PTSD in adults with Mild Intellectual Disabilities: investigating the applicability of the trauma-focused art therapy protocol

Carolin Burkard 1Martina de Witte 2

Anna-Eva Prick 3,4

1 Siza, healthcare and support for people with a disability or chronic illness in the province Gelderland, Arnhem, Netherlands

2 University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

3 Department of Clinical Psychology, Open University, Heerlen, Netherlands

4 Department of Creative Arts Therapies, Zuyd Hogeschool, Heerlen, Netherlands

Abstract

Background and purpose: During the period 2002–2018, there was a steady increase of the diagnosis post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the Netherlands. Research shows that people with mild intellectual disability (MID) are significantly more often diagnosed with PTSD. This comorbidity is related to challenges in coping, cognitive and adaptive skills which in turn may increase the risk of PTSD. The treatment protocol “Trauma-focused art therapy for adults with PTSD” developed by Schouten and colleagues (Schouten et al. 2018) shows that it has potential for treating PTSD in adults with MID. Therefore, the aim of this qualitative practice-based research was to investigate the extent to which this protocol-based treatment matches the abilities and needs of adults with MID.

Method: Data was collected with multiple methods: from questionnaires (Delphi method), a focus group and from a single case study. The content was analyzed from the perspective of the client, the coordinating supervisor, and twelve professionals about the applicability of the Trauma-focused art therapy treatment protocol for adults with MID and PTSD.

Results: Seven recommendations for applying the protocol in adults with MID and PTSD were derived from the thematic analysis. These recommendations focus on personalized treatment, network-oriented work, adjusting the diagnostics, (contra)indications and therapist attitude, as well as modifying the sessions and the work formats.

Conclusion: The recommendations are consistent with national and international guidelines for trauma-focused interventions. The trauma-focused art therapy protocol therefore matches the needs of and can be applied to adults with MID and PTSD in clinical practice.

Keywords

art therapy, creative arts therapies, PTSD, trauma, mild intellectual disability, MID, Delphi method, focus group, single case

Introduction

Worldwide, it is increasingly reported that people with mild intellectual disabilities (MID) are significantly more likely to experience negative life events, abuse, and childhood trauma, compared to the general population [1]. In Dutch mental health care (Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg [GGZ]), four in ten clients are diagnosed with MID [2], of which one in five have MID combined with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3]. Approved trauma therapies, such as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), (imaginal) exposure and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) [4], [5] are effective treatments for people with MID [6]. However, these treatments require the client to verbally share and narrate his or her traumatic event(s). People with MID often experience difficulties verbalizing their memories specifically [7] while the body has recorded the memories and these memories can be felt by the client [8]. Embodied and experience-based therapy like art therapy may offer outcomes, such as the protocol of trauma-focused art therapy [9]. However, this protocol has not yet been tested for applicability in adults with MID. Given the high prevalence of PTSD in people with MID, there is great need to investigate the suitability of this protocol in this population. We used a qualitative research protocol to examine multidisciplinary treatment offerings for adults with MID and PTSD that can be optimized in clinical practice. This study lays a foundation for further research into the effectiveness of this protocol in this population.

In this article, we first discus the characteristics of MID and PTSD, then explain the current treatment standards for trauma treatment, and in addition the role of art therapy. The purpose and methods are explicitly formulated before describing the research process and the results on the possibilities of application of this protocol in adults with MID and PTSD.

Defining Mild Intellectual Disability (MID)

MID is defined as a neurobiological developmental disorder in which patients show a great extent of difficulties with their adaptive skills and cognitive development [10], [11]. Problems with adaptive skills also involve difficulties with (abstract) thinking, problem solving, or social situations [11]. These difficulties are particularly evident in the context of peers and culturally applied norms regarding behavior, nonverbal communication, habits, customs, and a stimulating environment [12]. In the Netherlands, the term MID is associated with a low intelligence quotient (IQ) of 50-85 with additional difficulties in adaptability towards a person’s environment [7]. People with an IQ between 70–85 are commonly described as borderline intellectual functioning (BIF) and are referred to in the literature as a distinct group within the MID [13]. In our study, one person with BIF was included, as his difficulty in social-adaptive functioning is equivalent to those with MID [14].

PTSD in people with MID

In the Netherlands and among many other countries, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is used to classify mental disorders. In its fifth edition, the DSM describes trauma and stressor-related disorders, including PTSD [15]. PTSD summarizes psychological complaints and disorders that arise after a major or shocking event [4], [15]. An interview protocol has been specifically designed for the diagnosis of PTSD in people with MID: the Diagnostic Interview Trauma and Stressors-MID (DITS-LVB) [16].

Wigham, Taylor and Hatton [17] followed people with MID for six months. They describe that potentially traumatic events are more common in people with MID. According to Mevissen et al. [18], over 80% of people with MID have experienced a traumatic event in their lives. Moreover, they are less able to process traumatic or shocking events because of their less well-developed cognitive and adaptive skills, increasing the risk of PTSD [19], [20]. Additionally, low intelligence is considered one of the six antecedent factors of PTSD [15], [21], [22], [23]. At 20%, PTSD appears to be the most common diagnosis in adults with MID [3]. According to Van Duijvenbode et al. [24], trauma treatment for adults with MID should include a focus on “doing and experiencing”, as experience-based learning better suits the abilities of this target group [25], [26].

Creative arts therapies

“Creative arts therapies” is the overarching term used for art therapy, dance-movement therapy, drama therapy, music therapy, psychomotor (child) therapy and play therapy in the Netherlands. They are particularly characterized by the clinical and evidence-informed use of the arts to accomplish individualized goals of clients within a therapeutic relationship in order to attune to physical, emotional, social, and cognitive needs [27]. Experience-based learning through partaking in specific exercises and forms of work is central to these therapies [28].

Art therapy

In art therapy (AT), art materials, tools, and techniques such as drawing, painting, clay, stone or woodwork are methodically employed by an art therapist. The client experiences sensory, emotional, and cognitive experiences that can lead to change and/or processing. According to the Federation of Professional Creative Arts Therapists [28], the distinctive feature of AT “is that the piece of work is concrete. The client can let go of that piece of work, put it away, reflect on it, and experience what it is like to do things differently”. However, in scientific research we found no information on AT for adults with MID and PTSD. According to Schrade et al. [29] AT can be supportive for people with MID in reducing stress and tension. Overall, it is stated that AT and making art promotes the adoption of different viewpoints [27], because the client is both the creator of the piece of work and can view the piece of work from a distance. Art-based self-expression and the creation of an artistic image increase both self-image and self-esteem, as the ability to express themselves promotes emotion regulation. In this way, clients learn to express and deal with emotions, get moving, make choices and regulate themselves [30], [31]. Self-shaping and experiencing with art materials counterbalances feelings of powerlessness and increases feelings of control and self-esteem [32], [33]. Creating pieces of artwork can be an effective way to communicate implicit information [34].

