Varus deformity of the left lower extremity causing degenerative lesion of the posterior horn of the left medial meniscus in a patient with Paget’s disease of bone

Ali Al Kaissi 1,2Rudolf Ganger 2

Gabriel Mindler 2

Klaus Klaushofer 1

Franz Grill 2

1 Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Osteology at the Hanusch Hospital of WGKK and AUVA Trauma Centre Meidling, First Medical Department, Hanusch Hospital, Vienna, Austria

2 Orthopaedic Hospital of Speising, Paediatric Department, Vienna, Austria

Abstract

We report on a 42-year-old woman who presented with persistent pain in her left knee with no history of trauma. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI of the left knee showed discontinuity between the anterior and posterior horns of the left medial meniscus, causing effectively the development of degenerative lesion of the posterior horn. The latter was correlated to varus deformity of the left lower extremity associated with subsequent narrowing of the medial knee joint. The unusual craniofacial contour of the patient, the skeletal survey and the elevated serum alkaline phosphatase were compatible with the diagnosis of Paget’s disease of the bone. To alleviate the adverse effect of the mal-alignment of the left femur onto the left knee, corrective osteotomy of the left femoral diaphysis by means of fixators was performed. To the best of our knowledge this is the first clinical report describing the management and the pathological correlation of a unilateral varus deformity of the femoral shaft and degenerative lesions of the left knee in a patient with Paget’s disease of the bone.

Keywords

Paget's disease of bone, varus deformity, degenerative lesion of medial meniscus, radiology

Introduction

Paget’s disease of the bone (osteitis deformans) was first diagnosed by Sir James Paget as a disease of the osteoclast [1]. The disease is characterized by excessive osteoclastic bone resorption followed by excessive bone formation, which can lead to bone pain, bone deformity and skeletal fragility. About 20% of patients fall into the category of familial Paget’s disease in which there appears to be autosomal dominant transmission with incomplete penetrance [2]. Mutation in the sequestosome 1 gene has been encountered in one third of patients with Paget’s disease. The protein produced by this gene is important in the interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor and rank ligand signaling pathways which help regulate osteoclast function. A second gene mutation has been found in the valosine containing protein of a very rare type of familial Paget’s disease in which muscle dysfunction and dementia are prominent features [3]. The most serious complication of Paget’s disease is osteosarcoma, though it occurs in less than 1% of patients with Paget’s disease, it is considered at a significantly higher rate than in non-affected individuals. Delayed diagnosis might be the most likely etiology behind the fatality of osteosarcoma in patients with Paget’s disease [3], [4].

Linear growth of long bones takes place at the physis and epiphysis with the addition of new bone. Growth displaces angulation away from the end of the bone, instead of decreasing the angle. The remodeling of angular deformity is primarily a response to functional stresses on the femur by muscle pull and the force of the gravity. Angular deformities of the femoral shaft occur more frequently in fractures of the proximal third of the femoral shaft, often with medial angulation, and correct themselves more slowly in the proximal third than in the distal two thirds [5]. Femoral varus deformity is also not uncommon in patients with hypophosphataemic rickets [6]. Patients with Paget’s disease of the bone (PDB) run a significantly increased risk of developing osteoarthritis [7].

The C-shaped medial meniscus covers 50% of the medial tibial plateau and has ligamentous attachments to the tibia through the coronary ligament and to the deep medial collateral ligament through the meniscotibial ligament. These attachments prevent the medial meniscus from translating more than 2–5 mm with knee motion. The medial and lateral meniscus share the load and reduce the contact stresses across the knee joint, transmitting 50–70% of the load in extension and 85–90% of the load in flexion [8].

Clinical report

A 42-year-old woman was referred to our department because of pain in her left knee. The pain was of constant nature and had risen gradually causing effectively antalgic gait. Pain got worse with movement and there was no history of trauma reported. Clinical examination showed unusual craniofacial contour of a large skull with frontal bossing. Decreased active and passive range of motion (ROM) associated with relative left thigh atrophy most likely because of feedback inhibition to the quadriceps due to pain. Palpation of the left knee showed joint line tenderness, and extensor mechanism pathology associated with mechanical blocking (i.e. decrease in active and passive motion). Squatting (hyperflexion) exacerbated the pain.

