Peer reviewing critical care: a pragmatic approach to quality management

Jan-Peter Braun 1Hanswerner Bause 2

Frank Bloos 3

Götz Geldner 4

Marc Kastrup 1

Ralf Kuhlen 5

Andreas Markewitz 6

Jörg Martin 7

Hendrik Mende 8

Michael Quintel 9

Klaus Steinmeier-Bauer 1

Christian Waydhas 10

Claudia Spies 1

NeQuI (quality network in intensive care medicine)

1 Dept. of Anaesthesiology and Surgical Intensive Care Medicine, Charité – University Medicine Berlin, Germany

2 Dept. of Anaesthesiology and Surgical Intensive Care Medicine, Asklepios Hospital Altona, Hamburg, Germany

3 Dept. of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, University Hospital Jena, Germany

4 Dept. of Anaesthesiology, Intensive Care Medicine, Pain Therapy and Emergency Medicine, Ludwigsburg, Germany

5 Helios Hospital Berlin-Buch, Berlin, Germany

6 Dept. of Cardiac and Vascular Surgery, Military Central Homebase Hospital Koblenz, Germany

7 Medical Director, Hospital Göppingen, Germany

8 Regional Hospitals Holding, RKH GmbH, Ludwigsburg, Germany

9 Dept. Anaesthesiology, Emergency and Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospital Göttingen, Germany

10 Dept. of Trauma and Reconstructive Surgery, University Hospital Essen, Germany

Abstract

Critical care medicine frequently involves decisions and measures that may result in significant consequences for patients. In particular, mistakes may directly or indirectly derive from daily routine processes. In addition, consequences may result from the broader pharmaceutical and technological treatment options, which frequently involve multidimensional aspects. The increasing complexity of pharmaceutical and technological properties must be monitored and taken into account. Besides the presence of various disciplines involved, the provision of 24-hour care requires multiple handovers of significant information each day. Immediate expert action that is well coordinated is just as important as a professional handling of medicine's limitations.

Intensivists are increasingly facing professional quality management within the ICU (Intensive Care Unit). This article depicts a practical and effective approach to this complex topic and describes external evaluation of critical care according to peer reviewing processes, which have been successfully implemented in Germany and are likely to gain in significance.

Keywords

peer review, quality management, intensive care medicine, evidence based medicine, effectiveness

Introduction

Critical care medicine frequently involves decisions and measures that may result in significant consequences for patients. In particular, mistakes may directly or indirectly derive from daily routine processes. In addition, consequences may result from the broader pharmaceutical and technological treatment options, which frequently involve multidimensional aspects. The increasing complexity of pharmaceutical and technological properties must be monitored and taken into account. Besides the presence of various disciplines involved, the provision of 24-hour care requires multiple handovers of significant information each day. Immediate expert action that is well coordinated is just as important as a professional handling of medicine's limitations.

Intensivists are increasingly facing professional quality management within the ICU (Intensive Care Unit). This is highlighted by the Vienna declaration on ICU patient safety that was signed at the 2009 European convention of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) [1]. It includes the commitment to actively pursue quality management within the setting of intensive care medicine. This article depicts a practical and effective approach to this complex topic and describes external evaluation of critical care according to peer reviewing processes, which have been successfully implemented in Germany and are likely to gain in significance.

Learning process in critical care: learn from mistakes, think within processes

ICU quality management refers to multiple professions and disciplines that cooperate in critical care medicine, with the parties involved being highly responsible for its successful implementation. Competences of the various professions and disciplines must be well coordinated and concentrated. Frequently, concepts of evidence-based medicine are insufficiently applied [2]. Concepts of evidence-based medicine may only be successfully realised once integrated into goal-oriented, constantly updated local standard operating procedures (SOP). It is the responsibility of quality management to ensure a reasonable balance between high expectations and reality. Sustainable quality management has been described by Donabedian and can be applied to intensive care medicine as well [3]:

- Structure quality: What structural and organizational preconditions must be met? Is the available staff qualified and is the present technology adequate?

- Process quality: Are core processes and standards of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures defined? Are they based on evidence?

- Outcome quality: Are (therapy-) goals defined and is outcome-relevant data comprehensible? Are transparent outcomes available?