Art therapy in trauma treatment

In the Netherlands between 2015–2018, art therapy was used in 13% of clients with a main diagnosis of PTSD if they had not received cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or EMDR treatment for their PTSD symptoms [35]. The 2020 report by Zorginstituut Nederland [35] states that, “a proportion of people with PTSD do not choose trauma-focused therapy or are not suitable or able to follow trauma-focused therapy”. The report states that 30% of clients received neither CBT nor EMDR treatment. However, it does not give precise numbers of how many of these clients have a MID.

Adults who received trauma treatment unanimously stated that art therapy had had a positive effect on their trauma treatment, such as a stronger connection with their bodies [36]. Those surveyed were well-educated, four of whom were highly gifted. This raises the question of whether these effects can be generalized to people with MID.

Trauma-focused art therapy protocol

Within AT, trauma-focused art therapy was developed following preliminary research by Karin Alice Schouten in 2015 [37]. Trauma-focused art therapy is a treatment protocol in which eleven weekly treatment sessions of 60 minutes are offered in three phases. The goal is to reduce PTSD symptoms and strengthen the sense of control and self-confidence through a sensory and experiential intervention [9]. The design of the protocol is in line with contemporary international guidelines for trauma treatment, such as a clearly described treatment framework in terms of forms of work per session, a maximum of 12 treatment sessions, and a client’s insights into the treatment protocol [5].

Purpose and question

In trauma treatment for people with MID, attuned embodied and experience-focused therapy may offer positive outcomes for clients who appear to benefit more from a nonverbal approach. The purpose of this study was to examine the extent to which the protocol-based treatment of trauma-focused art therapy matches the abilities and needs of the MID client group.

The main research question is: How can the protocol-based trauma treatment for art therapy described by K. A. Schouten be applied within the trauma treatment of adults with MID and PTSD?

The following sub-questions are addressed:

- What adjustments do art therapists make to the protocol for treatment with adults with MID and PTSD?

- What promoting and impeding factors are reported by one client, the direct supervisor, and the performing art therapist after completing the AT intervention?

Method

Research design and type

Descriptive practice-based qualitative research delving into the experiences of professionals, a client, and their directional supervisor [38] was conducted to answer the research question. Using content analysis, themes and patterns from qualitative data were extracted through a systematic coding process [39]. Qualitative research methods were applied for each sub-question; these are explained in more detail below.

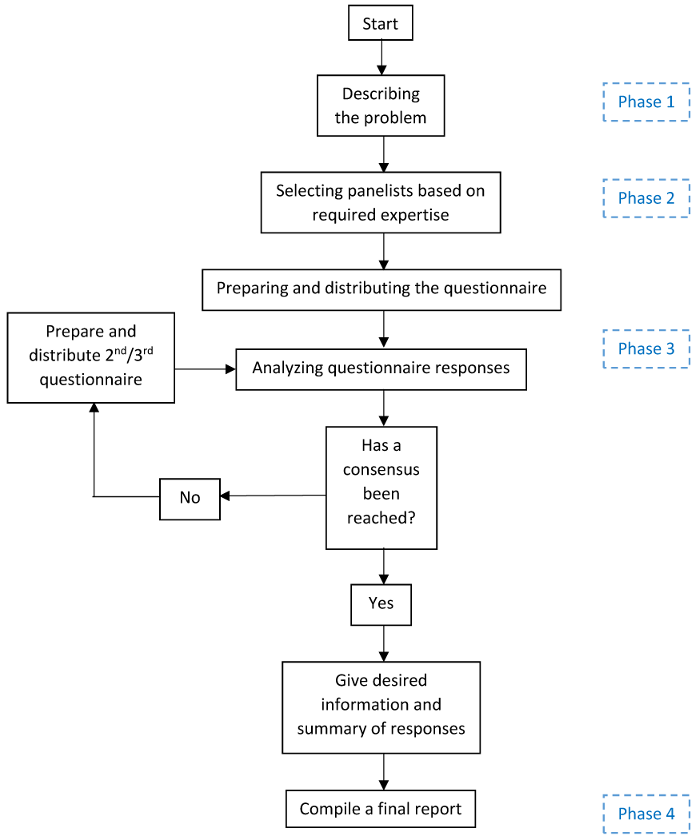

Sub-question 1: Delphi method and focus group

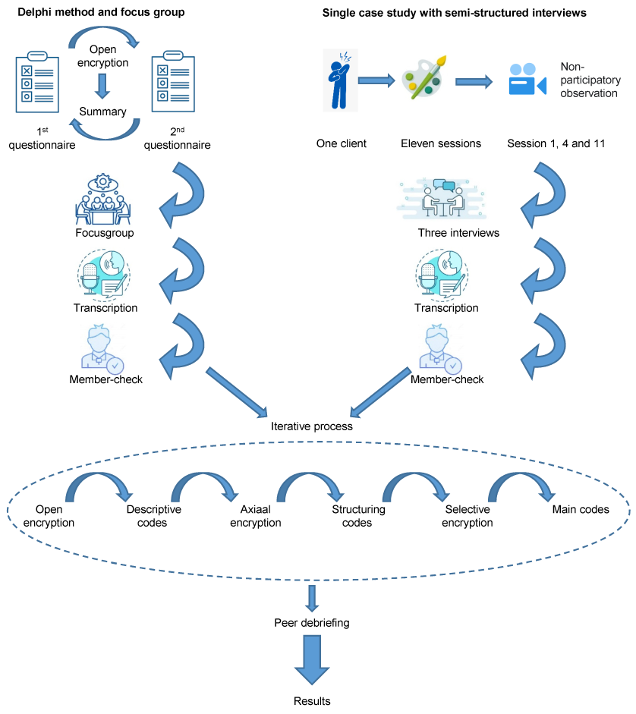

To answer the first sub-question, techniques from the Delphi method were employed. Designed in 1950 by RAND Cooperation [40], the Delphi method uses a cyclical process of questioning rounds and anonymously responding to each other’s answers until consensus is reached [41]. The cycle includes four stages (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]) in which the number of questioning rounds to reach consensus is not predefined [42]. The literature assumes at least two to three rounds are necessary [43], [44], [45]. The advantage of the Delphi method is that results are not influenced by group interaction, and that only the professional experiences lead to consensus. The disadvantage is that the researcher cannot specifically ask for details.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the four phases of the Delphi method [63]

Therefore, as a follow-up to the questionnaires, a focus group was chosen specifically ask about details that may not have been detected in the questionnaires. The conversation in the focus group was structured by the researcher using a checklist that emerged from the questionnaires [46]. Peer interaction in the focus group was stimulated by a moderator and provided new insights not yet addressed in the individual questionnaires [38].

Theoretical saturation was ensured by retrieving experiences first through the questionnaires and subsequently from the focus group, so that the statements made regarding the research question are valid.