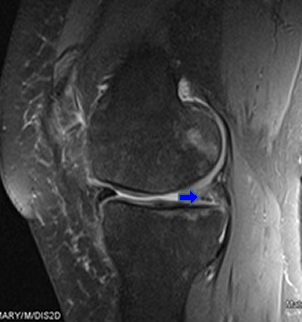

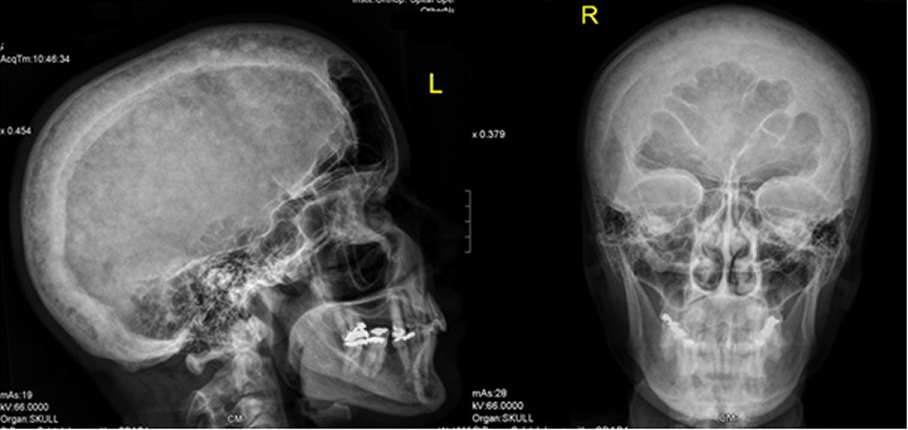

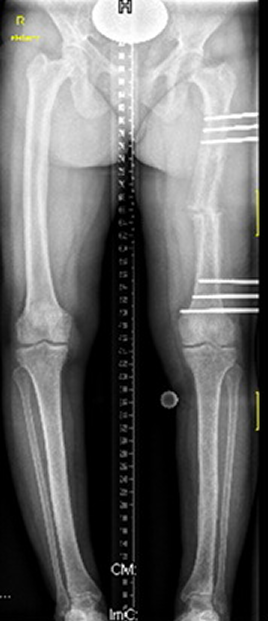

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI of the left knee showed no attachment of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus to the tibial plateau, but instead the meniscofemoral ligament (ligament of Wrisberg) joined the posterior horn of the meniscus to the lateral surface of the medial femoral condyle, i.e. discontinuity between the anterior and posterior horns, causing effectively the development of degenerative lesion of the posterior horn of the left medial meniscus (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). On the bases of skeletal survey, weight bearing anteroposterior left lower limb radiograph showed varus deformity of the left lower extremity and narrowing of the medial knee joint and narrowing of the hip joint as well associated with unusual cortical thickening and bone enlargement. The angles of the frontal plane alignment were measured according to Paley: mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA) = 106°, medial proximal tibial angle (mMPTA) = 85°, and the distal tibial angle (mLDTA) = 93°. These measurements were compared to weight bearing full length radiographs, which are considered to be the standard of reference for planning corrective surgery. The lateral distal left femoral angle measured 106°, which means approximately 20° deviation from the norms (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]). Skull radiographs showed the cotton wool appearance, disorganized trabecular with areas of sclerosis which are poorly defined and fluffy. Widening of the diploic space and relatively indistinct outer table, and the frontal sinuses are enlarged. No hyperostosis of the skull base was noted. These findings reflect the underlying pathologic changes of osteoblastic repair and are usually pathognomonic (Figure 3 [Fig. 3]). The patient underwent laboratory investigations with blood and urinary tests. Serum bone alkaline phosphatase was high (four times greater than the normal value), which is reflective of the rapid new bone turnover. Other laboratory studies showed normal levels of calcium, phosphate, PTH and vitamin D levels.

Figure 1: Sagittal T1-weighted MRI of the left knee shows no attachment of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus to the tibial plateau, but instead the meniscofemoral ligament (ligament of Wrisberg) joins the posterior horn of the meniscus to the lateral surface of the medial femoral condyle, i.e. discontinuity between the anterior and posterior horns, causing effectively the development of degenerative lesion of the posterior horn of the left medial meniscus (arrow).

Figure 2: Weight bearing anteroposterior left lower limb radiograph shows varus deformity of the left lower extremity and narrowing of the medial knee joint and narrowing of the hip joint as well associated with unusual cortical thickening and bone enlargement (arrows). The lateral distal left femoral angle measured 106 °, which means approximately 20° deviation from the norms (arrow).

Figure 3: Skull radiographs showed the cotton wool appearance, disorganized trabecular with areas of sclerosis which are poorly defined and fluffy. Widening of the diploic space and relatively indistinct outer table, the frontal sinuses are enlarged. No hyperostosis of the skull base was noted. These findings reflect the underlying pathologic changes of osteoblastic repair and are usually pathognomonic.