In 1997, the minimum requirements of an ICU have been defined and published by Ferdinande [4] on behalf of the ESICM, which are currently being revised. So far, only structural guidelines were defined for ICUs. Development and realisation of a structural standard (construction guidelines, technology, organizational aspects) of critical care is quite challenging, as current and prospective demands of modern critical care must be taken into account, e.g. the construction of an ICU must consider potential requirements that may result from increasing colonisation and infection with multiresistant strains [5]. Yet, structures are only the beginning when considering the quality of critical care.

Daily routine refers to processes that must be defined and described, in order to be regularly applied. Studies on patient safety and learning from errors (Sentinel-Events-Evaluation-(SEE) studies [6], [7]) have shown that particularly routine processes put ICU patients at risk, e.g. process chains of pharmaceutical preparation and application. The considerable amount of the literature on lung protective ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [8], [9], [10] or weaning strategies [11], [12], [13], [14] documents that there is a viable discussion in regard to core processes of critical care medicine. Due to the availability of a number of publications dealing with core processes of critical care (ventilation, sedation, circulatory support), expert committees developed national and international guidelines. Evidence levels of these guidelines increase as they are being continuously updated and refined. Examples are the guidelines for sedation, circulatory support after cardiac surgery, sepsis, or diagnosis and treatment of heart failure [15], [16], [17], [18]. However, guidelines do not warrant knowledge transfer into practice (implementation failure). Patients can only benefit from the progress of medicine once guidelines are being integrated into local standards and action is trained according to goal-oriented processes.

Implementation of evidence-based medicine on a daily basis remains the central issue in regard to the quality of medicine. It may initially appear as complex, particularly due to the challenges of the description of resources and processes and the requirement for a common definition of evidence-based standards within interdisciplinary teams.

The fact that the German Society for Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und lntensivmedizin, DGAI) und the German Interdisciplinary Association of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine (Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin, DIVI) agreed on a common core data set of intensive care medicine in 2004 can be seen as an important progress in this issue [19]. This core data set did not only facilitate description and comparison beyond medical disciplines, it was the precondition for quality management on a larger scale allowing analysis of an immense amount of core data [20]. Yet, analysis of this core data set may be associated with elaborate data detection and analysis, since structures like automated data collection such as patient data management systems (PDMS) are not the nationwide standard. On the other hand, this core data set is the basis for performance-related critical care compensation within the German system of case-based lump sums [21]. Complex flat rates of ICU treatment are obtained from data of illness severity and treatment effort, which are both reflected by specific scores recorded during the entire ICU stay [22]. In order to calculate complex flat rates, the item “Glasgow Coma Scale” is removed from the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) [23], with 10 items of the Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System (TISS 28) [24] being added. Once reaching certain limits, the resulting sum scores lead to markedly improved compensation.

It can be of further advantage to record illness severity and treatment effort in combination, since studies from Scandinavia show that – compared to illness severity – treatment effort may decrease over time without a resulting decrease of treatment quality as reflected by risk-adjusted mortality [25]. This showed that treatment effort and cost do not directly correlate with qualitative outcomes of ICU treatment, meaning that more effort is not necessarily better. Preliminary data of the Charité indicates similar results during an observation period of 5 years.

When evaluating process effectiveness and efficiency in patients, patient benefit is most important. Discussions on the benefits from pulmonary artery catheters versus other advanced hemodynamic monitoring, enteral versus parenteral nutrition, or the general abandonment of tonometry are just a few examples for the critical questioning of benefits resulting from ICU processes. As evidence may change over time, standards must be updated and refined in regular intervals and are only valid for a limited period of time!

Focusing on the essentials: staff, processes, patients

Processes of intensive care medicine generally affect the staff as processes are usually executed from humans. Efficient and effective processes relate to efficient and effective staff. Process optimisation is a matter of employee organisation as about 2/3 of the expenditures spent in critical care refers to human resources. Billing of complex treatments of critical care within the German Diagnosis Related Groups (GDRG)-System structurally depends on the availability of qualified physicians and caregivers, which present one of the most important structural criteria within an ICU. 24-hour presence of critical care-experienced doctors and caregivers is expected [26]. The importance of 24-hour presence and hospital availability of a qualified and experienced critical care team as a fast back-up for urgent situations and acute complications has been investigated in detail by a major Australian study (ICU Liaison Nurse) [27]. ICU staffs practicing outcome-relevant procedures in critically ill patients have been identified as a statistically significant factor in regard to patient outcome improvement. A study conducted at the John’s Hopkins University showed that failure in providing punctual ICU treatment is associated with worse outcomes [2].