Sub-question 2: Single case study with semi-structured interviews

To answer the second research question, a single case study using the current version of trauma-focused art therapy was implemented by an independent art therapist in practice. This helped identify specific experiences in the context of the protocol with relation to the question [41]. The case study was monitored by nonparticipant observation, followed by three separate semi-structured interviews held by the researcher after treatment ended. Respondents were not given predetermined response options [46]. The interviews thus provided space for the respondents’ own articulation of the perceived promoting and impeding factors during treatment [47].

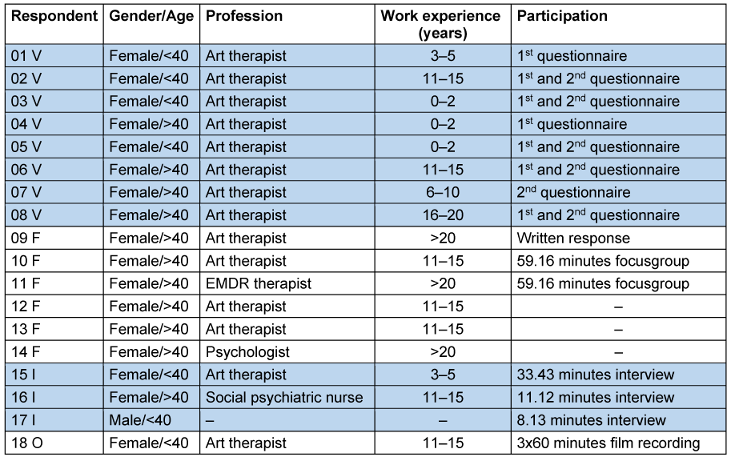

Research population

Study participants included twelve art therapists, one EMDR therapist, and one client and his directional supervisor. Respondents were recruited through social media, two peer review groups, and the researcher’s network.

Sub-question 1: Delphi method and focus group

For the questionnaires, we included art therapists who work with people with MID and are members of the Nederlandse Vereniging voor Beeldende Therapie (NVBT). Members of the NVBT are automatically registered members of the Federation of Professional Creative Arts Therapists (Federatie Vaktherapeutische Beroepen, FVB). This professional register sets requirements for vocational therapists, including education, work experience, continuing education, and training [48], so its members are considered competent in terms of knowledge and skills for this study. A second inclusion criteria was a minimum of one year of work experience with adults with MID and PTSD.

Inclusion criteria for participation in the focus group were that the art therapist and the EMDR therapist worked at different institutions and have conducted at least three trauma treatments with adults with MID and PTSD. The focus group consisted of a homogeneous group of experts in terms of knowledge about trauma treatment in adults with MID and PTSD. The experts constituted a heterogeneous group in terms of their field and expertise.

Sub question 2: Single case study with semi-structured interviews

Inclusion criteria for the single case study were that the participant was capable of giving informed consent, aged 18–65, had a mild intellectual disability according to the DITS-LVB, had been diagnosed with PTSD, and was on the waiting list for EMDR treatment. Additionally, the participant had a single trauma, had sufficient language skills and was socially and emotionally capable of handling the treatment and the interview. It was also important that his supervisor was willing to cooperate in the study.

The art therapist had to have at least one year of working experience with adults with MID and (online) be trained in the implementation of the protocol. Inclusion criteria for the non-participatory observer were an art therapist with at least one year of work experience.

Ethical justification

After approval by the research supervisor, the research proposal was reviewed for ethical issues by the Privacy Department of the recruiting institution involved. The research proposal was submitted to the committee on human-related research (CMO) Arnhem-Nijmegen to test whether it fell under the Medical Ethical Research Act (WMO). The CMO declared the study was not subject to the WMO (File number METC East Netherlands: 2022-13537).

Ethical aspects are safeguarded, as participation was voluntary, and an informed consent was signed in advance. The informed consent for the client was reviewed for understandable language so that it was easy for adults with MID to follow. The client was advised by the researcher to discuss participation in consultation with his caregivers and was given one week to gather questions. Possible questions were answered in a follow-up appointment; only then did the client sign for participation. All respondent data was pseudonymized and transcribed by the researcher. The research data in which participant data is traceable was stored only on secure equipment within the recruiting institution. The ICT department was contacted for this purpose. Questions regarding privacy were discussed with the data protection officer at the recruitment institution. To ensure respondent privacy, all data will be destroyed by the researcher no later than December 2022 [46].

The participating client retained rights to EMDR treatment and was contacted during the waiting period before the start of EMDR treatment. K. A. Schouten’s current protocol neither included nor excluded adults with MID and PTSD for trauma-focused art therapy. Therefore, it was considered plausible to offer this treatment to adults with MID and PTSD.

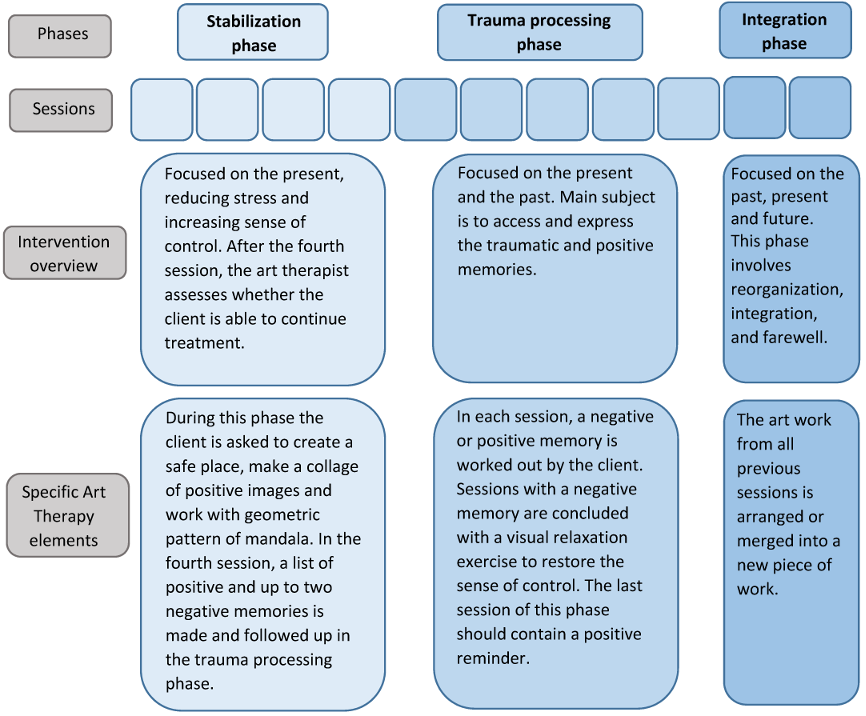

Intervention description

Schouten’s trauma-focused art therapy protocol is divided into three treatment phases [37]. The first phase, stabilization, has four sessions. These are followed by five sessions for trauma processing and two sessions for integration (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]). Each session lasts 60 minutes. Treatment was delivered in the client's natural environment, a treatment room at the recruitment facility.