Treatment

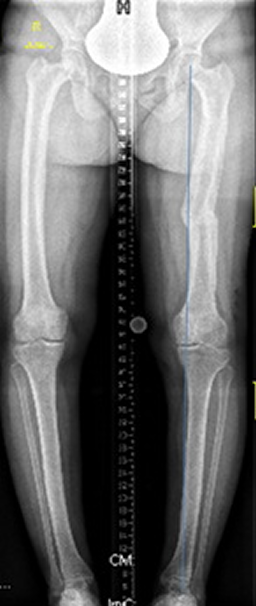

The patien underwent diagnostic arthroscopy of the left knee and mid-shaft osteotomy of the left femur with acute correction against varus position by means of fixationas which was done by using a unilateral fixator (LRS, Biomet Company USA) (Figure 4 [Fig. 4]). Six months postoperative radiograph showed that complete healing was accomplished, and the fixator was removed. There was a dramatical improvement of the mechanical axis, though still minimal varus deviation exists (Figure 5 [Fig. 5]).

Figure 4: The patient underwent diagnostic arthroscopy of the left knee and mid-shaft osteotomy of the left femur with acute correction against varus position by means of fixations which was done by using a unilateral fixator (LRS, Biomet Company USA).

Figure 5: Six months postoperative radiograph showed that complete healing was accomplished, and the fixator was removed. There was a dramatical improvement of the mechanical axis, though still minimal varus deviation exists.

Discussion

Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) is a focal disorder of bone metabolism, characterized by an intial phase of bone resorption that begins in subchodral bone and moves through the affected bone. The bone thickens with the deposition of woven bone admixed with lamellar bone, and the marrow is replaced by peritrabecular fibrosis associated with capillary ingrwoth [9]. The complications of Paget’s disease stem from this bony overgrowth, and include deformity, bone pain, fracture, nerve compression syndromes and orthopedic complications.

The etiology of Paget’s disease continues to be a subject of debate. There is evidence to suggest that PDB might be caused by a slow-virus infection of osteoclasts. Khan et al. [10] investigated the hypothesis that dog ownership may increase the risk of Paget’s disease of bone by means of a case control study, led investigators to seek a viral etiology to the disease. Evidence accrued for infection of the osteoclast by measels virus or canine distemper virus in patients with Paget’s disease of bone, with variable seeding of the osteoclasts in bone accounting for the distribution of the pagetic lesions in a given individual. This theory faltered as genetic probing of bone cells for evidence of transcripts of these viruses led to conflicting results [3], [11]. Genetic factors play an important role in PDB and mutations or polymorphisms and these have been identified in four genes that cause classical Paget’s disease and related syndromes. These include TNFRSF11A, which encodes RANK, TNFRSF11B which encodes osteoprotegerin, VCP which encodes p97, and SQSTM1 which encodes p62. All of these genes play a role in the RANK-NFkappaB signalling pathway and it is likely that the mutations predispose to PDB by disrupting normal signalling, leading to osteoclast activation [3], [12].

Antiresorptive treatment suppresses bone turnover in Paget’s disease and improves the appearance of pagetic lesions on isotope bone scan, but the clinical evidence base only supports the use of antiresorptive drugs for the treatment of bone pain. Bone pain in Paget’s disease can be managed either with simple analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or with antiresorptive drugs such as calcitonin and bisphosphonates. Interestingly, Chung and Keen [13] reported that with a single infusion of Zoledronate, they were able to achieve clinical and biochemical remission in their patient with active Paget’s disease who had become resistant to pamidronate [14]. Buckler et al. [15] reported a dose-ranging study of single doses of Zoledronic acid. One hundred seventy-six patients were enrolled, with baseline serum alkaline phosphatase at least twice the upper limits of normal. A therapeutic response was defined as 50% reduction in serum alkaline phosphatase from baseline or normalization following treatment. With 400 µg, a 50% decrease from baseline serum alkaline phosphatase was seen in 46% patients, and normalization in 20% (this dose was far superior to 50 µg, 100 µg, 200 µg, and placebo). Side effects such as fever, skeletal pain, and asymptomatic hypocalcemia were dose-related and transient. Green et al. [16] investigated the pharmacologic effects of a new bisphosphonate compound, CGP 42'446 [2-(imidazol-1-yl)-1-hydroxyethylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate], on bone metabolism. They concluded that CGP 42'446 is a promising new, highly potent bisphosphonate for the suppression of the increased bone resorption associated with various diseases.