Which core processes should be highlighted due to evidence-based findings and which bedside processes influence patient outcomes? In order to answer these questions, it is necessary to systematically evaluate key indicators of outcome, that are detectable, reflect clinical settings, show validity and relate to patient outcomes. Systematic approaches in order to develop indicators that refer to critical care quality have been described extensively by Pronovost and colleagues, including associated difficulties [28]. Following the analysis and extensive discussion by an expert committee of the DGAI, key indicators of critical care were elaborated: Spanish indicators previously published were translated [29] and subsequently reduced to independent indicators by consensus. All of these key indicators significantly influenced ICU patient outcome in previous publications. Any indicator could be characterised based on quality of structure, process and outcome. On various ICUs of the Charité University Hospital, Kastrup et al. [30] identified indicators that displayed self-defined quality-reflecting targets of ICU core processes and showed that achievement of targeted goals led to shorter ICU length of stay, which is likely to be associated with outcome improvement. These so-called key performance indicators (KPI) are captured on a regular basis and allow for conclusions in regard to adherence to treatment standards and implementation of core processes.

Rothen and colleagues [31] observed a correlation between standardised ICU patient outcome (SMR = standardized mortality ratio) and standardised resource consumption. They observed that mortality was lower on ICUs with higher caregiver-to-ICU-patient ratios. Contrary, an analogue correlation could not be observed in regard to physicians! Of course, this result may be critically discussed due to methodological issues. Yet, caregivers work the closest with patients and accomplish the majority of ICU patient processes. Apart from a discussion regarding task delegation or demarcation of the various professions, analyses of patient processes present a central issue regarding ICU treatment quality. Process definition and management besides analysis of necessity and feasibility characterise the challenges of such patient process analyses.

Process management that targets the reduction and prevention of insecurities and conflict situations is an absolute necessity in order to investigate the increased risk of burnout within an ICU staff. Approximately 1/3 of ICU caregivers suffer from burnout syndromes according to a French study [32]. The influence of teamwork and team processes on patient outcome was shown in a recent publication [33]: input criteria were defined as team composition, team management, task structures, specific requirements and perspectives; task processes included communication, management, task delegation, coordination, as well as decision process; outcome criteria were defined as patient outcome (adverse events, mortality, length of stay, health related quality of life, end-of-life processes) as well as team outcome, which was assessed by satisfaction with team and job, team morale, stress, burnout, staff exchange, structurally describing links between different qualities and levels of quality.

Various aspects of quality must be considered and balanced in order to have enduring success within a system or a company. “Balanced score cards” ranking interaction of indicators within different levels of quality have been used within the economy and can be applied to health care systems as well [34].

- Customer level: To what extent are we stake-holder oriented? (stakeholders of critical care refer to patients, staff, other disciplines or areas connected to the ICU)

- Education level: In what way are goals or willingness to learn and advance present? Is knowledge passed on? Is there a learning system?

- Process level: How well are processes defined and which have to be elaborated? Where are the weaknesses? Are standards being realised?

- Financial level: Are we efficient and effective? Are resources and added value reasonably balanced? Do we consider the overall success?

Success is only likely to occur once these levels are applied in combination since none of them is viable alone.

Realising quality management within critical care

The primary intent of quality management is to target problematic fields within an institution and to get these under lasting control. Vagts et al. [35] may be right when questioning the intended purpose and reality of certifying intensive care medicine. In regard to the limitation of resources within medicine, it is always important to consider the balance between concrete expenditures and definite benefits. The need for more efficient tools of quality management within critical care is obvious. Which techniques can be used for this? The available literature describes a number of potential solutions, of which some provide concise solutions.

The easiest way to prevent mistakes or neglects is to work according to checklists. These have been used for decades within aviation and other disciplines and could be successfully applied to medicine by checking adherence to evidence-based standards off such lists [36]. Byrnes et al. [37] showed that adherence to 14 “best practice” goals of critical care could be increased to 99.7% after working with checklists. Once processes are standardised they can be monitored and controlled by generating report sheets for previously defined performance indicators. The initial goal should not be to achieve a maximum score but to target process optimisation reflected by improved key indicator scores. Goals should be realistic since unrealistic aims cause frustration and defence. Approaches of continuous quality improvement are described in detail within a review from Gallesio and colleagues [38]. Certainly, greater progress due to implementation of quality-improving measures is observed on ICUs with major quality shortcomings than on ICUs starting at higher levels due to previous efforts.