Figure 2: Intervention outline

Procedure

The research took place between December 2021 and June 2022. During the research process, a logbook was kept by the researcher documenting the steps and considerations taken.

All respondents (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]) received prior information about the study as well as the protocol treatment description from the FVB database [49].

Table 1: Respondents’ characteristics

Sub-question 1: Delphi method and focus group

Eight art therapists received a questionnaire with 23 semi-structured questions related to the protocol treatment such as therapeutic posture, material supply and duration, amount, and frequency of one session. They were asked to return the completed questionnaire via mail within one week. Six respondents returned the complete questionnaire by the deadline, one returned it late, and one did not return the questionnaire. The responses were summarized by the researcher and resent to the eight respondents with the question of whether each agreed with this summary or if there were any further additions. Again, the response deadline was one week. Six respondents returned their questionnaires within the deadline, two respondents did not respond, even after a reminder.

In the follow-up, the data from the questionnaires were used for input to the 60-minute online focus group. The researcher created a checklist and shared it with the moderator for preparation purposes. The focus group took place online so that it could proceed independently of any measures taken due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Audio and video recordings were made of the entire discussion. Of the six respondents, two participated in the focus group, namely one art therapist and one EMDR practitioner. The absent respondents were given the choice of responding in writing to the focus group transcript, or conducting a separate interview. One respondent responded and provided a written response with her experiences regarding the statements from the focus group.

Sub-question 2: Single case study with semi-structured interviews

In parallel to the first two phases, the case-study client with MID and PTSD was treated according to the current trauma-focused art therapy protocol twice weekly. The executive art therapist was trained in advance online by K. A. Schouten for the implementation of the protocol. The researcher reviewed informed consent together with the client and administered the DITS-LVB. The directing therapist then discussed the informed consent with the client again the following week. After signing, the researcher connected the client, his directional supervisor, and the art therapist made arrangements for the start of treatment.

The first, fourth and eleventh sessions were videotaped by the art therapist. In the week after treatment ended, the video recordings were reviewed by non-participatory observers regarding whether the protocol had been correctly followed.

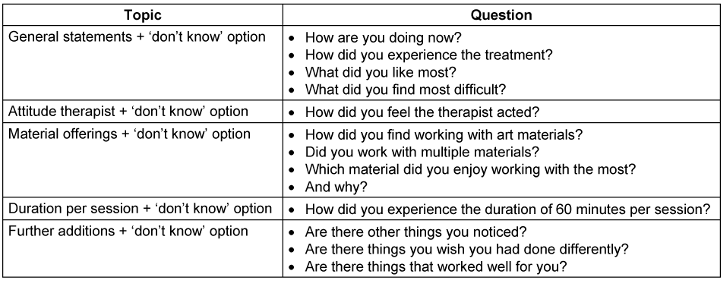

In the week after the eleventh session, the researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with the client, the directional supervisor, and the art therapist. The topic list for the interviews was related to the items of the treatment protocol, such as therapist attitude, material provision and duration, amount, and frequency of one session. The topic list for the client interview (Table 2 [Tab. 2]) was based on DITS-LVB preconditions such as attitude, response categories and visual support to meet the client’s possibilities for exploring experience [26]. Specific factors for interviews in adults with MID were applied. These included interviewing within one week of the end of treatment, limiting the number of response options, a sparing use of open-ended questions, and adding a “don’t know” option [50].

Table 2: Topic list of interview client

Analysis

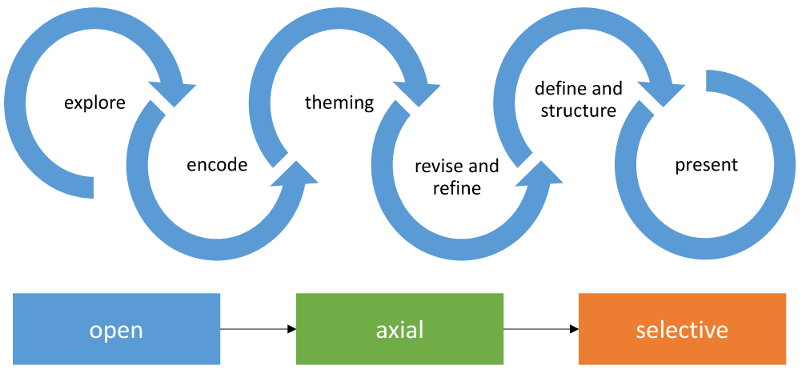

The unstructured data from the questionnaires, focus group and interviews were systematically analyzed and interpreted in six steps, as described in Figure 3 [Fig. 3], [51], [52].

Figure 3: Six steps of analysis [49]

Sub-question 1: Delphi method and focus group

Before coding the questionnaires and focus group data, a member-check was conducted with the respondents to ensure the accuracy of the summary [41]. The member-check of the questionnaires was based on the written summary of all responses. The focus group summary was based on the audio and video recording transcribed using Amberscript SaaS software [53].

Both summaries then were analyzed thematically, employing techniques from the framework approach according to Ritchie and Spencer [54]. Prior knowledge was combined with the research question and themes that emerged from the data collection. This data provided a framework for further coding, analysis, and interpretation [38], [55].

Sub-question 2: Single case study with semi-structured interviews

The case study audio recordings of the interviews were first transcribed using Amberscript [53]. The transcripts were then summarized through thematic analysis and sent to all respondents for member-check. The summary of the interview with the client was reviewed through peer debriefing because the client was unable to review the summary. The observation was not included in the analysis because its purpose was to monitor the actual treatment.

All questionnaire summaries and focus group and interview transcripts were then coded using ATLAS.ti data analysis software [56]. Coding occurred in an iterative process in which data collection and analysis alternated [38]. The iterative process is a mark of quality for the reliability of the results [38]. The iteration proceeded in three phases starting with an open exploration using descriptive codes (exploration phase with open coding) to look for structure and structuring codes in a more focused way (specification phase with axial coding) and then creating more coherence through pattern codes (reduction phase with selective coding) [57]. The reflection on answering the research question simultaneously served as input for the next cycle [38]. The researcher repeated this process until a reliable answer to the research question could be provided [38].

After analysis, the findings were peer-debriefed by an independent trainee researcher to review all aspects and assumptions [58]. Figure 4 [Fig. 4] provides a visual representation of the analysis process.