The medial meniscus is semicircular covering about 64% of the area of the medial tibila plateau. It is broader posteriorly than anteriorly. The anterior and the posterior horns attach anterior to the ACL and PCL tibial insertion sites within the intercondylar fossa, respectively. Peripherally, the medial meniscus is firmly attached to the joint capsule and to the deep MCL. Two patterns of meniscal injury are seen; traumatic and or degenerative. Degenerative tears are typically complex and not amenable to repair. Traumatic tears are often associated with ACL injuries and are usually amenable to repair. The incidence of meniscal tears rises significantly with the chronicity of the ACL tear, ranging from 65% in acute injuries to 90% in chronic injuries. The lateral meniscus is more frequently torn in the acute ACL injury due to rotary forces. The medial meniscus is more frequently torn in chronic ACL-deficiency due to repeated episodes of instability and its relative lack of mobility [17], [18].

In summary

Paget’s disease is a progressive metabolic bone disorder which impairs bone metabolism by increasing bone resorption and formation. Pain, fractures, and deformity of the long bones are among the most common clinical presentations. In our patient, the degenerative lesion of the posterior horn of the left medial meniscus was the prime clinical presentation. The varus deformity of the left femur caused mal-alignment of the axis with subsequent impaired distribution of force over the load-bearing left medial meniscus. In other words, in this patient, the varus knee correlated to more forces transmitted to the medial compartment leads to the development of osteoarthritis. Finally, we stress on the necessity of phenotypic characterization as a baseline tool for the establishment of proper management.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Paget J. On a form of chronic inflammation of bones (osteitis deformans). Med Chir Trans. 1877;60:37-64.[2] Kanis JA, editor. Pathophysiology and treatment of Paget's disease of bone. 1st ed. London: Martin Dunitz; 1992.

[3] Ralston SH, Langston AL, Reid IR. Pathogenesis and management of Paget's disease of bone. Lancet. 2008 Jul 12;372(9633):155-63. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61035-1

[4] Selby PL, Davie MW, Ralston SH, Stone MD; Bone and Tooth Society of Great Britain; National Association for the Relief of Paget's Disease. Guidelines on the management of Paget's disease of bone. Bone. 2002 Sep;31(3):366-73. DOI: 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00817-7

[5] Friedman RJ, Wyman ET Jr. Ipsilateral hip and femoral shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986 Jul;(208):188-94.

[6] Al Kaissi A, Farr S, Ganger R, Klaushofer K, Grill F. Windswept lower limb deformities in patients with hypophosphataemic rickets. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013 Dec 6;143:w13904. DOI: 10.4414/smw.2013.13904

[7] Helliwell PS. Osteoarthritis and Paget's disease. Br J Rheumatol. 1995 Nov;34(11):1061-3. DOI: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.11.1061

[8] Greis PE, Bardana DD, Holmstrom MC, Burks RT. Meniscal injury: I. Basic science and evaluation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002 May-Jun;10(3):168-76.

[9] Siris E, Roodman GD. Paget's disease of bone. In: Favus MJ, editor. Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. Washington (DC): American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; 2003. p. 495-506.

[10] Khan SA, Brennan P, Newman J, Gray RE, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA. Paget's disease of bone and unvaccinated dogs. Bone. 1996 Jul;19(1):47-50. DOI: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00117-2

[11] Rima BK, Gassen U, Helfrich MH, Ralston SH. The pro and con of measles virus in Paget's disease: con. J Bone Miner Res. 2002 Dec;17(12):2290-2. DOI: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2290

[12] Janssens K, Van Hul W. Molecular genetics of too much bone. Hum Mol Genet. 2002 Oct 1;11(20):2385-93. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/11.20.2385

[13] Chung G, Keen RW. Zoledronate treatment in active Paget's disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 Mar;62(3):275-6. DOI: 10.1136/ard.62.3.275

[14] Arden-Cordone M, Siris ES, Lyles KW, Knieriem A, Newton RA, Schaffer V, Zelenakas K. Antiresorptive effect of a single infusion of microgram quantities of zoledronate in Paget's disease of bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 1997 May;60(5):415-8. DOI: 10.1007/s002239900255

[15] Buckler H, Fraser W, Hosking D, Ryan W, Maricic MJ, Singer F, Davie M, Fogelman I, Birbara CA, Moses AM, Lyles K, Selby P, Richardson P, Seaman J, Zelenakas K, Siris E. Single infusion of zoledronate in Paget's disease of bone: a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Bone. 1999 May;24(5 Suppl):81S-85S. DOI: 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00071-X

[16] Green JR, Müller K, Jaeggi KA. Preclinical pharmacology of CGP 42'446, a new, potent, heterocyclic bisphosphonate compound. J Bone Miner Res. 1994 May;9(5):745-51. DOI: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090521

[17] Kocher MS, Klingele K, Rassman SO. Meniscal disorders: normal, discoid, and cysts. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003 Jul;34(3):329-40. DOI: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00008-7

[18] Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007 Oct;35(10):1756-69. DOI: 10.1177/0363546507307396