In addition to internal quality evaluation, the authors explicitly address external evaluation according to peer reviewing processes. Once quality-improving measures have been initiated and all ICU parties involved know both strengths and shortcomings of their ICU, external evaluation by peer review is suggested in order to achieve continuous improvement of quality.

ICU peer reviewing in Germany

In 2006, Baden-Württemberg [39] and Hamburg were the first to launch critical care medicine networks. In 2009, they were followed by Berlin/Brandenburg. Primary goal of such networks is to support the implementation of evidence-based medicine within daily routine and to improve both quality and balance between effectiveness and efficiency. One of their main tools is to peer review the critical care treatment provided to patients. Mutual visits of colleagues as well as learning from each other at eye level are the basis for such reviews. Peer reviews particularly highlight collegiality as well as interdisciplinary structures since they explicitly target improvement of communication between various professions and disciplines. In addition, participation of patients and/or their legal proxies in important decisions is structurally promoted.

In the meantime, peer reviews of critical care medicine have been standardised. Mutual responsibility, accordance with transparency, and commitment to absolute confidentiality towards third parties are characteristics of a professional external evaluation. When organising such peer reviews, written statements must be obtained prior to review visits, as reviewers must declare confidentiality and ICU-responsible management must approve. Chief physicians and caregivers of visited ICUs participate in the review process. The reviewer team consists out of two physicians specialised in critical care and one board-certified caregiver, with all reviewers employed at different hospitals. Reviewer assignment particularly takes into account that none of the participants involved is employed by a directly competing hospital. During the pilot stage, both the German Society for Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (DGAI) and the Alliance of German Anaesthesiologists support peer reviews in terms of financing, staff and through the work within scientific working groups.

Standardised peer reviews focus on the systematic evaluation of the qualities of ICU structure, process and outcome. Prior to the visit, a list of the questions asked by the reviewers is provided to the ICU staff being visited, since it is in the interest of quality management that ICUs evlaluate themselves before being evaluated by external reviewers. How this happens and to what extent is left to the ICU expecting a visit.

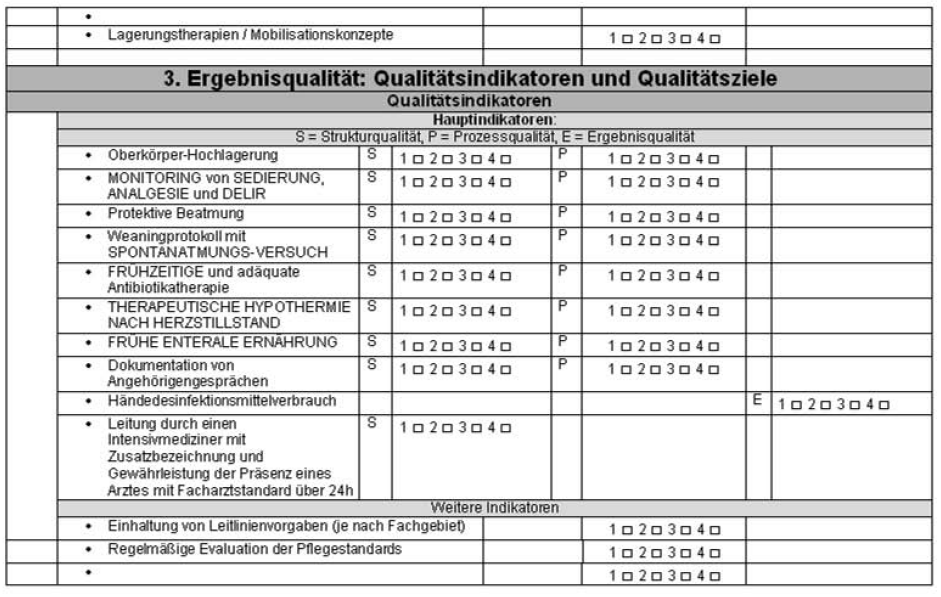

Following the official introduction of participants from both sides, questions regarding visited ICUs are asked to the ICU staff in charge. Based on questionnaires used within clinically approved certification procedures and quality indicators of intensive care medicine, a review questionnaire applying Donabedian techniques was developed. It addresses all aspects of critical care medicine in a brief – yet concise manner (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). Questions regarding the topics a) basics and organisation, b) staff, and c) patients target the quality of structures and processes. Questions in regard to quality of outcome are classified as either indicators of quality or aims of quality. The remaining part of the questionnaire refers to questions regarding the controlling and reporting systems. The amount of credits assigned depends on answer categories. Choices are “does not apply” (= 1 credit), “planned or in progress” (= 2 credits), “partially applies” (= 3 credits) und “applies” (= 4 credits). The maximum score is 420 credits resulting from approximately 100 questions. However, these scores should not be misunderstood as a grading but interpreted as landmarks in terms of prospective peer review evaluations.