Results

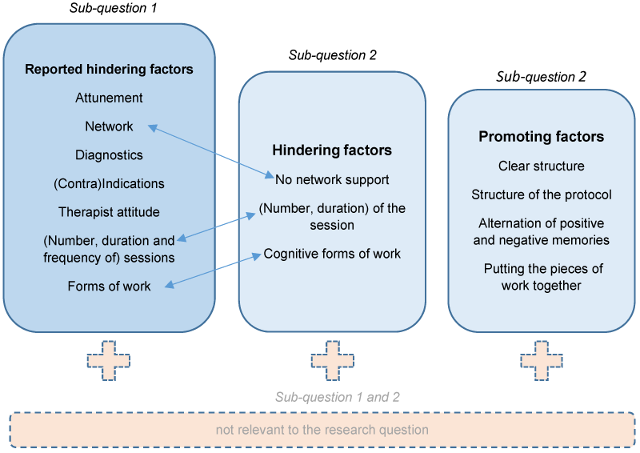

During open coding, 499 descriptive codes were assigned to the data and then ordered into 95 structuring codes in axial coding. After selective coding, eight topic codes were identified for sub-question 1: alignment, system, diagnostics, (contra)indications, therapist attitude, (number, duration, and frequency of) sessions, forms of work, and codes not relevant to the research question.

For sub-question 2, five topic codes were identified during selective coding for promoting factors: clarity, structure, positive and negative memories, merging in the integration phase, network, and codes not relevant to the research question. For impeding factors, four theme codes emerged: network, (number, duration, frequency of) sessions, forms of work, and codes not relevant to the research question.

Codes that fell under the theme code “not relevant to the research question” were not included in the results as they did not answer the research question.

Sub-question 1: Delphi method and focus group

Using the Delphi method and the focus group, experiences were collected regarding the question of what adaptations art therapists indicate in the protocol for the treatment of adults with MID and PTSD.

From the responses to the two questionnaires and the focus group, two main themes emerged, identified by all respondents as important factors for trauma treatment in adults with MID.

- Attunement: All respondents indicated that attunement to the process of the individual client with MID and PTSD should be leading when implementing the protocol. Attunement to the client is seen as a prerequisite to getting and staying in collaboration. Here, particular emphasis is placed on being able to see and intervene on what occurs in the visual work. For example, an art therapist indicated that it is important to “find the balance between providing clarity and structure on the one hand and following the client and allowing space if appropriate on the other. So always seeing and feeling what is needed and being able to connect to that, protocol or not”.

- Network: All respondents indicated that working systemically and involving the network is very important when implementing this protocol in adults with MID and PTSD. Some respondents indicated that the treatment described as a separate treatment discipline for adults with MID and PTSD is inadequate. According to all respondents, a network approach is necessary because often there is more going on in this client group. Adults with MID and PTSD are, according to respondents, a vulnerable group in society, so involving the network and careful consultation with the home situation, supervisors and other treatment providers is important. This allows the client to experience moments of regulation outside of therapy, and stabilizing factors are deployed so that the client dares enter treatment. An art therapist stated, “If there is insufficient support from the client or his network, successful treatment is not possible.“

In addition, five themes focusing on the current protocol were suggested as modifications.

- Diagnostics in MID for PTSD: The current protocol uses the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) for diagnosing PTSD. Some respondents mentioned the need to use specific measurement tools for diagnosing PTSD in adults with MID. It is important to match the abilities of this client group in language and by using visual support. According to one EMDR therapist, “the DITS-LVB is perhaps even more differentiated for pre-measurement than the HTQ.”

- (Contra)Indications: The indication criteria from the protocol were recognized by all respondents. A few indicated that specifically for AT, the client must have some motivation for the treatment and affinity with the discipline must be present. According to these respondents, these criteria are usually considered by the primary practitioner prior to referral.

Regarding the current protocol contraindication criteria, some respondents indicated that a psychosis or severe depression were precisely reasons to initiate trauma treatment and they did not recognize themselves in this contraindication. Moreover, a high degree of suicidality is not a direct contraindication according to most respondents, but it does require close cooperation with the system. One art therapist indicated that there are no contraindications in cases of PTSD in adults with MID because “if there is PTSD, what the client is experiencing in his head is already bad; you can hardly make it worse.” - Therapist attitude: The current protocol describes the therapist’s attitude as directive, as the art therapist manages care of clarity and structure and offers space and facilitates so that clients can express themselves in the art work. All respondents agreed with this. Several respondents also mentioned specific qualities that the art therapist must have for the treatment of adults with MID and PTSD. One stated that, “a stable healthy adult side with awareness of one’s own attitude towards trauma in order to attune constructively to the client and oneself is important”. Associated with this are (self)compassion and a mentalizing ability in which the therapist is inviting and calm, in addition to being directive.

- (Number, duration, and frequency of) sessions: Experiences were divided regarding the specific items of the protocol, such as number, duration, and frequency of sessions. Most felt that there were too few sessions. In adults with MID, trauma emerges gradually during the treatment process because this client group needs a longer processing time. Some therefore recommended that treatment should not be strictly limited to 11 sessions. What all respondents agreed on was that two sessions for the integration phase are too few.

Most respondents felt that the session length of 60 minutes per session was not feasible. They indicated that a session length of 90 minutes would better suit the needs of the client group. According to them, the steps in the session for adults with MID and PTSD should be smaller. Some respondents indicated that one session could also be less than 60 minutes, as it is important to see what a client with MID and PTSD can do and cope with.

Regarding frequency, most respondents felt that weekly sessions, as described in the current protocol, are feasible for adults with MID. One respondent indicated that art therapy should be scheduled every second week given the delayed processing time in adults with MID and PTSD. A few other respondents felt this was not practical because then the process would stagnate. As a possible adjustment, most indicated that twice a week would be optimal as recent research has provided evidence for the benefits of short-term intensive treatment. An art therapist stated, “the moment you make the frequency a little more intensive, you can also cycle through the pictures a little faster”. - Forms of work: Most respondents found reflective work-forms, as making a safe place or a collage of positive images, inappropriate in adults with MID and PTSD. For the stabilization phase, most respondents described themes of work that focused on safety, an introduction and experimentation with the material as described in the protocol. But respondents prefers to work through art as therapy, in which it is not the product created but the path to it that is more central. Some felt that offering relaxation exercises such as a body scan was important in the trauma processing phase; others emphasized that the relaxation exercises as described in the protocol must be art-based to be offered within art therapy.

Sub-question 2: Single case study with semi-structured interviews

Based on the three individual semi-structured interviews with the client, the directional supervisor and the art therapist, experiences regarding the question of which promoting and impeding factors are reported.

- Promoting factors: All interviewees indicated that the clear construction and structure of the protocol were conducive to the treatment. This provided clarity and therefore security for the client to enter treatment. The alternation of positive and negative memories was experienced as positive by all respondents. The art therapist stated, “in this way, the client does not get stuck in negative memories but can put them into perspective by also looking at positive memories“. Most respondents indicated that putting the pieces of work together in the integration phase was helpful to bring closure to the process. For example, the art therapist noted, “it joined everything he has been working on into one orderly piece of work.”

- Impeding factors: The art therapist, as well as the directional supervisor, indicated that closer cooperation and handover would have been desirable. Involving the network would have been important to support the client. The directional supervisor said, “the more feedback, the more consultation; more tools to pick up and move forward with the client. Precisely because it’s so important to the client.”

