The pediculated gastrocnemius muscle flap as a treatment for soft tissue problems of the knee – indication, placement and results

Boris Moebius 1Eike Eric Scheller 1

1 Evang. Krankenhaus Hubertus, Berlin, Germany

Abstract

With the increase of endoprosthetic knee replacements, there is also an increase of critical wounds to the knee due to a high incidence of soft tissue problems (ranging from wound healing defects to severe wound infections). The literature describes a general rate of soft tissue complications of up to 20%

Keywords

gastrocnemius muscle flap, soft tissue damage of the knee, prosthesis infections

Introduction

Wound healing defects and associated soft tissue damages are becoming more important in the orthopedic practice. This is due to the significant increase of prosthesis implantations [4], including knee prosthesis implantations and the demographic development of society. The demands on a long lifetime of the prostheses are consistently increasing due to the increasing life expectancy of the patients receiving prostheses. Standardizations in endoprosthetics, increased experience of surgeons and the further development of prostheses has led to the consistent improvement of long-term results and lifetime of artificial joints [5], [6] so that prostheses are implanted and replaced in younger patients as well. A secure and stable coverage with soft tissue is a basic requirement for good short-term and long-term results regarding the prosthesis. Without a sufficient coverage with vital soft tissue with a good blood supply, primary implant healing and primary wound healing are not possible. The risks of infection of the prosthesis and reduced capacity of the new joint exist. This is especially important for the knee because there is little soft tissue coverage in general which contributes to the increased risk for wound healing defects due to the surgical wound leading to a reduced blood supply. Transcutaneous measurements of oxygenation have shown that the level of oxygenation near the surgical scar necessary for wound healing is only reached after two to three days [7][. Besides the negative impact of the surgery itself on the primary wound healing, various other exogenous factors play a role in wound healing. The most important factors are rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, long-term cortisone intake, malnutrition, nicotine use, hypothyroidism and existing multiple scars in the area of the surgery [8], [9], [10].

Material and methods

Laing et al. [11] have described five stages of soft tissue defects after knee endoprosthetics 1992:

- Stage 0: Redness near the wound without wound dehiscence or development of necrosis

- Stage 1: Only superficial skin necrosis or tension blisters, deeper layers not affected; no fistula

- Stage 2: Extensive skin necrosis with fistula towards the knee, deeper layers of tissue not affected

- Stage 3: Joint fistula with dehiscence of deeper layers; a small part of the joint prosthesis is visible

- Stage 4 : Widespread tissue necrosis with wound dehiscence and visible prosthesis

For stages 0 and 1, a conservative treatment with fixation of the knee and bed rest for the patient is favoured and the soft tissue damage usually heals well without surgical treatment. For stage 2 and above, surgical measures are preferred. In stage 2, the superficial skin necrosis should be removed and temporary soft tissue coverage and vac-therapy should occur. A swab should be submitted for an antibiogram for subsequent antibiotic therapy. Permanent soft tissue coverage can occur in the case of asepsis. Depending on size, a split-skin (MESH-graft) or full-skin graft can be chosen.

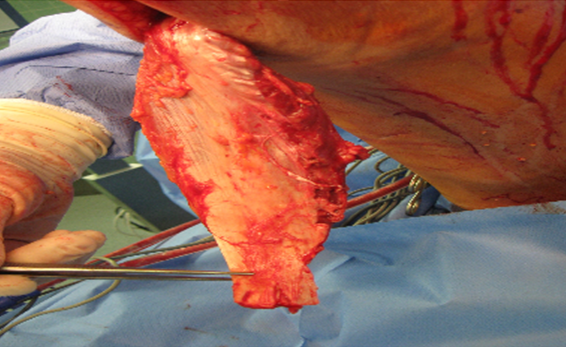

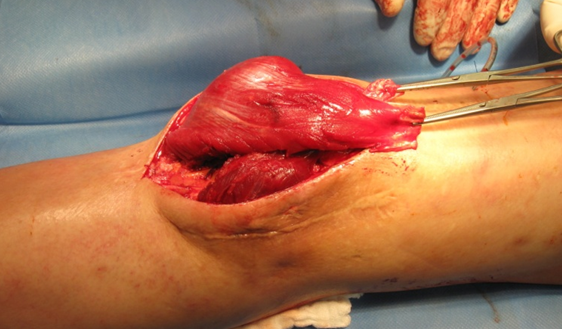

For soft tissue damage of stage 3 (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]), a muscle flap is necessary, because the deeper damages cannot be treated with mere skin transplants [12]. The benefits of muscle flaps, e.g. a gastrocnemius rotation flap, are evident: because the muscle flap is supplied with blood, it can be placed on infected wounds; this leads to a significant improvement of wound healing. This is due to secure soft tissue coverage of possibly exposed bone and prosthetic material. It is also due to the transportation of immunocompetent cells to the site of infection with the normal blood supply which leads to an improvement of wound healing and defence against infection [13]. For this stage, the elevation and use of one gastrocnemius muscle belly, medial or lateral, is sufficient (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]).