Figure 1: Peer review questionnaire

Once the questionnaire completed, a joint inspection of the ICU follows in order to get to know ICU structures and perform bedside evaluation of adherence to “good practice”.

After this, reviewers and ICU staff in charge meet to share their impressions and ratings. Collegial ideas like learning from one another and self-improvement dominate the entire peer review. Within this context, it is irrelevant whether “peers” are employed in hospitals of different care levels. The aim is to evaluate an ICU based on its potential and its level of care provided. ICUs in hospitals providing maximum medical care may be as organised and structured as ICUs in hospitals providing basic medical care. The willingness to support each other in the evaluation and elaboration of potential problem solutions is explicitly expected from peer reviews.

After the closing meeting, the reviewer team meets one last time in order to write the final report, which is based on reviewer consensus. Strenghts, weaknesses, opportunities and threats are rated by a structured SWOT analysis, the questionnaire score being attached to this. This final report may serve as a landmark to the hospital staff. Potential resource shortages and special achievements are be pointed out.

Consequences resulting from review processes should be understood as a continuous improvement of quality. Besides, they offer suggestions to hospital management in terms of consulting. The final report will be handed out in person to the attending ICU physician, whereas the visited ICU department hands out their evaluation of the reviewer team.

In conclusion, the implementation of ICU peer reviews based on the common data set of the DGAI and DIVI offers the regional opportunity to realise evidence-based and locally adapted quality management, resulting in the formation of a German ICU communication platform that serves the best interest of patients, doctors and caregivers.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

The declarations of conflict of interest of all authors can be viewed on request.

References

[1] Moreno RP, Rhodes A, Donchin Y; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Patient safety in intensive care medicine: the Declaration of Vienna. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(10):1667-72. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-009-1621-2[2] Pronovost PJ, Rinke ML, Emery K, Dennison C, Blackledge C, Berenholtz SM. Interventions to reduce mortality among patients treated in intensive care units. J Crit Care. 2004;19(3):158-64. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.07.003

[3] Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691-729. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x

[4] Ferdinande P. Recommendations on minimal requirements for Intensive Care Departments. Members of the Task Force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23(2):226-32. DOI: 10.1007/s001340050321

[5] Gastmeier P, Schwab F, Geffers C, Rüden H. To isolate or not to isolate? Analysis of data from the German Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System regarding the placement of patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in private rooms in intensive care units. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(2):109-13. DOI: 10.1086/502359

[6] Valentin A, Capuzzo M, Guidet B, Moreno RP, Dolanski L, Bauer P, Metnitz PG; Research Group on Quality Improvement of European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; Sentinel Events Evaluation Study Investigators. Patient safety in intensive care: results from the multinational Sentinel Events Evaluation (SEE) study. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(10):1591-8. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-006-0290-7

[7] Valentin A, Capuzzo M, Guidet B, Moreno R, Metnitz B, Bauer P, Metnitz P; Research Group on Quality Improvement of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM); Sentinel Events Evaluation (SEE) Study Investigators. Errors in administration of parenteral drugs in intensive care units: multinational prospective study. BMJ. 2009;338:b814. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b814

[8] Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Morris A, Ancukiewicz M, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(4):327-36. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa032193

[9] Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-8. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801

[10] Villar J, Pérez-Méndez L, López J, Belda J, Blanco J, Saralegui I, Suárez-Sipmann F, López J, Lubillo S, Kacmarek RM; HELP Network. An early PEEP/FIO2 trial identifies different degrees of lung injury in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(8):795-804. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1534OC

[11] Esteban A, Alía I, Tobin MJ, Gil A, Gordo F, Vallverdú I, Blanch L, Bonet A, Vázquez A, de Pablo R, Torres A, de La Cal MA, Macías S; Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Effect of spontaneous breathing trial duration on outcome of attempts to discontinue mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(2):512-8.