About the number, duration and frequency of the session, the art therapist and the directional supervisor indicated that the number of sessions was too few. The client said, “it was just fine like this. I do want to continue therapy and then move towards the future.” All respondents indicated that the duration of 60 minutes was not appropriate. Especially in the trauma processing and integration phases, more time was required per session. For example, the art therapist noted, “[...] coordination is more important here than cutting off the process.”

In addition, the art therapist indicates that the work-forms were adapted for the client regarding language level because they depended too much on cognitive ability. The art therapist said, “The client had to think and process what I was asking and translate it into an action.”

Figure 5 [Fig. 5] presents the theme codes from sub-question 1 and 2. The relation of the retrieved experiences is indicated with blue arrows.

Figure 5: Visual representation of results

Discussion

This qualitative study has provided information from several perspectives on the possibilities of how the art therapy trauma treatment protocol described by K. A. Schouten can be applied to the trauma treatment of adults with MID and PTSD.

Sub-question 1: Delphi method and focus group

The results show that personalized, tailored treatment in collaboration with the system is a prerequisite for successful treatment outcome in adults with MID and PTSD. In addition, five modifications are given regarding diagnostics, (contra)indications, therapist attitude, (number, duration, and frequency of) sessions, and work-forms. In a literature review, Luteijn [59] endorses involving the network adjusting the therapist's attitude, session structure, and measuring instruments in the trauma treatment of adults with MID.

Sub-question 2: Single case study with semi-structured interviews

Four promoting factors of the current protocol for adults with MID and PTSD emerged from the interviews. The clear construction, the structure, the alternation of positive and negative memories, as well as the merging of work pieces in the integration phase are described as positive. The lack of involvement of the network, the number and duration of sessions and the cognitive work formats were mentioned as impeding factors. It is worth noting that treatment frequency was increased to twice weekly in this study as it was expected that this would better suit the abilities of the client with an MID [25], [26], [60]. Therefore, it is possible that the frequency of sessions was not mentioned as a perceived impeding factor. However, respondents to sub-question 1 gave different answers about the possible frequency of AT, and this expectation will have to be retested in further research. Nonetheless, the results of the current study regarding the client perspective should be cautiously considered because only one client was observed in this study.

Lessons learned

Remarkable results in this study concerned the results from sub-questions 1 and 2 are the common themes mentioned, such as the added value of a network approach, broadening the number and duration of sessions, and adjusting the work-forms. Themes such as involving parents and supervisors, giving more time for the treatment process, and offering work-forms in a less reflective form are confirmed in the literature [61].

What did not emerge from the research but is reported in the literature as an overarching factor in the treatment of adults with MID and PTSD, is the therapeutic working relationship [59]. According to Douma [25], establishing a good working relationship is a prerequisite for an intervention to succeed with this client group. The success of an intervention depends less on the intervention itself than on ‘common factors’, such as the quality of the working relationship [62]. The adaptation ‘therapist attitude’ that art therapists indicated on sub-question 1 refers to this, describing a mentalizing attitude. However, how the working relationship contributes to successful treatment remains unknown [63].

Strengths and limitations of the study

Retrieving experiences from various perspectives with respect to the question posed was central to this study. By including experiences of one client, someone in the client’s network, and professionals in this study, different perspectives were included in answering the question. Because of the national distribution and variation in work experience and function of the professionals, and the corresponding themes regarding the recommendations (saturation), the retrieved experiences are generable. Moreover, in all phases the data were checked for accuracy through member-check and peer debriefing. This ensured the researcher’s objectivity.

A possible limitation is whether the interview with the client provided a sufficiently reflective answer to the question, as one of the protocol’s indication criteria is that people have difficulty verbalizing. This limitation was accounted for by pre-structuring the interview with the client by means of topics. However, this may have resulted in less retrieval of the client’s actual experiences, while qualitative research aims to make this more explicit.

In addition, fewer respondents participated in the focus group than registered. According to Boendermaker et al. [64], the optimal group size for a focus group is at least six participants in order to stimulate discussion from different points of view and mutual interaction. This makes the term focus group less applicable, and the information retrieved could be said to be from a group interview in which six topics were discussed in three clustered topics.

Finally, it is important to note that the respondents from sub-question 1 did not have the full protocol (workbook) available, but only a product description explaining each phase and the working methods per phase (see Figure 2 [Fig. 2]) of treatment but not each session. In consultation with the protocol’s author (Schouten), the whole workbook could not be shared because respondents would have had to receive training to do so. At the time of the study, no training for this protocol had yet been set up. However, the art therapist and the researcher were trained online in advance so that the workbook could still be applied in treatment.

Future research

This study can be extended to include multiple cases to provide a more comprehensive picture of the experience. As follow-up, a quantitative pilot study, perhaps with the single case experimental design (SCED) should address the effect of the indicated modifications.

Conclusions

This research descriptively answers the main question of how trauma-focused art therapy can be applied for trauma treatment in adults with MID and PTSD.

The collected data in this study involving one client, professionals, and relatives provides a picture of experiences in the context of the research question. It should be noted, however, that a single case study does not permit generalizing statements to be formulated about how trauma-focused art therapy is experienced by adults with MID and PTSD. On the other hand, by involving the client’s perspective, this study followed the ‘participatory approach’, referring to clinical initiatives being evaluated and improved based on knowledge and experiences of its current users [65]. This aligns with the call for knowledge democratization to hear their voices on research that affect them [66], [67].

Based on the theoretical concepts described in the introduction, the experiences gleaned from this study indicate that, in addition to the experiential approach, other factors, as described by the respondents, are considered important in trauma treatment for people with MID. These recommendations are in line with national and international guidelines for trauma-focused interventions [4], [5] where protocol-based treatment of up to 12 sessions is recommended, but more can be deployed if clinically indicated and the alignment with the client, as well as the involvement of the network are mentioned.

The results show that the trauma-focused art therapy protocol, after modification with the seven recommended factors, can be applied in adults with MID and PTSD in clinical practice. In the future, it is recommended that this study be expanded to include multiple cases to provide a more comprehensive picture. As a follow-up, quantitative research with perhaps more suitable designs like the SCED, can further address the effects of the indicated modifications.