Figure 1: Stage 3 soft tissue damage according to Laing

Figure 2: Prepared medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle

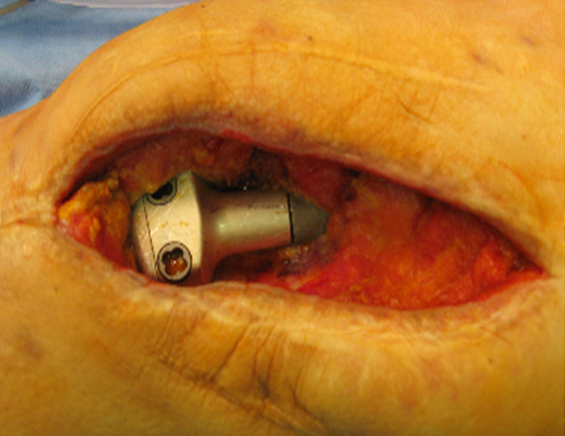

The lateral gastrocnemius muscle flap plasty was first described by Barford and Pers [14] and the medial gastrocnemius muscle flap plasty was first described by Ger [15]. The localisation of the damage dictates which muscle belly should be used. The medial head is often longer and wider than the lateral head which is why it is usually used. Due to separate blood supply through the Aa. surales medialis and laterialis, the elevation of an isolated flap [16] and the coverage of almost the entire knee (Figure 3 [Fig. 3]) is possible. The muscle belly should be lifted without a skin graft because this could cause problems with the closure of the skin near the location of extraction. For the dermal closure of the implanted muscle flap, split-skin (MESH-graft) with a thickness of 0.3 to 0.5 mm should be used. The muscular aponeurosis and parts of the fascia of the muscle should be removed, so that it can heal well (Figure 4 [Fig. 4]).

Figure 3: Inserted gastrocnemius

Figure 4: About three months after surgery

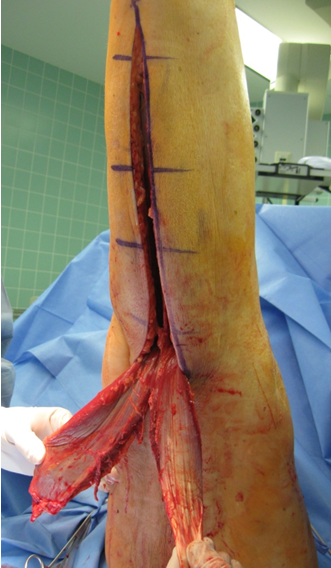

In case of stage 4 soft tissue damage, both bellies of the gastrocnemius muscle can be used. An area of up to 60 square centimetres can be covered this way [17]. The muscle coverage with split-skin (MESH-graft) is also indicated (Figure 5 [Fig. 5], Figure 6 [Fig. 6], Figure 7 [Fig. 7], Figure 8 [Fig. 8], Figure 9 [Fig. 9]).

Figure 5: Stage 4 soft tissue damaged according to Laing

Figure 6: After preparation of both muscle heads

Figure 7: After both muscle heads were pulled through

Figure 8: After fixation of both muscle heads

Figure 9: After split-skin graft on the gastrocnemius flap plasty

If there is an intact suralis muscle, the expected muscular deficit regarding plantar flexion is remarkably small [18], [19] and there is little aesthetic defect involved with muscle flap plasty [20].

Results

We treated 23 patients between 8/2004 and 3/2011 with a gastrocnemius muscle flap. 16 patients were treated for stage 3 soft tissue damage and seven patients were treated for stage 4 soft tissue damage. Accordingly, 16 patients received one-headed muscle flaps and seven patients received two-headed muscle-flaps with split-skin grafts from the ipsilateral thigh. Out of 23 patients, eight patients had to undergo surgery once more. Dehiscence or necrosis at the split-skin graft occurred in three patients, and this required repeated split-skin grafts. One patient experienced dehiscence near the extraction point of the muscle which was successfully treated with split-skin graft after vac-therapy. Four patients experienced recurring infection of the prosthesis with development of a fistula and large soft tissue destruction which was successfully treated with elaborate surgical measures in one case. The extremity could not be saved in three cases, and this resulted in above-knee amputation.