[12] Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, Taichman DB, Dunn JG, Pohlman AS, Kinniry PA, Jackson JC, Canonico AE, Light RW, Shintani AK, Thompson JL, Gordon SM, Hall JB, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):126-34. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60105-1

[13] Lellouche F, Mancebo J, Jolliet P, Roeseler J, Schortgen F, Dojat M, Cabello B, Bouadma L, Rodriguez P, Maggiore S, Reynaert M, Mersmann S, Brochard L. A multicenter randomized trial of computer-driven protocolized weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(8):894-900. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1780OC

[14] Navalesi P, Frigerio P, Moretti MP, Sommariva M, Vesconi S, Baiardi P, Levati A. Rate of reintubation in mechanically ventilated neurosurgical and neurologic patients: evaluation of a systematic approach to weaning and extubation. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(11):2986-92. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818b35f2

[15] Martin J, Heymann A, Bäsell K, Baron R, Biniek R, Bürkle H, Dall P, Dictus C, Eggers V, Eichler I, Engelmann L, Garten L, Hartl W, Haase U, Huth R, Kessler P, Kleinschmidt S, Koppert W, Kretz FJ, Laubenthal H, Marggraf G, Meiser A, Neugebauer E, Neuhaus U, Putensen C, Quintel M, Reske A, Roth B, Scholz J, Schröder S, Schreiter D, Schüttler J, Schwarzmann G, Stingele R, Tonner P, Tränkle P, Treede RD, Trupkovic T, Tryba M, Wappler F, Waydhas C, Spies C. Evidence and consensus-based German guidelines for the management of analgesia, sedation and delirium in intensive care – short version. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2010;8:Doc02. DOI: 10.3205/000091

[16] Carl M, Alms A, Braun J, Dongas A, Erb J, Goetz A, Goepfert M, Gogarten W, Grosse J, Heller AR, Heringlake M, Kastrup M, Kroener A, Loer SA, Marggraf G, Markewitz A, Reuter D, Schmitt DV, Schirmer U, Wiesenack C, Zwissler B, Spies C. S3 guidelines for intensive care in cardiac surgery patients: hemodynamic monitoring and cardiocirculary system. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2010;8:Doc12. DOI: 10.3205/000101

[17] Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, Gerlach H, Calandra T, Cohen J, Gea-Banacloche J, Keh D, Marshall JC, Parker MM, Ramsay G, Zimmerman JL, Vincent JL, Levy MM; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Management Guidelines Committee. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):858-73. DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000117317.18092.E4

[18] European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); Heart Failure Association (HFA); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); European Society of Emergency Medicine (EuSEM); European Federation of Internal Medicine (EFIM); European Union Geriatric Medicine Society (EUGMS); American Geriatrics Society (AGS); European Neurological Society (ENS); European Federation of Autonomic Societies (EFAS); American Autonomic Society (AAS), Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, Dahm JB, Deharo JC, Gajek J, Gjesdal K, Krahn A, Massin M, Pepi M, Pezawas T, Granell RR, Sarasin F, Ungar A, van Dijk JG, Walma EP, Wieling W, Abe H, Benditt DG, Decker WW, Grubb BP, Kaufmann H, Morillo C, Olshansky B, Parry SW, Sheldon R, Shen WK; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), Vahanian A, Auricchio A, Bax J, Ceconi C, Dean V, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hobbs R, Kearney P, McDonagh T, McGregor K, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Vardas P, Widimsky P, Auricchio A, Acarturk E, Andreotti F, Asteggiano R, Bauersfeld U, Bellou A, Benetos A, Brandt J, Chung MK, Cortelli P, Da Costa A, Extramiana F, Ferro J, Gorenek B, Hedman A, Hirsch R, Kaliska G, Kenny RA, Kjeldsen KP, Lampert R, Mølgard H, Paju R, Puodziukynas A, Raviele A, Roman P, Scherer M, Schondorf R, Sicari R, Vanbrabant P, Wolpert C, Zamorano JL. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2631-71. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

[19] Martin J, Schleppers A, Fischer K, Junger A, Klöss Th, Schwilk B, Pützhofen G, Bauer M, Krieter H, Reinhart K, Bause H, Kuhlen R, Heinrichs W, Buchardi H, Waydhas C. Der Kerndatensatz Intensivmedizin: Mindestinhalte der Dokumentation im Bereich der Intensivmedizin. Anästh Intensivmed. 2004;45:207-16.