Notes

Statement of interest

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Dion J, Paquette G, Tremblay KN, Collin-Vézina D, Chabot M. Child Maltreatment Among Children With Intellectual Disability in the Canadian Incidence Study. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018 Mar;123(2):176-88. DOI: 10.1352/1944-7558-123.2.176[2] Douma J, Nieuwenhuis J. LVB en psychiatrie. Landelijk Kenniscentrum LVB. Overzciht van Informatiebronnen. Utrecht: LVB; 2021. Available from: https://www.kenniscentrumlvb.nl/product/informatiebronnen-lvb-en-ggz-2/

[3] Wieland J, Kapitein S, Otter M, Baas RW. Diagnostiek van psychiatrische stoornissen bij mensen met een (zeer) lichte verstandelijke beperking [Diagnosing psychiatric disorders in people with (very) mild intellectual disabilities]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2014;56(7):463-70. Dutch

[4] GGZ Standaarden. Psychotrauma – en stressorgerelateerde stoornissen. 2024 Jun 25. Available from: https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/zorgstandaarden/psychotrauma-en-stressorgerelateerde-stoornissen/individueel-zorgplan-en-behandeling/behandeling-en-begeleiding/behandelstroomschema-van-ptss

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chapter Recommendations, 1.6 Management of PTSD in children, young people and adults. In: Post-traumatic stress disorder NICE guideline [NG116]. NICE; 2018 Dec 05 [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/chapter/Recommendations#management-of-ptsd-in-children-young-people-and-adults

[6] Struik A, van Blanken B. Traumabehandeling kan wel! De toepassing van de slapende honden methode bij jeugdigen en volwassenen met een verstandelijke beperking. LVB Onderzoek & Praktijk. 2018;16(1):5-17.

[7] MEE Zuid-Holland Noord. LVB-ers die uit balans zijn. Hoe herken je ze, hoe ga je ermee om? Sociaal-emotioneel functioneren bij mensen met een licht verstandelijke beperking. Delft: MEE Zuid-Holland Noord; 2015 Sep. Available from: http://www.lvbinamsterdam.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/LVB-ers-die-uit-balans-zijn.-Hoe-herken-je-ze-hoe-ga-je-er-mee-om.pdf

[8] van der Kolk B. How trauma lodges in the body. National Public Radios On Being; 2017.

[9] Schouten KA. Trauma-Focused Art Therapy. Individuele, poliklinische beeldende therapie gericht op het verminderen van PTSS klachten (vermijding, arousal en herbeleving) en het versterken van zelfvertrouwen en gevoel van controle bij volwassenen met PTSS. In: Databank Vaktherapie; 2020 Apr 20.

[10] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. DOI: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

[11] Kenniscentrum LVB. Wat is LVB? [cited 2022 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.kenniscentrumlvb.nl/wat-is-lvb/

[12] Kaldenbach Y. Betekenis verlenen aan test-hertest verschillen bij intelligentieonderzoek. VVP nieuws. 2012;18:10-4.

[13] GGZ Standaarden. Psychische stoornissen en ZB/LVB Psychische stoornissen en zwakbegaafdheid (ZB) of lichte verstandelijke beperking (LVB). 2023 Mar 15. Available from: https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/generieke-modules/psychische-stoornissen-en-zwakbegaafdheid-zb-of-lichte-verstandelijke-beperking-lvb/introductie

[14] Zorginstituut Nederland. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: http://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl

[15] American Psychiatric Association. Beknopt overzicht van de DSM-5. Amsterdam: Boom; 2014.

[16] Accare. DITS-LVB Download dit klinisch interview. [last updated 2024 May 26, cited 2021 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.accare.nl/child-study-center/kennisdomein/dits-lvb

[17] Wigham S, Taylor JL, Hatton C. A prospective study of the relationship between adverse life events and trauma in adults with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2014 Dec;58(12):1131-40. DOI: 10.1111/jir.12107

[18] Mevissen EHM, Didden HCM. Systeemgerichte diagnostiek en behandeling van psychotrauma bij jeugdigen met een licht verstandelijke beperking. Onderzoek & Praktijk. 2017 Jan 1;15:6-14.

[19] Mevissen EHM, Didden HCM, de Jongh A. EMDR voor trauma- en stressorgerelateerde klachten bij patiënten met een verstandelijke beperking. Dth-Kwartaalschrift voor Directieve Therapie en Hypnose. 2016 Jan 1;36:5-26.

[20] van Kregten C, Knipschild R, Mevissen L, Katee M, van Nieuwenhuizen M, Prins P, Appelboom K, Neumann C, ter Avest R. Tijdig signaleren en behandelen van trauma- en stressorgerelateerde problemen bij jeugdigen en jongvolwassenen met een licht verstandelijke beperking. Utrecht: Academische werkplaats Kajak; 2020.

[21] Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000 Oct;68(5):748-66. DOI: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748

[22] DiGangi JA, Gomez D, Mendoza L, Jason LA, Keys CB, Koenen KC. Pretrauma risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013 Aug;33(6):728-44. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.002

[23] Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014 Sep;59(9):460-7. DOI: 10.1177/070674371405900902

[24] van Duijvenbode N, Klein Snakenborg J, de Haan H, Roeleveld E, Nieuwold M, van der Nagel J. Seeking Safety voor mensen met een LVB. Addendum bij Seeking Safety voor de toepassing bij mensen met een lichte verstandelijke beperking. Deventer: Tactus Verslavingszorg; 2021.

[25] Douma J. Jeugdigen en (jong) volwassenen met een licht verstandelijke beperking. Kenmerken en gevolgen voor diagnostisch onderzoek en gedragsinterventies. Utrecht: Landelijk Kenniscentrum LVB; 2018.

[26] de Wit M, Moonen X, Douma J. Richtlijn Effectieve Interventies LVB: Aanbevelingen voor het ontwikkelen, aanpassen en uitvoeren van gedragsveranderende interventies voor jeugdigen met een licht verstandelijke beperking. Utrecht: Landelijk Kenniscentrum LVB; 2011. Available from: https://www.kenniscentrumlvb.nl/product/richtlijn-effectieve-interventies-lvb-gedrukte-uitgave/

[27] de Witte M, Kooijmans R, Hermanns M, van Hooren S, Biesmans K, Hermsen M, Stams GJ, Moonen X. Self-Report Stress Measures to Assess Stress in Adults With Mild Intellectual Disabilities-A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:742566. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.742566

[28] Vaktherapie. Beeldende therapie. [cited 2021 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.vaktherapie.nl/beeldende-therapie

[29] Schrade C, Tronsky L, Kaiser DH. Physiological effects of mandala making in adults with intellectual disability. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2011 Apr;38(2):109-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2011.01.002

[30] Haeyen S, van Hooren S, Hutschemaekers G. Perceived effects of art therapy in the treatment of personality disorders, cluster B/C: A qualitative study. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2015 Sep;45(45):1-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2015.04.005

[31] Bosgraaf L, Spreen M, Pattiselanno K, van Hooren S. Art Therapy for Psychosocial Problems in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Narrative Review on Art Therapeutic Means and Forms of Expression, Therapist Behavior, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change. Front Psychol. 2020;11:584685. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584685

[32] Spiegel D, Malchiodi C, Backos A, Collie K. Art Therapy for Combat-Related PTSD: Recommendations for Research and Practice. Art Therapy. 2006 Jan;23(4):157-64. DOI: 10.1080/07421656.2006.10129335

[33] Wertheim-Cahen T. De rol van vaktherapieën bij de behandeling van psychotrauma. In: Aarts PGH, Visser WD, editors. Trauma: diagnostiek en behandeling. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2007. p. 313-28.

