj C, Pulver A, O'Campo P, Urquia ML, Hildebrand V, Siddiqi A. A Scoping Review of Socioeconomic Inequalities in Distributions of Birth Outcomes: Through a Conceptual and Methodological Lens. Matern Child Health J. 2020 Feb;24(2):144-52. DOI: 10.1007/s10995-019-02838-w

[73] Renfrew MJ, Malata AM. Scaling up care by midwives must now be a global priority. Lancet Glob Health. 2021 Jan;9(1):e2-e3. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30478-2

[74] Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, Silva DR, Downe S, Kennedy HP, Malata A, McCormick F, Wick L, Declercq E. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014 Sep;384(9948):1129-45. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3

[75] Renner I. Zugangswege zu hoch belasteten Familien über ausgewählte Akteure des Gesundheitssystems. Ergebnisse einer explorativen Befragung von Modellprojekten Früher Hilfen [Access to high-risk families through selected actors of the health care system. Results of an explorative questioning of early childhood intervention pilot projects]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010 Oct;53(10):1048-55. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-010-1130-z

[76] Rosenhagen G, Boogaart H, Stimmer F. Lexikon der Sozialpädagogik und der Sozialarbeit. 4th ed. Munich: Oldenbourg; 2000.

[77] Salinas-Miranda AA, King LM, Salihu HM, Berry E, Austin D, Nash S, Scarborough K, Best E, Cox L, King G, Hepburn C, Burpee C, Richardson E, Ducket M, Briscoe R, Baldwin J. Exploring the Life Course Perspective in Maternal and Child Health through Community-Based Participatory Focus Groups: Social Risks Assessment. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2017;10(1):43-166.

[78] Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Apr;4(4):CD004667. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5

[79] Sander M, Albrecht M, Loos S, Stengel V. Studie zur Hebammenversorgung im Freistaat Bayern. Kurzfassung. Berlin: IGES; 2018. Available from: https://www.stmgp.bayern.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/hebammenstudie_kurzfassung.pdf

[80] Schaefer I, Kümpers S, Cook T. „Selten Gehörte“ für partizipative Gesundheitsforschung gewinnen: Herausforderungen und Strategien [Involving the seldom heard in participatory health research: challenges and strategies]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2021 Feb;64(2):163-70. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-020-03269-7

[81] Schlueter-Cruse M. Die Kooperation freiberuflicher Hebammen im Kontext Frueher Hilfen [dissertation]. Witten/Herdecke: Universität Witten/Herdecke; 2018.

[82] Schlueter-Cruse M, zu Sayn-Wittgenstein F. Die Vertrauensbeziehung zwischen freiberuflichen Hebammen und Klientinnen im Kontext der interprofessionellen Kooperation in den Frühen Hilfen: eine qualitative Studie. GMS Z Hebammenwiss. 2017;4:Doc03. DOI: 10.3205/zhwi000009

[83] Schmitt M, Blue A, Aschenbrener CA, Viggiano TR. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: reforming health care by transforming health professionals' education. Acad Med. 2011 Nov;86(11):1351. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182308e39

[84] Schreier M. Fallauswahl in der qualitativpsychologischen Forschung. In: Mey G, Mruck K, editors. Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien; 2017. p. 1-21.

[85] Schreier M. Sampling and Generalization. In: Flick U, editor. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection. London: SAGE Publications; 2018. p. 84-97. DOI: 10.4135/9781526416070.n6

[86] Schreier M. Varianten qualitativer Inhaltsanalyse: ein Wegweiser im Dickicht der Begrifflichkeiten. Forum Qual Sozialforschung Forum Qual Soc Res. 2014;15(1):18.

[87] Schwind B, Zemp E, Jafflin K, Späth A, Barth M, Maigetter K, Merten S, Kurth E. "But at home, with the midwife, you are a person": experiences and impact of a new early postpartum home-based midwifery care model in the view of women in vulnerable family situations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023 Apr;23(1):375. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-023-09352-4

[88] Siegmund-Schultze E, Kielblock B, Bansen T. Schwangerschaft und Geburt: Was kann die Krankenkasse tun? Gesundheitsoekonomie Qual. 2008;13(4):210-15. DOI: 10.1055/s-2008-1027223

[89] Simon S. Die ambulante Wochenbettbetreuung. Eine qualitative Studie zum Professionellen Handeln von Hebammen [dissertation]. Witten/Herdecke: Universität Witten/Herdecke; 2017.

[90] Sterzing D. Präventive Programme für sozial benachteiligte Familien mit Kindern von 0-6 Jahren. Überblick über die Angebote in Deutschland. München: Deutsches Jugendinstitut; 2012.

[91] Strübing J. Qualitative Sozialforschung: eine komprimierte Einführung für Studierende. München: Oldenbourg; 2013.

[92] Sutherland G, Yelland J, Brown S. Social inequalities in the organization of pregnancy care in a universally funded public health care system. Matern Child Health J. 2012 Feb;16(2):288-96. DOI: 10.1007/s10995-011-0752-6

[93] van Staa J, Renner I. »Man will das einfach selber schaffen« - Symbolische Barrieren der Inanspruchnahme Früher Hilfen. Ausgewählte Ergebnisse aus der Erreichbarkeitsstudie des NZFH. Köln: BZGA - Federal Centre for Health Education; 2020.

[94] VERBI Software. Consult. Sozialforschung GmbH. MAXQDA, Software für qualitative Datenanalyse. 2022.

[95] von Koeppen M, Schmidt K, Tiefenthaler S. Mit vulnerablen Gruppen forschen - ein Forschungsprozessmodell als Reflexionshilfe für partizipative Projekte. In: Wright MT, Wihofszky P, Hartung S, editors. Partizipative Forschung: Ein Forschungsansatz für Gesundheit und seine Methoden. Wiesbaden: Springer Nature; 2020. p. 21-62. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-658-30361-7_2

[96] Winkler C, Babac E. Birth Justice. Die Bedeutung von Intersektionalität für die Begleitung von Schwangerschaft, Geburt und früher Elternschaft. Oesterr Z Soziol. 2022;47:3158. DOI: 10.1007/s11614-022-00472-5

[97] Witzel A. Das problemzentrierte Interview. In: Juettemann G, editor. Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie: Grundfragen, Verfahrensweisen, Anwendungsfelder. Weinheim: Beltz; 1985. p. 227-55.

[98] Witzel A. The Problem-centered Interview. Forum Qual Sozialforschung Forum Qual Soc Res. 2000;1(1). DOI: 10.17169/fqs-1.1.1132

[99] Zoege von Manteuffel M. Hebammenausbildung: eine Untersuchung zur Qualifizierung von Hebammen vor dem Hintergrund der soziologischen Professionalisierungsdebatte [dissertation]. Hannover: Universität Hannover; 2002.