[20] Braun J, Schleppers A, Martin J, Waydhas C, Burchardi H, Frei U, Kox W, Spies C, Hansen D. Intensivmedizinischer Kerndatensatz: Nur zur Qualitätssicherung? Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin. 2004;4:217-26.

[21] InEK – Institut für das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus. Hinweise zur Leistungsplanung/Budgetverhandlung für 2010. 2009. Available from: http://www.gdrg.de/cms/index.php/inek_site_de/G-DRG-System_2010/Hinweise_zur_Leistungsplanung_Budgetverhandlung/Hinweise_zur_Leistungsplanung_Budgetverhandlung_fuer_2010

[22] Burchardi H, Specht M, Braun J, Schleppers A, Martin. OPS-Code 8-980 „Intensivmedizinische Komplexbehandlung“. 2004. Available from: http://www.dgai.de/downloads/OPS-Statement_03_11_2004.pdf

[23] Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270(24):2957-63.

[24] Miranda DR, de Rijk A, Schaufeli W. Simplified Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System: the TISS-28 items – results from a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(1):64-73.

[25] Parviainen I, Herranen A, Holm A, Uusaro A, Ruokonen E. Results and costs of intensive care in a tertiary university hospital from 1996–2000. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48(1):55-60. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00257.x

[26] DIMDI. OPS Version 2010 – Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel Version 2010. 2010;8/97-8. Available from: http://www.dimdi.de/static/de/klassi/prozeduren/ops301/opshtml2010/block-8-97...8-98.htm

[27] Green A, Williams A. Staff experiences of an early warning indicator for unstable patients in Australia. Nurs Crit Care. 2006;11(3):118-27. DOI: 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2006.00163.x

[28] Pronovost PJ, Miller MR, Dorman T, Berenholtz SM, Rubin H. Developing and implementing measures of quality of care in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7(4):297-303. DOI: 10.1097/00075198-200108000-00014

[29] Martín MC, Cabré L, Ruiz J, Blanch L, Blanco J, Castillo F, Galdós P, Roca J, Saura RM; Grupos de trabajo de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva Crítica y Unidades Coronarias (SEMICYUC), Sociedad Española de Enfermería Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias (SEEIUC) and Fundación AVEDIS Donabedian (FAD). Indicadores de calidad en el enfermo critico. Indicators of quality in the critical patient. Med Intensiva. 2008;32(1):23-32.

[30] Kastrup M, von Dossow V, Seeling M, Ahlborn R, Tamarkin A, Conroy P, Boemke W, Wernecke KD, Spies C. Key performance indicators in intensive care medicine. A retrospective matched cohort study. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1267-84.

[31] Rothen HU, Stricker K, Einfalt J, Bauer P, Metnitz PG, Moreno RP, Takala J. Variability in outcome and resource use in intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(8):1329-36. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-007-0690-3

[32] Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Timsit JF, Pochard F, Chevret S, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):698-704. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC

[33] Reader TW, Flin R, Mearns K, Cuthbertson BH. Developing a team performance framework for the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1787-93. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819f0451

[34] Oliveira J. The balanced scorecard: an integrative approach to performance evaluation. Healthc Financ Manage. 2001;55(5):42-6.

[35] Vagts DA, Bauer M, Martin J. (Un-)Sinn von Zertifizierung in der Intensivmedizin. Problematik der Detektion geeigneter Indikatorsysteme [The (non)sense of certification in intensive care medicine. The problem of the detection of suitable indicator systems]. Anaesthesist. 2009;58(1):81-7. DOI: 10.1007/s00101-008-1465-0

[36] Savel RH, Goldstein EB, Gropper MA. Critical care checklists, the Keystone Project, and the Office for Human Research Protections: a case for streamlining the approval process in quality-improvement research. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(2):725-8. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819541f8

[37] Byrnes MC, Schuerer DJ, Schallom ME, Sona CS, Mazuski JE, Taylor BE, McKenzie W, Thomas JM, Emerson JS, Nemeth JL, Bailey RA, Boyle WA, Buchman TG, Coopersmith CM. Implementation of a mandatory checklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence-based intensive care unit practices. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2775-81. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a96379

[38] Gallesio AO, Ceraso D, Palizas F. Improving quality in the intensive care unit setting. Crit Care Clin. 2006;22(3):547-71, xi. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccc.2006.04.002

[39] Mende H. Unsere Intensivmedizin muss besser werden!. Arztebl Baden Wuerttemb. 2007;62(12):622-3.