Conclusion

Due to the increasing number of implantation of knee endoprostheses and the associated number of soft tissue damages, a standardized procedure for the treatment of these complications is necessary. In the case of deep soft tissue damages with fistulas reaching the prosthesis or exposing the prosthesis, the gastrocnemius muscle flap is a good method for secure coverage of the prosthesis with well-perfused tissue. Despite the high rate of complications of almost 35% which required at least another surgery, the amputation of the extremity could be avoided for 87% of the treated patients. This method of soft tissue reconstruction is a necessary skill for surgeons involved with the implantation of knee endoprostheses.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Bruner S, Jester A, Sauerbier M, Germann G. Use of a cross-over fistula for simultaneus microsurgical tissue transfer and restoration of blood flow to the lower extremity. Microsurgery. 2004;24(2):114-7. DOI: 10.1002/micr.20005[2] Gerwin M, Rothaus KO, Windsor RE, Brause BD, Insall JN. Gastrocnemius muscle flap coverage of exposed or infected knee prothesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;286:64-70.

[3] Johnson DP, Bannister GC. The outcome of infected arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68(2):289-91.

[4] BARMER GEK. 3,5 Milliarden Euro für neue Knie- und Hüftgelenke. Report Krankenhaus. Berlin; Juli 2010.

[5] König A, Kirschner S. Langzeitergebnisse in der Knieendoprothetik [Long-term results in total knee arthroplasty]. Orthopäde. 2003;32(6):516-26.

[6] Erler K, Neumann U, Anders C, Venbrocks RA, Babisch J, Pieper KS, Scholle HC, Brückner L. Nachuntersuchungsergebnisse mittels EMG-Mapping – 5 Jahre nach Knieprothesenimplantation [5-Year Follow-up Study of Total Knee Arthroplasty by Means of EMG Mapping]. Z Ortop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2003;141(1):48-53. DOI: 10.1055/s-2003-37304

[7] Johnson DP. The effect of continuous passive motion on woundhealing and joint mobility after knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(3):421-6.

[8] Casanova D, Huard O, Zalta R, Bardot J, Magalon G. Management of wounds of exposed or infected knee prostheses. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2001;35(1):71-7. DOI: 10.1080/02844310151032637

[9] Nahabedian MY, Orlando JC, Delanois RE, Mont MA, Hungerford DS. Salvage procedures for complex soft tissue defects of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:119-24. DOI: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00017

[10] Ries MD. Skin nerosis after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(4 Suppl 1):75-7. DOI: 10.1054/arth.2002.32452

[11] Laing JH, Hancock K, Harrison DH. The exposed total knee replacement prosthesis: a new classification and treatment algorithm. Br J Plast Surg. 1992;45(1):66-9. DOI: 10.1016/0007-1226(92)90120-M

[12] Hallock GG. Salvage of total knee arthroplasty with local fasciocutaneous flaps. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(8):1236-9.

[13] Mathes SJ, Alpert BS, Chang N. Use of the muscle flap in chronic osteomyelitis: experimental and clinical correlations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(5):815-29. DOI: 10.1097/00006534-198205000-00018

[14] Barfod B, Pers M. Gastrocnemius plasty for primary closure of compound injuries of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 1970;52(1):124-7.

[15] Ger R. The technique of muscle transposition in the operative treatment of traumatic and ulcerative lesions of the leg. J Trauma. 1971;11(6):502-11. DOI: 10.1097/00005373-197106000-00007

[16] McCraw JB, Dibbel DG, Carraway JH. Clinical definition of independent myocutaneous vascular territories. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60(3):341-52.

[17] Li Z, Liu K, Lin Y, Li L. Lateral sural cutaneous artery island flap in the treatment of soft tissue defects at the knee. Br J Plast Surg. 1990;43(5):546-50. DOI: 10.1016/0007-1226(90)90118-J

[18] Markhede G, Nistor L. Strength of plantar flexion and function after resection of various parts of the triceps surae muscle. Acta Orthop Scand. 1979;50(6):693-7. DOI: 10.3109/17453677908991295

[19] Murray MP, Guten GN, Sepic SB, et al. Function of the triceps surae during gait; compensatory mechanism for unilateral los. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(4):473-6.

[20] Mathes SJ, Nahai F. Reconstructive Surgery: Principles, Anatomy and Technique. London/New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.