[34] Gerge A. What does safety look like? Implications for a preliminary resource and regulation-focused art therapy assessment tool. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2017 Jul;54:105-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.04.003

[35] Zorginstituut Nederland. Zinnige Zorg bij PTSS – verbetersignalement. Zorginstituut Nederland. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: http://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl

[36] Meijnckens D, Hesselink A. Achterbanraadpleging Zorgstandaard Trauma- en stressorgerelateerde stoornissen. Harleem: 2016 Jul. Available from: https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/uploads/side_products/c4f88ad23e8e0e760b264eb927b59651.pdf

[37] Schouten KA, van Hooren S, Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ, Hutschemaekers GJM. Trauma-Focused Art Therapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Pilot Study. J Trauma Dissociation. 2019;20(1):114-30. DOI: 10.1080/15299732.2018.1502712

[38] Verhoeven N. Wat is onderzoek?: praktijkboek voor methoden en technieken. Amsterdam: Boom; 2018.

[39] Cho JY, Lee EH. Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. Qualitative report. 2014:19-32. DOI: 10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1028

[40] RAND. A Brief History of RAND. [cited 2022 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/about/history.html

[41] Baarda B, Bakker E, Julsing M, Fischer T, van Vianen R. Basisboek methoden en technieken: kwantitatief praktijkgericht onderzoek op wetenschappelijke basis. Groningen: Noordhoff Uitgevers; 2017.

[42] Linstone HA, Turoff M. Introduction. In: Linstone HA, Turoff M, editors. The Delphi Method Techniques and Applications. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. p. 3-12.

[43] Elliott J, Heesterbeek S, Lukensmeyer CJ, Slocum N. Participatieve methoden: een gids voor gebruikers. Brussels: Vlaams Instituut voor Wetenschappelijk en Technologisch Aspectenonderzoek, Vlaams Parlement; 2006.

[44] Kieft M. De delphi-methode nader bekeken. Nijmegen: Samenspraak Advies; 2011.

[45] Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000 Oct;32(4):1008-15.

[46] Bakker EC, van Buuren H. Onderzoek in de gezondheidszorg. Groningen: Noordhoff Uitgevers; 2019.

[47] Evers J, de Boer F. The qualitative interview: Art and skill. Den Haag: Eleven international publishing; 2012.

[48] Register Vaktherapie. [cited 2021 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.registervaktherapie.nl/

[49] Schouten KA. Federatie Vaktherapeutische Beroepen. Trauma-Focused Art Therapy. Individuele, poliklinische beeldende therapie gericht op het verminderen van PTSS klachten (vermijding, arousal en herbeleving) en het versterken van zelfvertrouwen en gevoel van controle bij volwassenen met PTSS. In: Databank Vaktherapie. 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 02]. Available from: https://www.databankvaktherapie.nl/bekijk/183962/Trauma-Focused-Art-Therapy.-Individuele

[50] de Witte M, Kooijmans R, Hermanns M, van Hooren S, Biesmans K, Hermsen M, Stams GJ, Moonen X. Self-Report Stress Measures to Assess Stress in Adults With Mild Intellectual Disabilities-A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:742566. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.742566

[51] Plochg T, Juttmann RE, Klazinga NS, Mackenbach JP, Giard RWM. Handboek gezondheidszorgonderzoek. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2006.

[52] Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

[53] Amberscript Global B.V. Audio en video omzetten in tekst binnen enkele minuten. Amberscript. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.amberscript.com/nl/producten/automatische-transcriptie/

[54] Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Huberman AM, Miles MB, editors. The qualitative researcher's companion. London: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2002. p. 305-29. DOI: 10.4135/9781412986274.n12

[55] Van Staa A, de Vries K. Directed content analysis: een meer deductieve dan inductieve aanpak bij kwalitatieve analyse. Kwalon. 2014;19(3):46-54.

[56] Atlas.ti. A brief history of ATLAS.ti. [cited 2022 Feb 14]. Available from: https://atlasti.com/product/what-is-atlas-ti/

[57] Hagen D. Kwalitatief Onderzoek Transcriberen en analyseren. Intern powerpoint document. Amsterdam: Hogeschool van Amsterdam; 2018.

[58] Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985.

[59] Luteijn I, van der Nagel JEL, van Duijvenbode N, de Haan HA, Poelen EAP, Didden R. Behandeling van posttraumatische stressstoornis en een stoornis in middelengebruik bij cliënten met een licht verstandelijke beperking. Tijdschrift voor Artsen voor Verstandelijk Gehandicapten. 2020;38(4):215-22.

[60] Bruijniks SJE, Lemmens LHJM, Hollon SD, Peeters FPML, Cuijpers P, Arntz A, Dingemanse P, Willems L, van Oppen P, Twisk JWR, van den Boogaard M, Spijker J, Bosmans J, Huibers MJH. The effects of once- versus twice-weekly sessions on psychotherapy outcomes in depressed patients. Br J Psychiatry. 2020 Apr;216(4):222-30. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.2019.265

[61] Smits HJH, Seelen-de Lang BL, Nijman HLI, Penterman EJM, Nieuwenhuis JG, Noorthoorn EO. Voorspellende waarde van lichte verstandelijke beperking en PTSS voor behandelresultaten van patiënten met ernstige psychiatrische aandoeningen [The predictive value of mild intellectual disability/ borderline intellectual functioning and ptsd for treatment results in severely mentally Ill patients]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2020 Jan 1;62(10):868-77.

[62] Van Oenen FJ. Het misverstand psychotherapie. Den Haag: Boom; 2019.

[63] Keijsers GPJ. Het grote psychotherapiedebat. Tijdschrift voor Gedragstherapie. 2014;2014(3):142-72. Available from: https://www.tijdschriftgedragstherapie.nl/inhoud/tijdschrift_artikel/TG-2014-3-2/Het-grote-psychotherapiedebat#vt1

[64] Boendermaker PM, Schippers ME, Schuling J. Men neme tien deelnemers en één moderator… Het recept voor het uitvoeren van focusgroeponderzoek. Tijdschrift voor Medisch Onderwijs. 2001;20(4):1-6. DOI: 10.1007/BF03056518

[65] Thalen M, Oorsouw WMWJ, Volkers KM, Taminiau EF, Embregts PJCM. Integrated Emotion-Oriented Care for Older People With ID: Defining and Understanding Intervention Components of a Person-Centered Approach. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities. 2021 Jan 9;18(3):178-86. DOI: 10.1111/jppi.12370

[66] Anderson GL. Can participatory action research (PAR) democratize research, knowledge, and schooling? Experiences from the global South and North. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 2017 Apr 7;30(5):427-31. DOI: 10.1080/09518398.2017.1303216

[67] Dedding C, Goedhart NS, Broerse JEW, Abma TA. Exploring the boundaries of “good” Participatory Action Research in times of increasing popularity: dealing with constraints in local policy for digital inclusion. Educational Action Research. 2020 Mar 20;29(1): 20-36. DOI: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1743733